Why States Should Ban Universal Basic Income Schemes

Key Findings

- Universal basic income programs discourage work and trap people in dependency.

- Guaranteed income programs are costing taxpayers millions.

- States can stop local universal basic income programs and keep a culture of work in their state.

Overview

Across the country, local governments are running universal basic income pilot programs in an effort to further expand the welfare state.1 Universal basic income provides individuals with recurring cash payments with no strings attached—on top of other welfare benefits.2 Unlike some other welfare programs, these payments have no eligibility requirements or limits on how the money may be used.3

A similar type of program referred to as guaranteed income involves regular cash payments to a targeted or small sample population only.4 Some guaranteed income programs are targeted at individuals under certain income levels or residents of a particular city.5 But the purpose of guaranteed income programs is to build the case for a truly universal basic income.6

Unsurprisingly, universal basic income programs have been proposed by socialist politicians for decades, both in the United States and abroad.7 These programs disincentivize work and promote increased dependency on government handouts, at the expense of individual responsibility. There are currently more than 70 active pilot programs, costing taxpayers millions of dollars.8 A growing number of states are unwittingly playing host to these socialist experiments and should take immediate action and ban universal basic income.

Universal basic income would stifle the economy and fundamentally destroy the American ideal of self-determination

Universal basic income programs are an expansion of welfare, which has been shown to decrease workforce participation.9 By providing generous benefits designed to replace income, universal basic income discourages individuals from working. In a large-scale study of these programs in Seattle and Denver, cash payments caused a reduction in the hours worked.10

Beyond universal basic income specifically, there is a clear relationship between increased welfare benefits and decreased workforce participation.11 For example, over the last two decades, Medicaid expansion has largely been driven by able-bodied, working-age adults, and workforce participation rates have plummeted as a result.12 When individuals receive housing assistance, both workforce participation and earnings fall.13

Far from reducing poverty, the expansion of welfare traps people in a cycle of government dependency, instead of self-sufficiency and economic advancement.14 The fact is that most able-bodied adults on welfare do not work all.15 Able-bodied adults who are disconnected from the workforce are more socially isolated, more likely to commit crimes, and much more likely to abuse drugs.16-17

The negative impacts go beyond the individual. The last thing the economy needs is yet another incentive for workers to stay home. Today, there are nearly nine million open jobs.18 There have been more job openings than unemployed workers to fill them since May of 2021.19 Unemployment rates have still not recovered from the pandemic, and there are close to 1.7 million Americans missing from the labor force compared to pre-pandemic participation rates.20 Reduced labor force participation stunts economic growth and productivity.21 A decline in workforce participation means that there is less economic growth and an increased dependency ratio.22 This means that more people are relying on welfare, fewer people are contributing to tax revenues, and the GDP suffers as a result.23

During the pandemic, the federal government turned unemployment insurance into a universal basic income-like payment by suspending work search requirements, and expanding payments to more than $600 per week, creating a long-term, no-strings-attached cash benefit.24 Staying home began paying better than work for millions of Americans, driving a labor shortage.25 Despite the increased payments ending, some sectors of the economy are still struggling to overcome the impact of this no-strings-attached government welfare expansion.26

When welfare benefits create a structure in which able-bodied adults are better off staying home than getting a job, everyone loses.

Cities across the country are implementing universal basic income programs

While universal basic income may seem more like an academic exercise than a serious policy proposal, the truth is that local jurisdictions are launching pilot programs across the country to try to build a case for universal welfare.

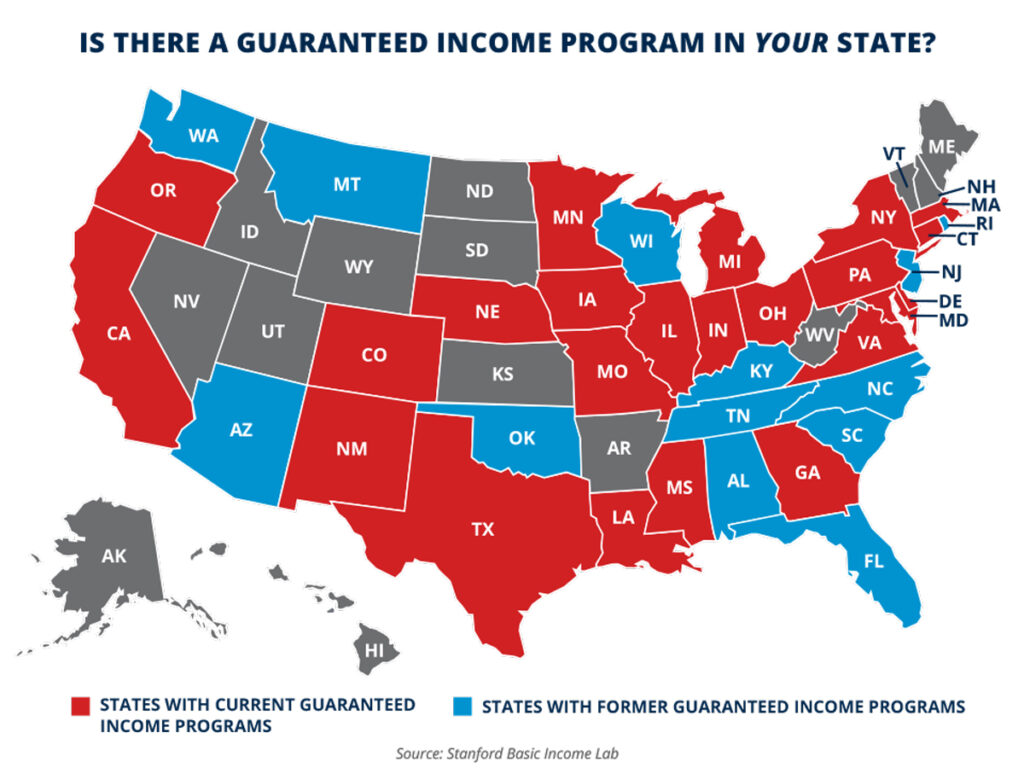

There have been more than 150 guaranteed income pilot programs across the country, with at least 70 currently active in 25 states.27 Local governments are using tax dollars to implement and support universal basic income programs independently of the state legislature.28 For example, five cities in Texas have piloted guaranteed income programs. Austin used a combination of taxpayer and private dollars to send $1,000 to a select group of individuals for 12 months.29 In 2023, the Austin City Council voted to approve a second round of the pilot program at a cost of $1.3 million in the city budget.30 In Louisiana, three cities have run guaranteed income pilot programs, including two in New Orleans.31

Altogether, a conservative estimate of spending on all of these universal basic income pilot programs both active and concluded comes to more than $2.35 billion.32 This figure includes private spending, as well as taxpayer dollars. 48 percent of the pilot programs have been funded at least partially with taxpayer dollars.33 Among those that are privately funded, many still use local government agencies and resources to distribute the payments and collect information about program participants.34

Taxpayer or privately funded, the end goal of these pilot programs is the same. These programs exist to provide a justification for a federally funded, nationwide universal basic income program.35 In California, it started with locally run, privately funded pilot programs in communities such as Stockton, which ran one of the nation’s first universal basic income pilot programs.36 This and similar programs were leveraged by advocates to create a case for universal basic income as a policy, and in 2021 a $35 million fund was created in the state budget to support pilot programs.37 In Cambridge, Massachusetts, what started as a privately funded pilot program is being expanded to all residents below the poverty line in the city, and is being funded through federal taxpayer dollars.38

125 mayors in 34 states and officials in 31 counties have publicly supported pilot programs.39 This list includes the Mayor of St. Louis, who recently announced that $5 million in federal taxpayer dollars would be used to fund a large universal basic income pilot in Missouri.40

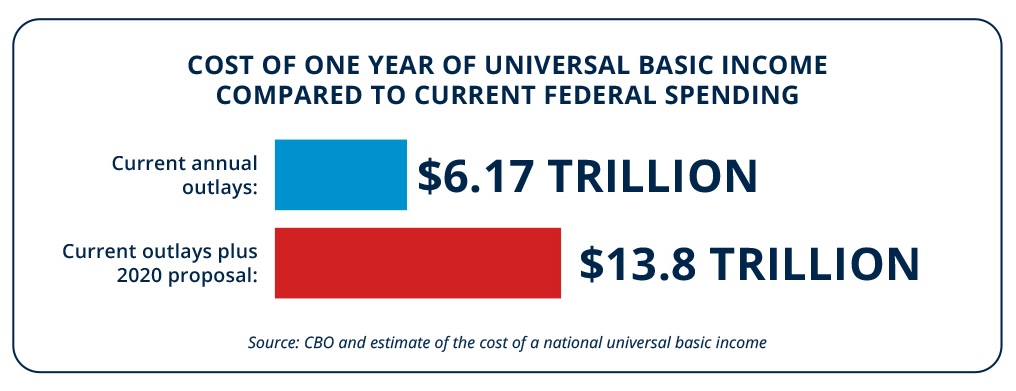

Proposals for universal basic income have been made at the federal level as well. In 2020, legislation was introduced that would have given almost every individual, including children, a $2,000 monthly payment for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic and three months following.41 While fortunately not enacted, this legislation would have cost taxpayers $590 billion each month, for all 42 months of the declared public health emergency, plus an additional three months.42 The total cost of this bill would have been almost $25 trillion.43 Just one year of providing $2,000 monthly to nearly all Americans would cost more than $7 trillion.44

More recently, legislation has been introduced that would require the federal government to provide $14,400 annually to adults, and $7,200 to children.45 Even this comparatively less extreme proposal puts the cost of a national universal basic income program at more than $3 trillion each year, and as high as $40 trillion over 10 years.46 Paying for just a single year of universal basic income under this proposal would balloon federal spending to more than $9 trillion, or require slashing half of current spending.47

Even eliminating all existing welfare programs, including food stamps, Medicaid, housing assistance, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and more would not come close to covering the cost of universal basic income.48

Advocates for these policies do not want to replace welfare, they want to enhance it. The legislation proposed to create a national universal basic income did not include cuts to any existing programs.49 In Nebraska, the state legislature even acted to exempt guaranteed income payments from local programs from being included as income for the purpose of calculating eligibility for welfare.50

States should ban universal basic income

Cities and local governments are facilitating universal basic income schemes across the country, and the impact of these programs is not confined to the city limits. States should pass legislation to prohibit guaranteed income and universal basic income pilot programs to ensure that their state remains economically strong. In 2023, Arkansas passed legislation to prevent a universal or guaranteed income program from being implemented or supported by local government in the state.51

Lawmakers can act to stop local governments from carrying out both taxpayer and privately funded programs to protect their state’s economy and ensure that work is encouraged. States do not need universal basic income pilot programs to know that the expansion of welfare in their state will hurt local employers, stifle economic growth, and trap people in a cycle of government dependency.

The Bottom Line: Universal basic income programs discourage work, are a drag on the economy, and should be banned by states.

Guaranteed income programs are being implemented in cities across the country, in red and blue states alike. The stated purpose of these programs, according to those who organize and fund them, is to build the case for universal welfare and government dependency. Universal basic income on a national scale would explode the deficit. It would also disincentivize work, worsen workforce shortages, and wreak economic havoc. States should guard against the explosion of the welfare state by prohibiting guaranteed income and universal basic income programs.

REFERENCES

1 Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, “End of year report 2023,” Mayors for a Guaranteed Income (2023), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60ae8e339f75051fd95f792e/t/65831bd96bb775626c8265e8/1703091162223/MGI_EOY+Report_2023_compressed+%281%29.pdf.

2 Maura Francese and Delphine Prady, “What is universal basic income?,” The International Monetary Fund (2018), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2018/12/what-is-universal-basic-income-basics.

3 Ibid.

4 California Department of Social Services, “Guaranteed income pilot program,” State of California (2022), https://www.cdss.ca.gov/inforesources/guaranteed-basic-income-projects.

5 Maura Francese and Delphine Prady, “What is universal basic income?,” The International Monetary Fund (2018), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2018/12/what-is-universal-basic-income-basics.

6 Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, “End of year report 2023,” Mayors for a Guaranteed Income (2023), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60ae8e339f75051fd95f792e/t/65831bd96bb775626c8265e8/1703091162223/MGI_EOY+Report_2023_compressed+%281%29.pdf.

7 Stanford University, “What is basic income?,” University of Stanford Basic Income Lab (2023), https://basicincome.stanford.edu/about/what-is-ubi/.

8 Stanford University, “Basic income lab,” Stanford University (2023), https://basicincome.stanford.edu/experiments-map/.

9 Christina King et al., “Reconnecting Americans to the benefits of work,” Joint Economic Committee (2021), https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/47745fcc-deba-418a-b05e-9fea2a32de71/connections-to-work.pdf.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Jonathan Bain, “The X factor: How skyrocketing Medicaid enrollment is driving down the labor force,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/research/x-factor-medicaid-enrollment-driving-down-labor-force/.

13 Christina King et al., “Reconnecting Americans to the benefits of work,” Joint Economic Committee (2021), https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/47745fcc-deba-418a-b05e-9fea2a32de71/connections-to-work.pdf.

14 Alli Fick, “How unemployment benefits have become the new welfare—And how to fix it,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/research/unemployment-benefits-the-new-welfare/.

15 Michael Greibrok, “Universal work requirements for welfare programs are a win for all involved,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/universal-work-requirements/.

16 Robert Doar, “Universal basic income would undermine the success of our safety net,” The George W Bush Institute (2018), https://www.bushcenter.org/catalyst/are-we-ready/doar-universal-basic-income.

17 Sam Adolphsen, “To help the truly needy, lawmakers should fix the welfare pit—Not the imaginary welfare ‘cliff’,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/lawmakers-should-fix-the-welfare-pit.

18 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Job openings and labor turnover study,” Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023), https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.nr0.htm.

19 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Job openings: Total nonfarm,” The Federal Reserve (2023), https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSJOL.

20 Stephanie Ferguson, “Understanding America’s labor shortage,” The US Chamber of Commerce (2023), https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/understanding-americas-labor-shortage.

21 Michael Dotsey et al., “Where is everybody? The shrinking labor force participation rate,” The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (2017), https://www.philadelphiafed.org/the-economy/macroeconomics/where-is-everybody-the-shrinking-labor-force-participation-rate.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Hayden Dublois and Kristi Stahr, “To restore confidence in unemployment systems states must pass commonsense reforms,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/restore-confidence-unemployment-states-pass-commonsense-reforms/.

25 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “How the new era of expanded welfare programs is keeping Americans from working,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/expanded-welfare-keeping-americans-from-working/.

26 Stephanie Ferguson, “Understanding America’s labor shortage,” U.S. Chamber of Commerce (2023), https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/understanding-americas-labor-shortage.

27 Stanford University, “Basic income lab,” Stanford University (2023), https://basicincome.stanford.edu/experiments-map/.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Blake DeVine, “Austin city council creates another guaranteed income program,” KXAN News (2023), https://www.kxan.com/news/austin-city-council-creates-another-guaranteed-income-program/.

31 Stanford University, “Basic income lab,” Stanford University (2023), https://basicincome.stanford.edu/experiments-map/.

32 Authors calculations based on data provided by Stanford University, “Basic income lab,” Stanford University (2023), https://basicincome.stanford.edu/experiments-map/.

33 Stanford University, “Basic income lab,” Stanford University (2023), https://basicincome.stanford.edu/experiments-map/.

34 Ibid.

35 Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, “End of year report 2023,” Mayors for a Guaranteed Income (2023), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60ae8e339f75051fd95f792e/t/65831bd96bb775626c8265e8/1703091162223/MGI_EOY+Report_2023_compressed+%281%29.pdf.

36 Cinnamon Janzer, “Guaranteed income initiatives are moving from pilots to policies,” Next City (2022), https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/guaranteed-income-initiatives-are-moving-from-pilots-to-policies.

37 Ibid.

38 Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, “End of year report 2023,” Mayors for a Guaranteed Income (2023), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60ae8e339f75051fd95f792e/t/65831bd96bb775626c8265e8/1703091162223/MGI_EOY+Report_2023_compressed+%281%29.pdf.

39 Ibid.

40 Kevin Held, “Applications open for St. Louis guaranteed basic income program,” Fox 2 Now (2023), https://fox2now.com/news/missouri/applications-open-for-st-louis-guaranteed-basic-income-program/.

41 Senator Kamala Harris, “S.3784 – Monthly Economic Crisis Support Act of 2020,” U.S. Senate (2020), https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3784/text?s=1&r=38.

42 Matt Weidinger, “Small-dollar demonstration projects can’t hide that a national guaranteed income program would cost trillions,” American Enterprise Institute (2023), https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/small-dollar-demonstration-projects-cant-hide-that-a-national-guaranteed-income-program-would-cost-trillions/.

43 Author’s calculations based on S.3784, the Monthly Economic Crisis Support Act of 2020.

44 Ibid.

45 Representative Ilhan Omar, “H.R.4895 – SUPPORT Act of 2021,” U.S. House of Representatives (2021), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4895?s=5&r=3.

46 Hilary Hoynes and Jesse Rothstein, “Universal basic income in the United States and advanced countries,” Annual Review of Economics (2019), https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-030237.

47 Congressional Budget Office, “The budget and economic outlook: 2023-2033,” The Congressional Budget Office (2023), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58848.

48 Hilary Hoynes and Jesse Rothstein, “Universal basic income in the United States and advanced countries,” Annual Review of Economics (2019), https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-030237.

49 Representative Ilhan Omar, “H.R.4895 – SUPPORT Act of 2021,” U.S. House of Representatives (2021), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4895?s=5&r=3.

50 Nebraska Legislature, “Legislative Bill 1081,” State of Nebraska (2016), https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=28837.

51 Arkansas General Assembly “House Bill 1681,” State of Arkansas (2023), https://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/Home/FTPDocument?path=%2FACTS%2F2023R%2FPublic%2FACT822.pdf.