To Help The Truly Needy, Lawmakers Should Fix The Welfare Pit—not The Imaginary Welfare “Cliff”

KEY FINDINGS

- People on welfare are not on the edge of a “cliff.” They are stuck in a dependency pit.

- Most able-bodied adults on welfare do not work at all.

- All major welfare programs already have transitional benefits built in.

- People are better off when they leave welfare.

- Universal work requirements are the solution to the welfare pit.

Overview

Enrollment and spending in welfare programs have grown dramatically in recent years, largely driven by increases in able-bodied adults receiving benefits.1 This increase in welfare dependency comes at a time when there are millions of open jobs.2 While welfare enrollment has grown, labor force participation has decreased dramatically, creating a generational workforce crisis.3

Misguided ideas among some state leaders and lawmakers in Washington, D.C. blame the dependency problem on an imaginary welfare “cliff.” It is telling that the proposed solutions almost always include expansions of welfare. The truth is that most welfare recipients are not near a cliff but are stuck deep in a pit of dependency. For those who escape the welfare pit, there are several transitional benefits to support their climb out of dependency and into a better life. True welfare reform that will lift millions out of the pit of dependency must include solid work requirements.

Most able-bodied adults are stuck deep in a welfare pit, not on the edge of an imaginary “cliff”

The welfare cliff theory espouses that most people on welfare are working but cannot grow their earnings for fear of losing out on taxpayer benefits. The idea is that people are intentionally holding themselves back from extra hours or pay raises because they will fall off the cliff with no support when they earn more income. But this is simply not true.4 In fact, most people on welfare are nowhere near the imaginary cliff, but instead are trapped in a pit of dependency.5

Data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) demonstrates this in the food stamp program. Just one percent of able-bodied adults on food stamps—191,000 adults nationally—are within even 10 percentage points of the eligibility limit.6 These individuals are a long way from losing eligibility, with room to earn thousands of dollars in additional income while remaining eligible for food stamps.7 For every able-bodied adult between 18 and 64 within even 10 points of the cutoff, there are 62 who are not working at all.8-9

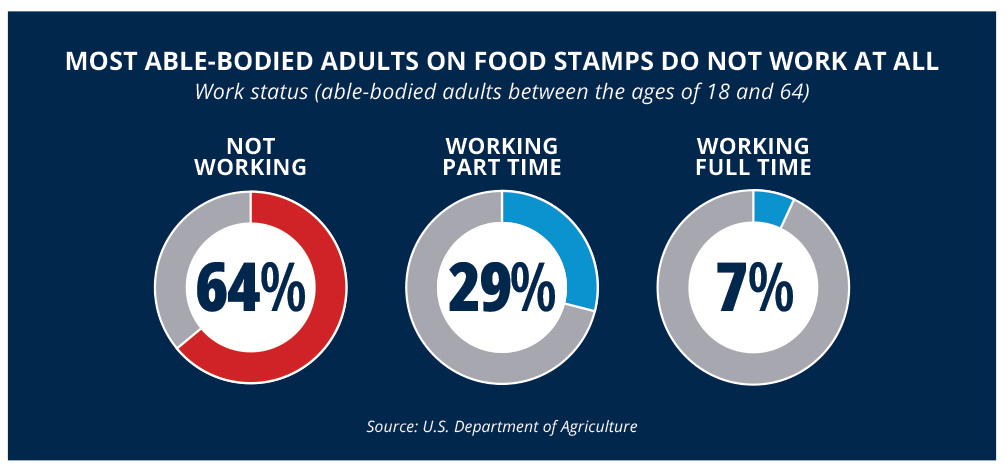

This is unsurprising as 64 percent of the able-bodied, childless adults between 18 and 64 on food stamps do not work at all.10 Only seven percent of all able-bodied adults ages 18 to 64 on food stamps work full time. Most adults on the program are not turning down a second job or extra hours to avoid a benefits cliff, but rather they are turning down any opportunity for income and the financial stability work provides.

This dynamic is the same in the Medicaid program, where able-bodied adults make up more than 40 percent of total enrollment, and more than half of all able-bodied adults on Medicaid are not working at all.11-12

All major welfare programs already have transitional benefits built in

Another myth is that welfare programs have a sudden drop-off instead of a sloping off-ramp. The facts show something completely different. Food stamps and Medicaid—the two largest welfare programs in the country—both have significant transitional benefits to gradually transition the recipient from welfare to self-sufficiency. And these transitional benefits have been expanded recently across the country.

FOOD STAMPS

The food stamp program has particularly strong transitional aspects. The monthly benefit amount for each household is calculated based largely on earned income.13 This means that as a recipient earns more income, there is a corresponding reduction in benefits. This creates a sloped ramp until the point at which the recipient would receive the minimum benefit amount.14 Then as earnings increase further, recipients would eventually earn above the allowed amount for eligibility and transition off the program.15 According to USDA, the benefit allotment, “is calculated by multiplying your household’s net monthly income by 0.3, and subtracting the result from the maximum monthly allotment for your household size.”16 As a result, there is a direct relationship between income and benefits—the opposite of a cliff.

For example, if a food stamp household with four individuals reported zero earned income, they would receive a monthly benefit of $939.17 As they earn more income, that same household may move closer to an average benefit, putting them roughly in the $450 dollar per month range.

However, if their household earned income increases and they near the earned income cap, which in most states is between 160 percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty level, they may receive closer to the minimum benefit of $29 per person per month.18-19 (200 percent of federal poverty is $60,000 annually for a family of four). Finally, when they exceed the threshold of earnings, they will fully transition into the workforce and off food stamps.

MEDICAID

Medicaid is often pointed to as the welfare program with the steeper cliff, if only because benefit amounts are not tied to income in the same way as the food stamp program. With Medicaid, someone who is eligible receives open-ended health benefits that vary with each recipient. The income threshold for Medicaid eligibility in most states is a household that earns under 133 percent of federal poverty level, or $39,900 for a family of four.20

But when someone earns over the limit, they are not suddenly left without coverage options. Further allaying concerns of believers in a welfare cliff, the most vulnerable are also the ones with the smoothest transition from Medicaid.

A recent action by Congress required states to provide a full 12 months of “continuous coverage” for all kids under the age of 19 on the program.21 This includes close to 40 million children, nearly half of total Medicaid enrollment nationwide.22 So, for the nearly 40 million kids on Medicaid, if they become eligible on July 1 and the very next month their household income rises above the maximum, they would still remain eligible for a full year. There is no cliff for any household with children on Medicaid.

The same is true for many pregnant women on Medicaid. Many states have income eligibility for pregnant women above twice the poverty level, and some states are above three times the federal poverty level, which is $90,000 for a family of four.23-24 And nearly half of all births are paid for by Medicaid.25 Yet in late 2022, Congress made permanent what used to be a temporary state option, providing a full year of Medicaid for postpartum mothers.26

Importantly, for any household that earns income above what is allowed by Medicaid, they would immediately become eligible for heavily subsidized—even free—private insurance plans on the federal health care exchange.27 State Medicaid agencies are even required to assist in the transition from Medicaid to those exchange plans.28 This coverage is provided up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level, or $120,000 for a family of four.29 The bottom line is that there is no cliff in Medicaid.

The food stamp and Medicaid programs are the nation’s largest welfare programs, representing more than 100 million people combined. Along with ignoring almost all assets held by applicants and recipients, the income eligibility threshold and benefits calculations in each program smooth any cliff that might be imagined by those who wish to expand the programs.

An earned dollar is more valuable than a welfare dollar

One of the main flaws in the welfare cliff theory is the claim that there is a penalty for leaving welfare. The claim is that if someone earns too much and leaves welfare, or “falls off the cliff” that they are worse off.30 They do not fall off a cliff, they become financially self-sufficient. This is a good thing.

There are many other significant benefits that an earned dollar provides that a welfare dollar does not. There is the basic dignity and value that work creates. Employment nurtures new social relationships that transcend the workspace.31 The opposite is true with welfare. Staying home and receiving benefits is socially isolating. Social capital is not abstract, it is very real and greatly impacts a person’s life.32

Welfare also hurts future employment opportunities as it is much easier for someone with a job to get a better job. Studies have shown that an application from an employed person is four times more likely to be answered than that of an unemployed person.33 This has also proven true in studies specific to welfare. In Florida, people who went from welfare into lower paying jobs, like fast food, quickly moved on to higher-wage jobs.34

There are major health benefits of working. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), “work is one of the best predictors of positive outcomes for individuals with Substance Use Disorder.”35 Among those employed, SAMHSA says they are more likely to have “lower rates of recurrence,” “higher rates of abstinence,” and “improvements in quality of life.”36 SAMHSA also notes that crime is reduced as there is “less criminal activity and fewer parole violations,” among those who are employed.

Single people may meet their future spouse at work.37 Kids see their parents going to work, which sets a positive example and can help break the cycle of dependency. Businesses can fill many of the nearly 10 million open jobs, boosting the economy.38

But perhaps most importantly, more than 97 percent of people who work full time are not in poverty.39 To help put people on the path to self-sufficiency, the best plan is to get people back to work by fixing the welfare pit.

Work requirements can help Americans escape the welfare pit

Work is a proven way to help people escape dependency, and work requirements are a proven way to motivate people to find work. Work requirements incentivize people to climb out of the welfare pit and onto the path to self-sufficiency. Study after study has shown this to be true.

In Maine, when work requirements were re-instated in 2014, thousands moved from welfare to work and saw their incomes more than double.40 Kansas enacted similar policies in their welfare programs with similar results. Kansas families that left welfare saw their incomes more than double and their wages more than covered the welfare benefits they left behind.41

In Missouri, those leaving welfare saw their incomes jump by 70 percent in just three months, and then double overall, leaving them better off financially than they were on welfare.42 Similar work requirements helped tens of thousands of Mississippians escape the welfare pit by going to work in more than 700 different industries, while doubling their incomes.43 In Florida, the welfare caseload among able-bodied adults without dependents dropped by 94 percent, with people going back to work in more than 1,100 industries.44

These examples of success across a diverse group of states show that individuals are better off financially when they leave welfare and go back to work. Politicians who want to reduce dependency should focus on transitioning people from welfare to work. The simplest way to do this is by passing broad universal work requirements.45

The Bottom Line: Policymakers should reject welfare expansions disguised as fixing a “cliff.” Instead, policymakers should help able-bodied adults get out of the welfare pit by instituting broad work requirements for welfare programs.

Congress and states should avoid falling into the trap of trying to solve the false problem of a welfare “cliff.” Most people on welfare are not on the edge of a cliff but are trapped deep in a welfare pit, not working at all.

Proposals to solve the supposed “cliff” always expand welfare, making the welfare pit wider and deeper. These new expansions are not needed because there are already significant transitional benefits built into all major welfare programs.

Leaving welfare should never be considered a fall off a cliff because a dollar earned at a job is much more valuable than a dollar received in welfare. A dollar earned at a job comes with significant gains in dignity, social capital, experience, and improved health outcomes. Instead, escaping welfare should be celebrated and those with the ability to incentivize this move should do so.

Congress and states should be focused on solving the welfare pit problem by building ramps up and out of the welfare pit through work. Work requirements for able-bodied adults on welfare have proven in state after state to be the best way to lift people out of dependency and into self-sufficiency.

REFERENCES

1 Michael Greibrok, “Universal work requirements for welfare programs are a win for all involved,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/universal-work-requirements.

2 Ibid.

3 Jonathan Bain, “The X factor: How skyrocketing Medicaid enrollment is driving down the labor force,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/research/x-factor-medicaid-enrollment-driving-down-labor-force.

4 Jonathan Ingram and Sam Adolphsen, “Three myths about the welfare cliff,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/three-myths-welfare-cliff.

5 Ibid.

6 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on household incomes among non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 64, income-to-poverty ratios among such households, and income eligibility levels for non-disabled adults in each state.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the number of non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 64 receiving food stamps between October 2019 and February 2020, disaggregated by work status. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Fiscal year 2020 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program quality control database,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://snapqcdata.net/sites/default/files/2022-12/qcfy2020_st.zip/.

11 Jonathan Ingram, “House-proposed work requirements would limit dependency, save taxpayer resources, and grow the economy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/house-proposed-work-requirements.

12 Victoria Eardley, “ObamaCare’s not working: How Medicaid expansion is fostering dependency,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/obamacares-not.working-how-medicaid-expansion-is-fostering-dependency.

13 7 CFR § 273.10 (2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CFR-2022-title7-vol4/CFR-2022-title7-vol4-sec273-10.

14 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP eligibility,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2021), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/recipient/eligibility.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Sasha Gersten-Paal, “SNAP – Fiscal year 2023 cost-of-living adjustments,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/fy-2023-cola.

18 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “HHS poverty guidelines for 2023,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines.

19 Sasha Gersten-Paal, “SNAP – Fiscal year 2023 cost-of-living adjustments,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-fy-2023-cola-adjustments.pdf#page=2/.

20 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “HHS poverty guidelines for 2023,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines.

21 H.R. 2617 (2022), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2617/text/.

22 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Who enrolls in Medicaid & CHIP?” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2023), https://www.medicaid.gov/state-overviews/scorecard/who-enrolls-medicaid-chip/index.html.

23 Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicaid and CHIP income eligibility limits for pregnant women as a percent of the Federal Poverty Level,” Kaiser Family Foundation (2023), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/medicaid-and-chip-income-eligibility-limits-for-pregnant-women-as-a-percent-of-the-federal-poverty-level/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D#note-4.

24 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “HHS poverty guidelines for 2023,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines.

25 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Who enrolls in Medicaid & CHIP?” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2023), https://www.medicaid.gov/state-overviews/scorecard/who-enrolls-medicaid-chip/index.html.

26 H.R. 2617 (2022), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2617/text/.

27 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Subsidized coverage,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2023), https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/subsidized-coverage.

28 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Unwinding and returning to regular operations after COVID-19,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2023), https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/unwinding-and-returning-regular-operations-after-covid-19/index.html.

29 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “HHS poverty guidelines for 2023,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines.

30 Erik Randolph, “Welfare cliffs exist—Concludes team of economists,” Georgia Center for Opportunity (2023), https://foropportunity.org/welfare-cliffs-exist-concludes-team-of-economists.

31 Zameena Mejia, “Why having friends at work is so crucial for your success,” CNBC (2018), https://www.cnbc.com/2018/03/29/why-having-friends-at-work-is-so-crucial-for-your-success.html.

32 Liz Mineo, “Good genes are nice, but joy is better,” The Harvard Gazette (2017), https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2017/04/over-nearly-80-years-harvard-study-has-been-showing-how-to-live-a-healthy-and-happy-life.

33 Corinne Purtill, “The biggest mistake people make when searching for a job is not acting like they already have one,” Quartz (2017), https://qz.com/955079/research-proves-its-easier-to-get-a-job-when-you-already-have-a-job.

34 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has-transformed-floridians-lives.

35 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Substance use disorders recovery with a focus on employment and education,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2021), https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/pep21-pl-guide-6.pdf.

36 Ibid.

37 Katharina Buchholz, “How couples met,” Statista (2020), https://www.statista.com/chart/20822/way-of-meeting-partner-heterosexual-us-couples.

38 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Job openings and labor turnover survey,” U.S. Department of Labor (2023), https://www.bls.gov/jlt.

39 Preston Cooper, “Sorry Bernie, few full-time workers live in poverty,” Manhattan Institute (2016), https://manhattan.institute/article/sorry-bernie-few-full-time-workers-live-in-poverty.

40 Josh Archambault, “New report proves Maine’s welfare reforms are working,” Forbes (2016), https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2016/05/19/new-report-proves-maines-welfare-reforms-are-working/?sh=43f641dd3f6a/.

41 Jonathan Ingram, “The power of work – How Kansas’ welfare reform is lifting Americans out of poverty,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2016), https://thefga.org/research/report-the-power-of-work-how-kansas-welfare-reform-is-lifting-americans-out-of-poverty.

42 Hayden Dublois et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements.

43 Jonathan Ingram, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement.

44 Jonathan Ingram, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has-transformed-floridians-lives.

45 Michael Greibrok, “Universal work requirements for welfare programs are a win for all involved,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/universal-work-requirements/.