West Virginia’s Medicaid Meltdown: How Medicaid Expansion Has Ravaged the Mountain State

Key Findings

- In 2014, West Virginia took the bait and expanded Medicaid.

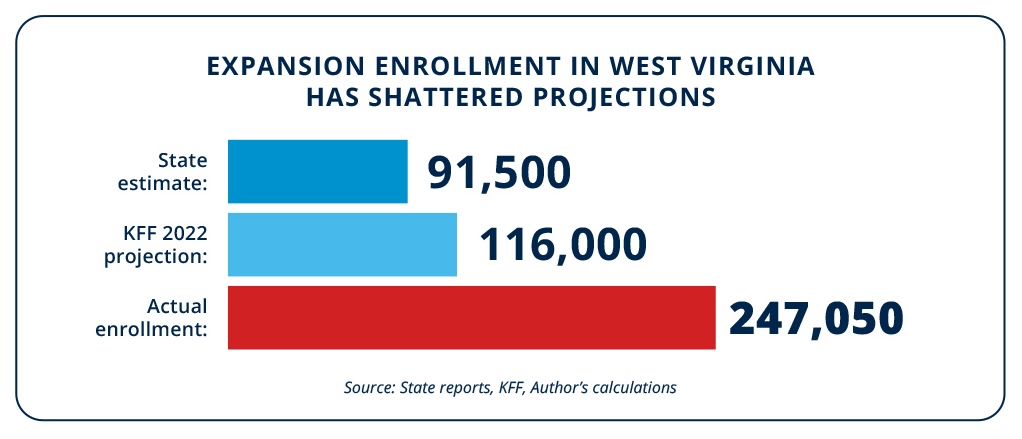

- Expansion enrollment has shattered projections with able-bodied adults enrolling at an unprecedented rate.

- As enrollment has continued to soar, spending has skyrocketed, and other budget priorities have suffered.

- Waste, fraud, and abuse have run rampant, and West Virginia is facing a Medicaid shortfall of $114 million in 2024.

- Lawmakers should implement program integrity measures to reverse course and protect the truly needy.

Overview

Under the Affordable Care Act—more commonly known as ObamaCare—states have the option to expand their Medicaid programs to include able-bodied adults.1 In 2014, West Virginia took the bait and expanded Medicaid.2 Unfortunately, the state fell victim to the false promises of expansion shortly thereafter.

Nearly a decade later, the ramifications are still being felt statewide and have been disastrous for West Virginians. Medicaid enrollment has skyrocketed, spending has soared, other budgetary priorities have suffered, and the truly needy have been left behind.3-5

Making matters worse, the state is facing a $114 million Medicaid shortfall that is looming over the budget.6 While the situation is dire, lawmakers in the Mountain State can take steps to address the problems permeating throughout the Medicaid program.

Enrollment has shattered projections

When West Virginia expanded Medicaid under then-Governor Earl Ray Tomblin, state officials projected that only 91,500 able-bodied adults would enroll through expansion.7 Another estimate—produced by the left-leaning Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF)—claimed that expansion enrollment would peak at 116,000 by 2022.8

Unfortunately, both estimates were inaccurate at best and misleading at worst, as program enrollment has skyrocketed. By the end of 2022, expansion enrollment reached nearly 245,000—outpacing projections by 93 percent and nearly double what the “experts” claimed.9-10

As able-bodied adults have flooded the Medicaid rolls, the program has ballooned in size. In December 2023, total enrollment sat just shy of 540,000—with nearly one in three West Virginians on Medicaid.11 Making matters worse, able-bodied adults made eligible through expansion accounted for 46 percent of total program enrollment by the end of 2023.12

As enrollment has shattered projections, the price tag for the state Medicaid program has soared, crowding out other budgetary priorities.

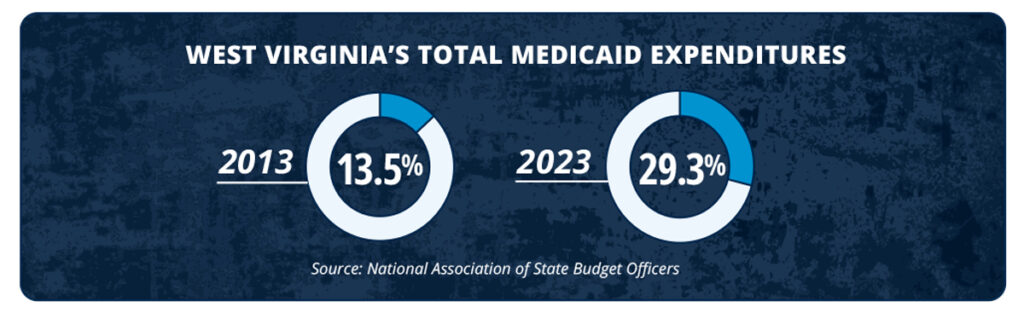

Medicaid is consuming the state budget

In 2000, West Virginia’s total Medicaid expenditures accounted for 21.5 percent of the state’s budget.13 But over the next 13 years, state lawmakers managed to lower this figure drastically. By 2013, the Medicaid program accounted for only 13.5 percent of the total budget—a decrease of more than half.14

In 2014, West Virginia chose to expand Medicaid, which was bad news for taxpayers, as the next decade would not be as kind. By 2023, Medicaid’s share of the budget accounted for nearly 30 percent of total state expenditures.15 Medicaid’s budget share grew by 117 percent from 2013 to 2023—more than doubling in that time frame alone.16-17

For taxpayers, the story only gets worse, as Medicaid spending in the Mountain State has skyrocketed in recent decades. In 2000, total Medicaid spending in West Virginia was just shy of $1.4 billion.18 But by 2013, spending would climb all the way to $3 billion—and eventually surpass $5 billion in 2023.19-20

Meanwhile, other budgetary priorities have suffered while Medicaid’s budget share has grown. K-12 education spending has been forced to plummet by 76 percent since 2000.21-22 And higher education has also taken a hit, with spending decreasing by 59 percent.23

As Medicaid has continued to grow, so have the problems with the program. Waste, fraud, and abuse have run rampant, and West Virginia is currently facing a Medicaid shortfall of $114 million.24

Waste, fraud, abuse, and a looming Medicaid shortfall

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, West Virginia was projected to have more than $155 million in improper Medicaid payments in 2023 alone.25 This should not be surprising, given the recent uptick in investigations and convictions from the state’s Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU).26

In 2019, the MFCU was transferred to Attorney General Patrick Morrisey’s office, where fraud referrals increased by nearly 58 percent between 2020 and 2022.27 The number of fraud and abuse or neglect cases referred for prosecution jumped by more than 42 percent during the same period.28

But despite the great strides made by the MFCU, West Virginia still faces a $114 million Medicaid shortfall that threatens the security of the state budget.29

The state claims that the shortfall is primarily driven by the loss of the enhanced Medicaid funding made available during the pandemic.30 While those pandemic-era policies were in place, West Virginia saw increased Medicaid enrollment—ineligible enrollees that could not be removed from the program.31 As the increased federal funding has phased out, states nationwide have started removing ineligible enrollees from their programs.32

Despite the unwinding process being underway, West Virginia has sustained significant damage. If the state is to regain control of its Medicaid program, changes are necessary.

Solutions to improve program integrity

While West Virginia’s Medicaid woes are worsening, there are still steps that state officials can take to reverse course and get the program back on the right track.

CROSS-CHECKING DATA

The first step to restoring program integrity is to implement regular data cross-checks to safeguard the program against ineligible enrollees. West Virginia already cross-checks Medicaid enrollment data with some databases, but not all. The state should cross-check all of the following: out-of-state EBT transactions, death records, incarceration records, and lottery records.33 The state should also cross-check against federal data, including wage records, new hire and child support data, and fleeing felon records.34 This information already exists, and the state utilizes some of these options, but officials should cross-check all available resources to fully protect taxpayers and the truly needy.

WORK REQUIREMENTS

When Arkansas implemented Medicaid work requirements, more than 14,000 able-bodied adults left the program due to increased incomes—with more than 9,000 able-bodied adults finding employment because of the work requirement.35 The Biden administration has made it clear that there will be no flexibility when it comes to Medicaid work requirements, but in the future, the option may be available—and West Virginia should move forward with work requirements when available.

ROLL BACK MEDICAID EXPANSION

The most effective way to safeguard the Medicaid program would be to unwind West Virginia’s Medicaid expansion. By rolling back expansion, hundreds of thousands of able-bodied adults would be removed from the state Medicaid program—freeing up resources for the truly needy and taxpayers alike.

The Bottom Line: West Virginia can still regain control of its Medicaid program.

Back in 2014, West Virginia took the bait and expanded Medicaid to an entirely new class of able-bodied adults.36 Since then, the effects have ravaged the state Medicaid program. Enrollment has shattered projections and spending has skyrocketed, Medicaid’s share of the budget is crowding out other priorities, and there is a looming $114 million Medicaid shortfall.37-39

Despite this, state officials can still remedy the situation by regaining control of the Medicaid program. By codifying program integrity measures, implementing work requirements, or even unwinding the existing expansion, program integrity can be salvaged and taxpayer resources can be freed up to serve the truly needy.

REFERENCES

1 Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission, “Overview of the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid,” Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (2023), https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/overview-of-the-affordable-care-act-and-medicaid.

2 Kaiser Family Foundation, “Status of state Medicaid expansion decisions: Interactive map,” Kaiser Family Foundation (2023), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map.

3 Department of Health and Human Resources, “West Virginia Medicaid managed care and fee for service monthly report 2023,” Department of Health and Human Resources (2023), https://dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Members/Managed%20Care/MCOreports/Documents/Managed%20Care%20Monthly%20Enrollment%20Report%20December%202023.pdf.

4 Brian Sigritz, “2023 State Expenditure Report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2023), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2023_State_Expenditure_Report-S.pdf.

5 Emily Rice, “Medicaid deficit looms,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting (2023), https://wvpublic.org/medicaid-deficit-looms.

6 Ibid.

7 Department of Health and Human Resources, “Expanding Medicaid: West Virginia’s best choice in a dynamic healthcare landscape,” Department of Health and Human Resources (2013), https://dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Medicaid%20Expansion/Documents/MEP.pptx.

8 John Holahan et al., “The cost and coverage implications of the ACA Medicaid expansion: National and state-by-state analysis,” Kaiser Family Foundation (2012), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/report/the-cost-and-coverage-implications.of-the.

9 Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicaid enrollment – New adult group,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2022), https://data.medicaid.gov/dataset/6c114b2c-cb83-559b-832f-4d8b06d6c1b9/data?conditions%5B0%5D%5Bresource%5D=t&conditions%5B0%5D%5Bproperty%5D=enrollment_month&conditions%5B0%5D%5Bvalue%5D%5B0%5D=12&conditions%5B0%5D%5Boperator%5D=in&conditions%5B1%5D%5Bresource%5D=t&conditions%5B1%5D%5Bproperty%5D=enrollment_year&conditions%5B1%5D%5Bvalue%5D=2022&conditions%5B1%5D%5Boperator%5D=%3D.

10 Department of Health and Human Resources, “West Virginia Medicaid managed care and fee for service monthly report 2022,” Department of Health and Human Resources (2022), https://dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Members/Managed%20Care/Documents/Reports/Managed%20Care%20Monthly%20Enrollment%20report%20December%202022.pdf.

11 Department of Health and Human Resources, “West Virginia Medicaid managed care and fee for service monthly report 2023,” Department of Health and Human Resources (2023), https://dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Members/Managed%20Care/MCOreports/Documents/Managed%20Care%20Monthly%20Enrollment%20Report%20December%202023.pdf.

12 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicaid enrollment – New adult group,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://data.medicaid.gov/dataset/6c114b2c-cb83-559b-832f-4d8b06d6c1b9/data?conditions%5B0%5D%5Bresource%5D=t&conditions%5B0%5D%5Bproperty%5D=enrollment_month&conditions%5B0%5D%5Bvalue%5D%5B0%5D=1&conditions%5B0%5D%5Bvalue%5D%5B1%5D=2&conditions%5B0%5D%5Bvalue%5D%5B2%5D=3&conditions%5B0%5D%5Boperator%5D=in&conditions%5B1%5D%5Bresource%5D=t&conditions%5B1%5D%5Bproperty%5D=enrollment_year&conditions%5B1%5D%5Bvalue%5D=2023&conditions%5B1%5D%5Boperator%5D=%3D.

13 Nick Samuels et al., “2000 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2001), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/NASBO%20StExpRep%202000.pdf.

14 Brian Sigritz et al., “2013 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2014), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/State%20Expenditure%20Report%20Fiscal%202012%202014%20S.pdf.

15 Brian Sigritz et al., “2023 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2023), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2023_State_Expenditure_Report-S.pdf.

16 Brian Sigritz et al., “2013 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2014), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/State%20Expenditure%20Report%20Fiscal%202012%202014%20S.pdf.

17 Brian Sigritz et al., “2023 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2023), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2023_State_Expenditure_Report-S.pdf.

18 Nick Samuels et al., “2000 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2001), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/NASBO%20StExpRep%202000.pdf.

19 Brian Sigritz et al., “2013 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2014), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/State%20Expenditure%20Report%20Fiscal%202012%202014%20S.pdf.

20 Brian Sigritz et al., “2023 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2023), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2023_State_Expenditure_Report-S.pdf.

21 Nick Samuels et al., “2000 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2001), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/NASBO%20StExpRep%202000.pdf.

22 Brian Sigritz et al., “2023 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2023), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2023_State_Expenditure_Report-S.pdf.

23 Ibid.

24 Emily Rice, “Medicaid deficit looms,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting (2023), https://wvpublic.org/medicaid-deficit-looms.

25 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2023 Medicaid and CHIP supplemental improper payment data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2023-medicaid-chip-supplemental-improper-payment-data.pdf.

26 Steven Adams, “W.Va. Medicaid Fraud Control Unit sees increased investigations, convictions under AG,” The Parkersburg News and Sentinel (2024), https://www.newsandsentinel.com/news/local-news/2023/09/w-va-medicaid-fraud-control-unit-sees-increased-investigations-convictions-under-ag.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Emily Rice, “Medicaid deficit looms,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting (2023), https://wvpublic.org/medicaid-deficit-looms.

30 Brad McElhinny, “Administration says it has a plan for the $114 million state gap on Medicaid spending,” MetroNews (2023), https://wvmetronews.com/2023/12/13/administration-says-it-has-a-plan-for-114-million-state-gap-on-medicaid-spending.

31 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “The Medicaid crisis is here: How Congressional handcuffs are causing Medicaid to implode,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/research/congressional-handcuffs-causing-medicaid-to-implode.

32 Michael Greibrok, “How Congress and states can rein in Biden bureaucrats while protecting taxpayers’ money and Medicaid program integrity,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/how-congress-states-can-rein-biden-bureaucrats.

33 Jonathan Bain, “Medicaid mismanagement: How states can restore integrity to the program while saving taxpayers billions,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/medicaid-mismanagement-states-can-restore-integrity.

34 Ibid.

35 Nic Horton and Victoria Eardley, “Arkansas’ Medicaid work requirement was working,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/arkansas-medicaid-work-requirement.

36 Kaiser Family Foundation, “Status of state Medicaid expansion decisions: Interactive map,” Kaiser Family Foundation (2023), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map.

37 Department of Health and Human Resources, “West Virginia Medicaid managed care and fee for service monthly report 2023,” Department of Health and Human Resources (2023), https://dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Members/Managed%20Care/MCOreports/Documents/Managed%20Care%20Monthly%20Enrollment%20Report%20December%202023.pdf.

38 Brian Sigritz, “2023 State Expenditure Report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2023), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2023_State_Expenditure_Report-S.pdf.

39 Emily Rice, “Medicaid deficit looms,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting (2023), https://wvpublic.org/medicaid-deficit-looms.