Medicaid Expansion Dramatically Increases Hospital Shortfalls …and Puts Their Futures at Risk

Key Findings

- Medicaid does not pay enough to cover hospitals’ costs, meaning hospitals need to make up for the shortfall by charging private payers more.

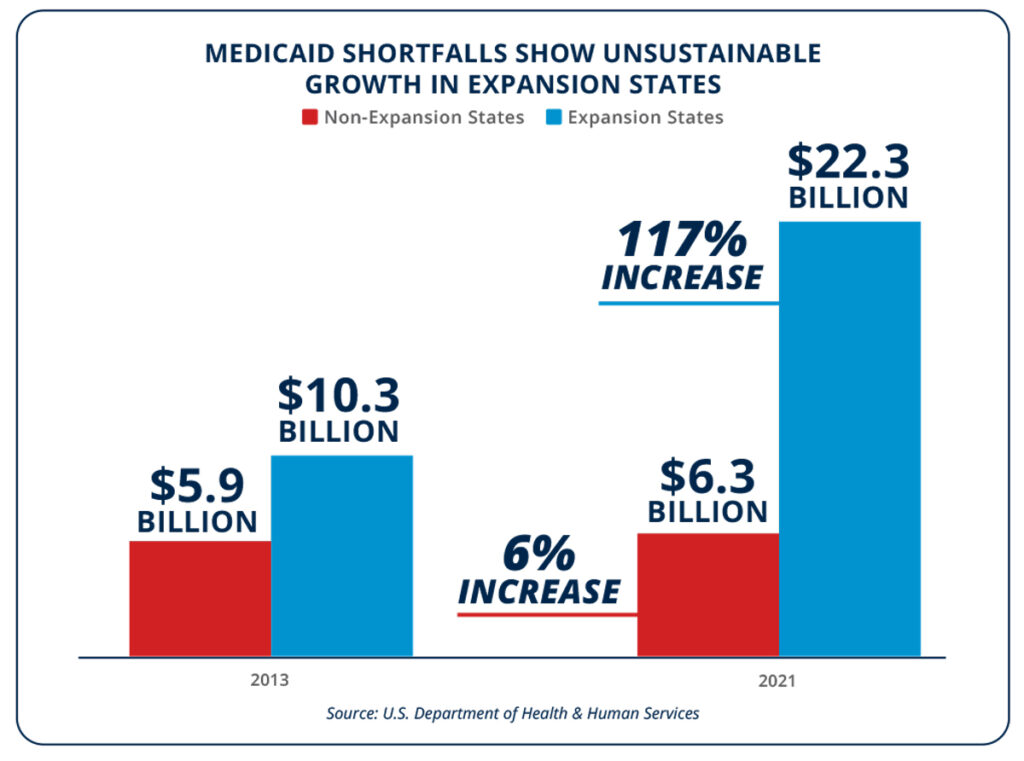

- In expansion states, hospitals’ Medicaid shortfalls have reached $22.3 billion, increasing by 117 percent since 2013.

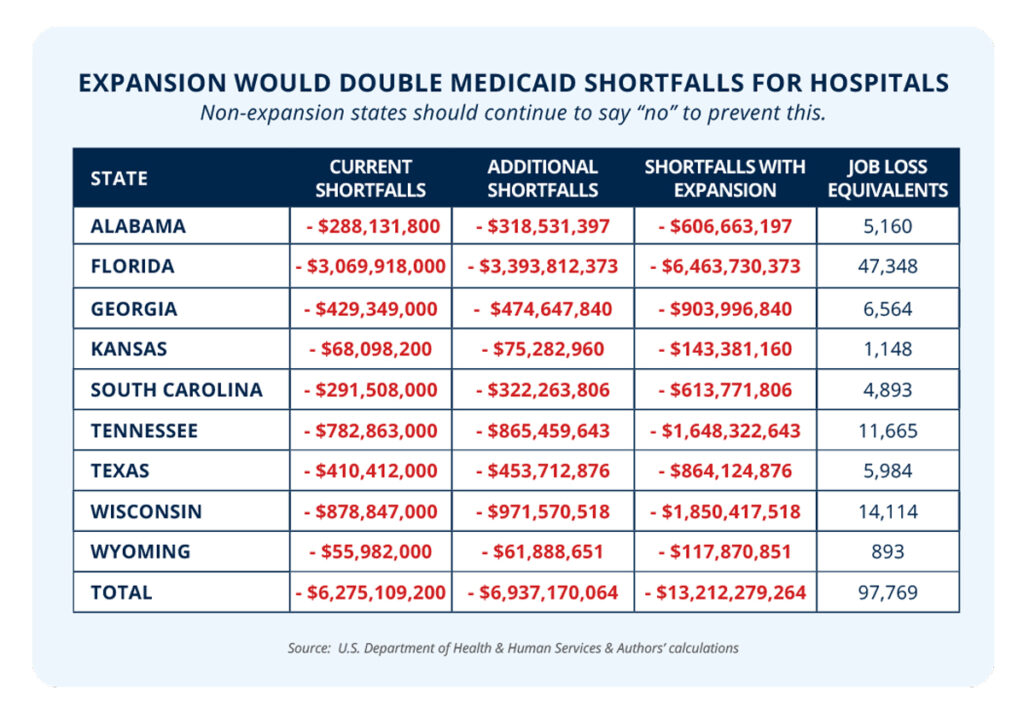

- If non-expansion states were to expand, their hospitals’ Medicaid shortfalls would more than double, from $6.3 billion to $13.2 billion.

- Non-expansion states should continue to say no to Medicaid expansion, and expansion states should work to roll it back.

Overview

Medicaid expansion ushered in through ObamaCare has led to program enrollment growth well beyond what was promised or projected.1 While proponents argue that expansion is a silver bullet to keep hospitals financially secure, this is simply not true.

Because Medicaid does not pay enough to cover the costs to hospitals to provide patient care, hospitals rely on private payers to make up for these losses.2

The lower payment rate and more Medicaid enrollees—especially those forced out of private coverage—mean increased Medicaid shortfalls, contributing to lower profit margins.3 This increases pressure on hospitals’ bottom lines, especially for rural hospitals where fewer patients make it more difficult to make up the shortfalls. The result is hospital closures in expansion states across the country. New data from the Department of Health and Human Services shows just how dire the situation is for hospitals in expansion states.

These issues would only be made worse if more states expanded Medicaid. Instead, states that have refused to expand Medicaid to cover more able-bodied adults should continue to stand strong. Likewise, states that have already expanded should work to roll it back.

Medicaid enrollment has skyrocketed since expansion

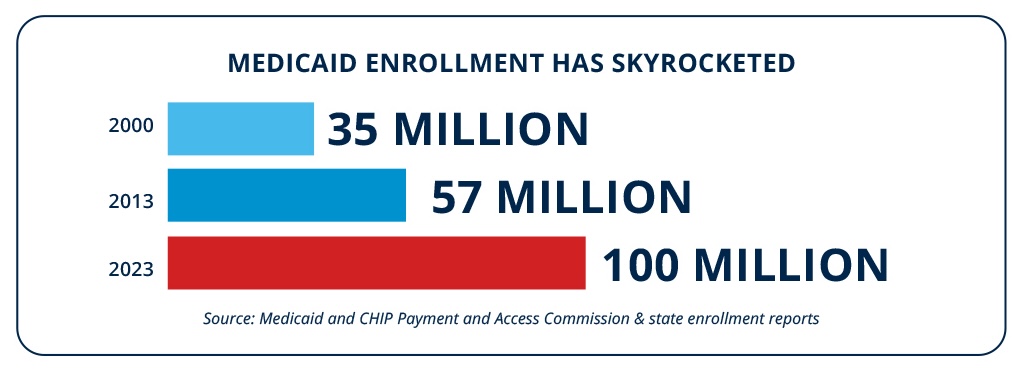

The Medicaid program was designed to help the truly needy, such as pregnant women, individuals with disabilities, and low-income children.4 Thirty-five million Americans enrolled in the program at the turn of the century, but enrollment ballooned to more than 100 million in 2023.5

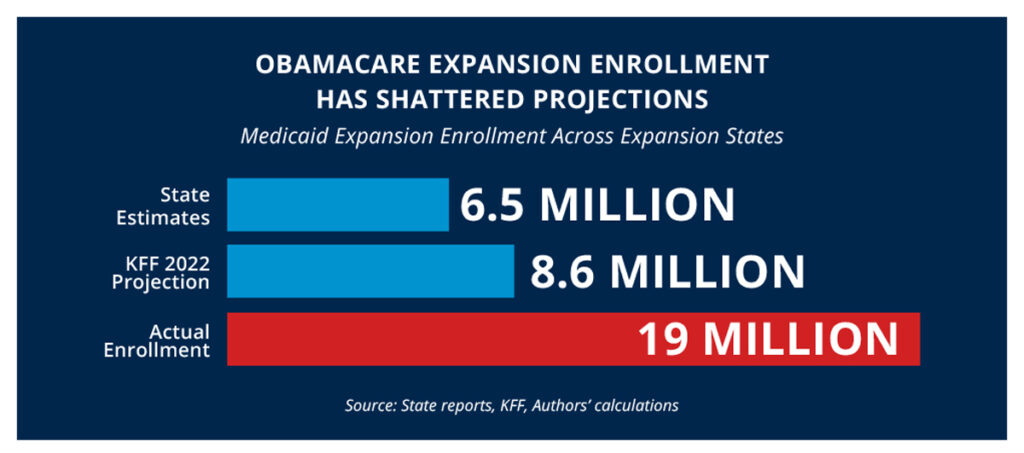

Much of this growth can be attributed to Medicaid expansion through ObamaCare, with enrollment sitting at roughly 57 million before expansion.6-7 This is because the number of able-bodied adults signing up for Medicaid has dwarfed projections.8 Expansion states claimed that fewer than seven million would enroll in the program through expansion, and third parties projected roughly nine million, but actual enrollment was at least 19 million.9

Since the payment rates are lower in Medicaid than in private pay, increased Medicaid enrollment has harmed hospital’s bottom lines.

A real-world comparison: expansion states versus non-expansion states

Not every state chose to expand Medicaid when given the chance beginning in 2014.10-11 This provides a real-life demonstration with nearly a decade of data, showing how covering so many able-bodied adults is affecting hospitals. This data can be invaluable for non-expansion states, as well as states that have expanded.

Hospital profits reveal the effects of Medicaid expansion

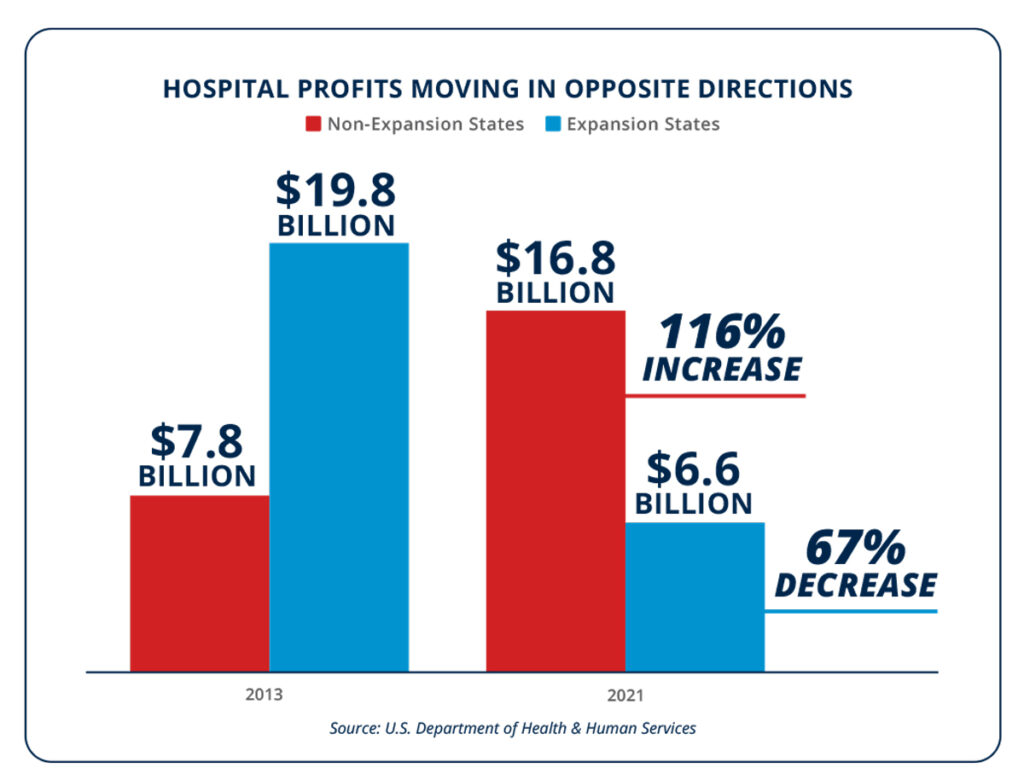

In terms of total hospital profits, expansion states and non-expansion states are moving in opposite directions.

Hospitals in expansion states saw their profits cut by two-thirds from 2013, before expansion, to 2021.12 Over that same timeframe, their profit margins were slashed from 6.2 percent to 1.4 percent.13 This means that for every dollar in revenue created by hospitals, less than two pennies are realized as profits. This is an average, so some hospitals failed to turn a profit at all.

Hospitals in non-expansion states on the other hand, have seen their profits more than double over this period.14 Their profit margins over this time have increased as well, with the margins increasing from 4.9 percent—less than expansion state hospitals at the time—to seven percent, or five times that of hospitals in expansion states.15

Hospitals in expansion states were in better financial shape before they expanded—but this has since flipped. It is not a case where hospitals in expansion states were facing financial difficulties before expansion that have simply continued. It is also not just a bad time for hospitals overall, because both profits and profit margins have increased for hospitals in non-expansion states.

The reason for this flip in financial stability in expansion states is that hospitals count on private payers to make up for the reduced payments provided by Medicaid. In non-expansion states, private payers averaged payments of 128 percent of hospital costs, whereas Medicaid averaged only 76 percent of costs.16

As a higher proportion of hospital services are billed to Medicaid because of expansion, there are not enough private payments to boost back profits. This is especially true in rural areas without a large patient base to draw from. Thankfully, as non-expansion states have resisted calls to expand, they have not suffered from this shift in payers from private insurance to Medicaid as expansion states have.

The story of hospitals’ profits and losses can largely be told by looking at Medicaid shortfalls.

Medicaid shortfalls are growing rapidly in expansion states

Because Medicaid does not pay enough to cover hospital costs, hospitals in most states have Medicaid shortfalls. That is, the difference between hospital payments from Medicaid and the cost of providing services to patients enrolled in Medicaid.

Since expansion states treat far more people on Medicaid, they face greater difficulty in overcoming the shortfalls. For instance, hospitals in non-expansion states receive 7.8 percent of their revenue from Medicaid, but this figure is nearly double—14.2 percent—for hospitals in expansion states.17

Since hospitals in both expansion and non-expansion states treat Medicaid patients, most all have shortfalls. The difference is the magnitude of the shortfalls.

What causes this enormous shortfall is easily explained. As more people in expansion states enroll in Medicaid, more hospital services get billed to Medicaid. As more hospital services are billed to Medicaid, the greater the shortfall becomes, since Medicaid does not pay hospitals enough to cover their costs.

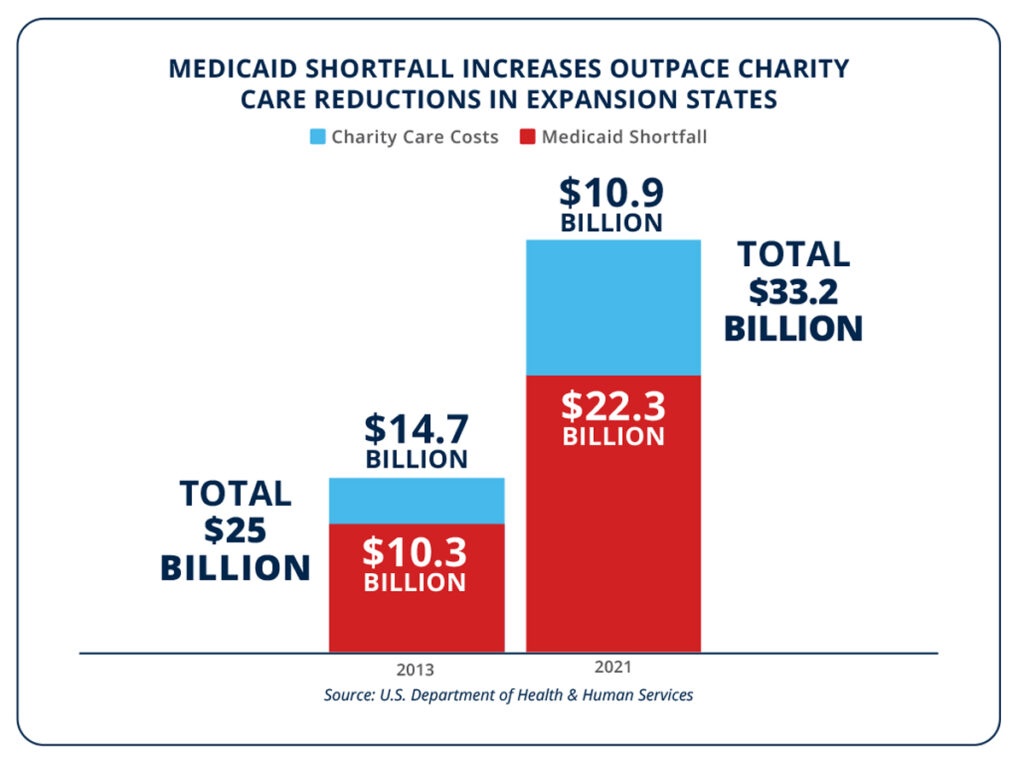

One argument for expansion has been that getting people enrolled in Medicaid will reduce the charity care needed to be provided by hospitals at no cost.22 But the savings hospitals in expansion states have realized in reduced charity care is overshadowed by the increased Medicaid shortfall. Since expansion, charity care costs have been reduced by less than $4 billion in expansion states—three times less than the shortfall increase.23 Saving a dollar to spend three is not a recipe for success, and these shortfalls are putting hospitals in a precarious financial position.

Additionally, charity care is not necessarily a net negative for hospitals. Most hospitals across the country operate as non-profits.24 By engaging in activities that benefit the communities they serve, including by providing charity care, enormous federal, state, and local tax breaks become available to the hospitals.25 For many hospitals, these tax breaks exceed the cost of providing charity care to the uninsured.26

Medicaid expansion has led to hospital financial struggles

Several hospitals, especially in rural areas, have recently closed and more are at risk of closing.27-28 Another argument made for Medicaid expansion is that it financially helps hospitals, especially rural hospitals.29 But the data from expansion and non-expansion states does not bear this out.

The more people that are shifted from private insurance to Medicaid, the higher the Medicaid shortfalls, and the lower hospital profits. Hospitals are learning that you cannot become solvent by providing more and more services below cost. This is a surefire way to bankruptcy, not solvency. Nobody would call offering goods or services below cost a successful long-term business plan.

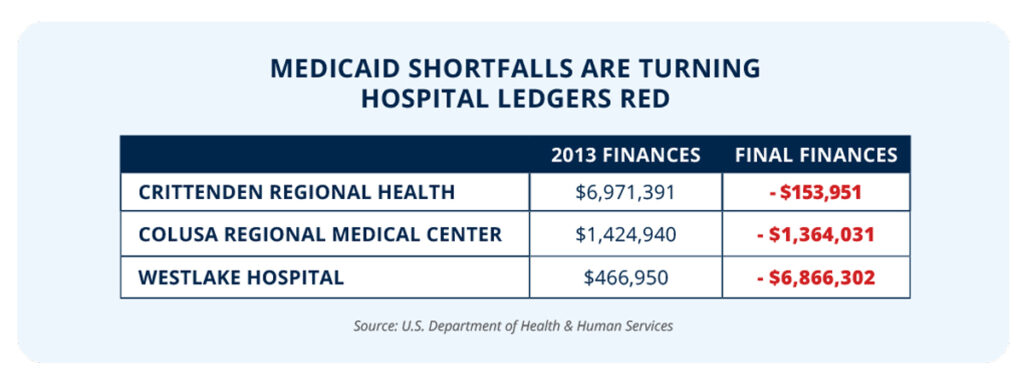

Reality has born this out, with a broad range of hospitals in expansion states closing across the country. In the South, Arkansas’s Crittenden Regional Health had a nearly $7 million surplus before expansion but soon closed after profits turned to losses.30 In the West, California’s Colusa Regional Medical Center also saw its profits turn to losses soon after expansion and was forced to close.31 In the Midwest, Illinois’s Westlake Hospital managed a surplus before expansion but by 2019 was operating at a nearly $7 million loss and was forced to close its doors.32

All of these saw their pre-expansion surpluses turn to losses by treating more able-bodied adults on Medicaid.

Further Medicaid expansion would only harm more hospitals

If more states chose to enroll able-bodied adults through Medicaid expansion instead of focusing on the truly needy, hospitals would feel the pain.

Medicaid expansion in the 10 remaining non-expansion states would push more than 3.6 million people from well-paying private insurance to Medicaid.33 This replacement of private payers with Medicaid payers would harm any hospital, but rural hospitals would be devastated by the switch. Likewise, taxpayers and hospitals would be forced to subsidize the health care of nearly 13 million additional able-bodied adults, crowding out funding for the truly needy.34 This would increase the Medicaid shortfall in these states and reduce hospital profits, possibly to the point of forcing more closures.

Expansion would more than double the Medicaid shortfalls for hospitals in those states, the equivalent of losing nearly 100,000 hospital jobs.35-36 As seen in expansion states, the reduction in charity costs would not come close to making up for the shortfalls resulting from the reduced Medicaid payment rates.

To prevent these harms, non-expansion states should continue to reject expansion. Likewise, states that have already expanded should work to roll it back.

The Bottom Line: Medicaid expansion does not help hospitals. Data shows it has been a huge negative for them. States that have refused expansion should continue to do so, while those that have expanded should seek to roll it back.

Enrollment of able-bodied adults through Medicaid expansion has shattered projections. Since the Medicaid payment rate is lower than a hospital’s cost of service, this has driven down hospital profits by increasing the Medicaid shortfall. This shortfall is contributing to hospital closures and increasing price pressures on countless others.

This evidence is clear that any further expansion would only harm the bottom lines of more hospitals by doubling the Medicaid shortfall in any state that chooses to expand. States that have not expanded should continue to avoid the Medicaid trap and those that have expanded should roll it back.

REFERENCES

1 Jonathan Bain, “How Millions of Americans will be kicked off private insurance if the remaining states expand Medicaid,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2024), https://thefga.org/research/how-millions-americans-kicked-off-private-insurance/.

2 American Hospital Association, “Underpayment by Medicare and Medicaid fact sheet,” American Hospital Association (2019), https://www.aha.org/system/files/2019-01/underpayment-by-medicare-medicaid-fact-sheet-jan-2019.pdf.

3 Jonathan Bain, “How millions of Americans will be kicked off private insurance if the remaining states expand Medicaid,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2024), https://thefga.org/research/how-millions-americans-kicked-off-private-insurance.

4 Ibid.

5 Jonathan Bain, “Busted budgets and skyrocketing enrollment: Why states should reject the false promises of Medicaid expansion,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/states-should-reject-false-promises-of-medicaid-expansion/.

6 Michael Greibrok, “Congress could boost economy by allowing Medicaid work requirements without bureaucratic intervention,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/congress-boost-economy-allowing-medicaid-work-requirements/.

7 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2013 CMS statistics,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2013), https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/cms-statistics-reference-booklet/downloads/cms_stats_2013_final.pdf.

8 Jonathan Bain, “Busted budgets and skyrocketing enrollment: Why states should reject the false promises of Medicaid expansion,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/states-should-reject-false-promises-of-medicaid-expansion/.

9 Ibid.

10 For purposes of this analysis, expansion states include those states that expanded Medicaid in January 2014: Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, North Dakota, New Jersey, New Mexico, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Washington, and West Virginia.

11 For purposes of this analysis, non-expansion states include: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Mississippi is excluded because it makes supplemental hospital payments through managed care organizations, funded by a tax on hospitals, making hospital-reported information less directly comparable.

12 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on hospital-level revenue and cost reports.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Gideon Lukens, “Uncompensated care costs fell in states that recently expanded Medicaid,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (2022), https://www.cbpp.org/blog/uncompensated-care-costs-fell-in-states-that-recently-expanded-medicaid.

23 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on hospital-level revenue and cost reports.

24 Julia James, “Nonprofit hospitals’ community benefit requirements,” Health Affairs (2016), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20160225.954803/.

25 Ibid.

26 Victoria Bailey, “Tax breaks exceeded charity care spending for nonprofit hospitals,” Revcycle Intelligence (2023), https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/tax-breaks-exceeded-charity-care-spending-for-nonprofit-hospitals.

27 Steven Ross Johnson, “States with the most rural hospital closures,” U.S. News & World Report (2023), https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/slideshows/states-with-the-most-rural-hospital-closures.

28 Dave Muoio, “’Unsustainable’ losses are forcing hospitals to make ‘heart-wrenching’ cuts and closures, leaders warn,” Fierce Healthcare (2022), https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/providers/unsustainable-losses-are-forcing-hospitals-make-heart-wrenching-cuts-and-closures-leaders.

29 Adam Searing, “Expanding Medicaid would help keep rural hospitals open in 14 non-expansion states,” Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy – Center for Children and Families (2020), https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2020/05/12/expanding-medicaid-would-help-keep-rural-hospitals-open-in-14-non-expansion-states/.

30 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on hospital-level revenue and cost reports.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Jonathan Bain, “How millions of Americans will be kicked off private insurance if the remaining states expand Medicaid,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2024), https://thefga.org/research/how-millions-americans-kicked-off-private-insurance/.

34 Jonathan Bain, “Busted budgets and skyrocketing enrollment: Why states should reject the false promises of Medicaid expansion,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/states-should-reject-false-promises-of-medicaid-expansion/.

35 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on hospital-level revenue and cost reports.

36 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Labor on average compensation of hospital employees.