States Must End Political and Religious Debanking

Key Findings

- Debanking is political and religious discrimination against certain groups or individuals.

- Financial institutions debank individuals, businesses, and non-profits when they abruptly deny access to services based on customers’ political or religious views.

- When individuals are debanked, financial institutions exploit the power they’ve obtained through government favoritism to cut ties with people with whom they disagree.

- Fortunately, states can take action to ensure financial institutions provide services free from unfair discrimination.

Overview

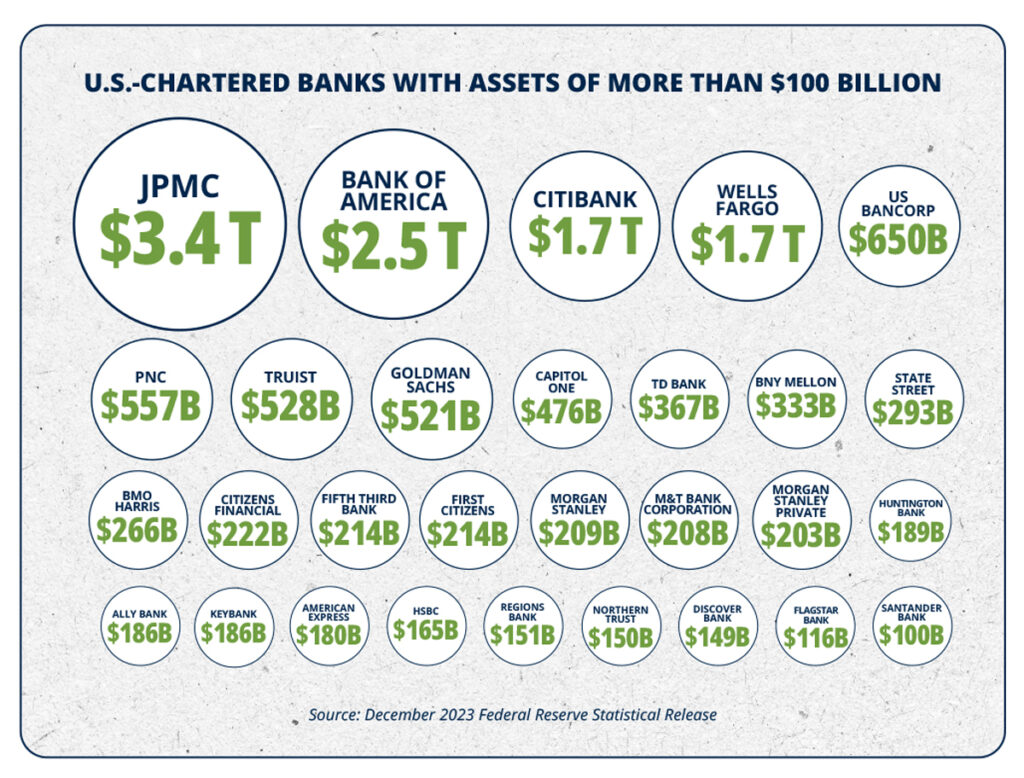

Debanking is an attempt by major financial institutions, those with assets of more than $100 billion, to close the accounts of organizations or individuals with whom they disagree, whether politically or religiously.1 This growing and disturbing trend denies individuals, businesses, and non-profits access to financial services.

Major financial institutions claim to be inclusive, but by aligning with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) criteria, they may neglect their fiduciary duties and discriminate against certain individuals and groups.2-3 Moreover, these large banks are intertwined with government, experiencing significant regulatory advantages granted by federal and state governments.4 These government-granted privileges are designed to facilitate commerce, but financial institutions are abusing these privileges by targeting individuals based on political and religious viewpoints.5

States should prohibit large financial institutions from denying individuals, businesses, and non-profits access to financial services based on their political, religious, or ideological viewpoints.

Debanking is political and religious discrimination against certain groups or individuals.

In recent years, banks have been sidelining particular individuals and groups through debanking. These individuals and groups go to access their accounts only to find that their accounts have been abruptly closed. If having a controversial political or religious viewpoint can justify a financial institution’s decision to debank someone, then that bank could wield boundless power over the everyday lives of Americans. Debanking is political and religious discrimination that seeks to pressure or silence those with whom they disagree.

Ironically, many of these banks push for inclusion and DEI quotas.6-7 But when it comes to their client base, they do not want diversity. Instead, banks pander to the Left. Banks should not be activists (on either side of the political spectrum).

A further indication of their ideological discrimination, financial institutions have demanded from those that they have debanked a list of their largest donors, political candidates they intend to support, and the criteria used to determine political support.8

Financial institutions debank individuals, businesses, and non-profits when they abruptly deny access to services based on customers’ political or religious views.

Major financial institutions have abruptly debanked individuals and groups, without explaining the reason behind their decision.

Bank of America, a company with consolidated assets of $2.5 trillion, suddenly canceled the account of Indigenous Advance Ministries, a Memphis-based Christian ministry worth less than $1 million, alleging that the ministry no longer aligned with the bank’s “risk tolerance.”9-12 In a similar example, Christian preacher and podcaster Lance Wallnau was debanked by Bank of America without meaningful explanation.13-14

JP Morgan Chase & Co. (JPMC) has engaged in a pattern of politically and ideologically charged debanking. In just two years, JPMC debanked groups such as The National Committee for Religious Freedom (NCRF), Arkansas Family Council, and Defense of Liberty.15 Individuals that JPMC debanked include Dr. Joseph Mercola, known for his controversial views on the COVID-19 vaccine.16

One group filed a shareholder proposal with JPMC in response to the bank’s religious and politically motivated debanking.17 The proposal requested an audit detailing JPMC’s policies and practices as they affect individuals’ civil rights.18 Although the request was ultimately denied, the proposal’s presence and attention in JPMC’s shareholder meeting show positive momentum for solutions for political debanking.19 Indeed, five key financial companies—Capital One Financial, Charles Schwab, JPMC, Mastercard, and Paypal— had related votes in the last year, thanks to those who are speaking out against discriminatory DEI practices.20

Unsurprisingly, JPMC’s Board of Directors claimed: “It is not our policy to debank people because of their political views or religious affiliation.”21 But when NCRF inquired about their account closure, JPMC reportedly told them their account would be reinstated as long as they provided NCRF’s major donor list, a list of political candidates they intended to support, and an explanation of NCRF’s criteria for determining its endorsements and support.22 Worse, in a letter to NCRF, JPMC falsely claimed they were required to ask these questions to prevent money laundering and terrorism financing.23-24

State attorneys general are worried about debanking. In a recent letter to major proxy voting advisory firms, 23 state attorneys general demanded sound proxy advice and transparency when addressing shareholder resolutions like the one mentioned above.25 The letter critiques both financial institutions like JPMC that violate customers’ civil liberties when they debank for political and religious reasons and proxy voting firms when they consistently vote against politically conservative proposals.

When individuals are debanked, financial institutions exploit the power they’ve obtained through government favoritism to cut ties with people with whom they disagree.

Banking is essential for modern life. To participate in today’s economy, one must have access to financial services, making banks quite powerful.

Because large financial institutions gatekeep capital, they can weaponize their power to exclude and blacklist those with whom they disagree. Combine debanking with the rising trend of de-platforming and the risks are immensely high for those who do not bow to leftist ideologies.26 And with the decline of cash and the growth of digital currency, there is growing potential for unbridled control.27-28

States seeking to prohibit debanking utilize the term “social credit score” to describe the rating system financial institutions use to unfairly discriminate against customers.29 Indeed, debanking is not unlike the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of a social credit score, which uses state-defined metrics to penalize bad social behavior. The official CCP goal for their system is to “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.”30 The CCP uses social media and internet data collection, digital surveillance, tip lines, and more to reward or punish individuals and businesses with a rating that affects many aspects of their lives, including their finances.31 Points are docked for numerous reasons, including traffic violations, anti-environmental behaviors, and spreading misinformation.32

Here in America, a former JPMC executive director and vice president claimed the bank uses “red dotting” to flag records internally to alert divisions to decline business for “reputational risk” reasons, including negative media coverage.33

Under the surface of debanking lies an obsession with control that flies in the face of self-governance and freedom. Large banks, made larger with the help of government, should not disregard the autonomy of individuals. This desire to use banks as a vehicle for control is not new. President Obama used reputational risk policies to pressure banks to cut ties with firearms dealers in Operation Choke Point.34 These banks side with the big-government Left in wanting to leave only politically charged options on the table.

To justify their actions, large financial institutions claim the moral high ground. In one example, Visa prohibits users from using one of its products, “in any manner that could be deemed…hateful.”35 Capital One prohibits transactions that “promote hate.”36 This is ripe for abuse as anyone not aligned with the company may simply be labeled as “hateful.” Fidelity Investments and Fidelity Charitable have been under pressure to refuse individuals and organizations deemed as “hate groups” by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a partisan leftist organization.37 SPLC lambasts groups such as ADF, Moms for Liberty, and the Family Research Council and designates them as hate groups.38 No group, in this case the far-Left SPLC, holds a moral barometer that can dictate which Americans have access to their money.

These actions are not justified. Though most businesses do have the right to refuse customers, banks are not like regular businesses. The government makes vitally important decisions for this sector. The consequential public privilege extended to banks distinguishes them from other businesses, and banks misuse their power when they debank certain customers over ideological disagreements.

Government and banks have a long history of working together, oftentimes for reasonable purposes. Special protections and regulations banks receive include:

- Government-issued charters, which banks must obtain to operate, raise the barrier to market entry and protect incumbents.39 Charters put the government in the driver’s seat, allowing it to grant or refuse charter applications. These banks also enjoy Federal Reserve-provided payment systems like FedACH to easily transfer money between chartered institutions.40

- Federal deposit insurance encumbers entrance into the market.41 The insurance is fully backed by the U.S. Government. It acts as a safety net and incentivizes risk-taking.

- Moreover, state and national bank lenders enjoy “most-favored lender” status, allowing them to lend nationwide with interest rates from their home state.42 Non-bank lenders do not enjoy this privilege and must obtain licenses in every state where they do business.43

- A similar scenario exists for money transmission licenses, which are authorized to national banks, waived for some state-chartered banks, but remain a costly and time-consuming burden for non-banks.44

- The government has at times provided direct assistance to particular banks, thus choosing winners and losers in the financial market.45

- Finally, although there are many more sources of government privilege to banks, the most egregious are direct government bailouts. Government has often stepped in to prevent banks’ failures, especially those deemed too big to fail.46

Political and religious debanking is government power wielded for private purposes.

Fortunately, states can take action to ensure financial institutions provide services free from unfair discrimination.

Few states have stepped up to prohibit debanking. With the exception of Florida, no state has made a substantial effort to hold large financial institutions accountable for political and religious discrimination.

Florida passed a law in May 2023 to combat debanking.47 Florida prohibits financial institutions from discriminating or canceling their services based on political opinions, speech, or affiliations, religious beliefs, exercise, or affiliations, and any action that considers a “social credit score” including lawful ownership of a firearm, failure to meet environmental or social governance standards, and more.48 Florida also requires financial institutions to attest their compliance on an annual basis.49

Separately, in West Virginia, State Treasurer Riley Moore banned five financial institutions—JPMC, BlackRock, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo—from contracting with the state over their attempt to maim the state’s fossil fuel industry.50 West Virginia could go a step further by broadly prohibiting large banks from using social credit scores. In Louisiana, State Treasurer John Schroder cut state ties with several banks because of the banks infringement on customers’ rights.51 Treasurer Schroder also divested Treasury funds from BlackRock to protect the state’s energy sector.52

The good news is that states can stop the political and religious discrimination of their residents. States should prohibit large financial institutions—banks with total assets of more than $100 billion, or payment processors with $10 billion or more per year in transactions—from using a social credit score to decline financial services to anyone. A social credit score is any analysis that evaluates a person’s exercise of religion or speech as protected by the First Amendment, or analysis of a person’s failure to adopt politically driven targets or social views.

States can permit the attorney general to investigate or seek remedies for any violations. Should a bank restrict or terminate service to a customer, the customer should have a mechanism to request why and receive a detailed explanation from the bank within 14 days.

The Bottom Line: States should prohibit large financial institutions from denying individuals, businesses, and non-profits access to financial services based on their religious, social, or political views.

Political and religious discrimination is hostile to a free society and has no place in America. Large financial institutions intertwined with government should be held accountable for unfair practices. The good news is that states can stop the political and religious discrimination of their residents. States should send a message to make clear that they will not tolerate the use of social credit scores and viewpoint discrimination. States can step up to put a stop to political and religious debanking.

REFERENCES

1 Sarah Coffey, “What is debanking? Political and religious discrimination by financial institutions,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/blog/what-is-debanking-political-and-religious-discrimination.

2 JPMorgan Chase & Co., “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” https://www.jpmorganchase.com/about/people-culture/diversity-and-inclusion#:~:text=OUR%20MISSION&text=%22Our%20business%20is%20stronger%20when,our%20people%20drive%20our%20success.

3 Bank of America, ” Being a diverse and inclusive workplace,” https://about.bankofamerica.com/en/working-here/diversity-inclusion#:~:text=Working%20together%20to%20advance%20racial,their%20whole%20selves%20to%20work.

4 Brian Knight and Trace Mitchell, “Private policies and public power: When banks act as regulators within a regime of privilege,” Social Science Research Network (2022), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3466854.

5 Ibid.

6 Zachary Halaschak, “Major bank to lower bonuses if diversity targets not met in initiative to triple minority staff,” Washington Examiner (2021), https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/policy/major-bank-to-lower-bonuses-if-diversity-targets-not-met-in-initiative-to-triple-minority-staff.

7 Lananh Nguyen, “Citigroup sets new diversity goals for workforce by 2025,” Reuters (2022), https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/citigroup-sets-new-diversity-goals-workforce-by-2025-2022-09-20.

8 Jordan Sattler, “The rise of religious debanking,” Alliance for Defending Freedom Ministry Alliance (2023), https://www.adfministryalliance.org/post/the-rise-of-religious-debanking#:~:text=Indigenous%20Advance%20Ministries&text=The%20bank%20had%20no%20problem,to%20partner%20with%20the%20ministry.

9 Federal Reserve Statistical Release, “Large Commercial Banks,” The Federal Reserve (2023), https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/lbr/current/.

10 ProPublica, “Indigenous Advance Ministries,” ProPublica (2023), https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/472790161.

11 Jamie Joseph, “Christian non-profit claims Bank of America ‘debanked’ them over religious discrimination,” New York Post (2023), https://nypost.com/2023/08/25/christian-non-profit-claims-bank-of-america-debanked.

12 Steve Happ, “Opinion: How Bank of America threatened our ministry to impoverished Ugandans,” The Sentinel (2023), https://republicsentinel.com/articles/opinion-how-bank-of-america-threatened-our-ministry-to-impoverished-ugandans.

13 Steve Warren, “Bank of America freeze ministry account of Lance Wallnau in latest case of banks canceling Christians,” The Christian Broadcasting Network (2023), https://www2.cbn.com/news/us/bank-america-freezes-ministry-account-lance-wallnau-latest-case-banks-canceling-christians.

14 Sam Brownback, “Vote yes: Proposal 10 – report on ensuring respect for civil liberties,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (2023), https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/19617/000197687823000002/PX14A6G.htm.

15 Treasurer John Murante et al., “Letter to J.P. Morgan Chase & Co,” The Wall Street Journal (2023), https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/documents/AGs-Letter-to-JP-Morgan-Chase.pdf.

16 GBNews, “‘HUGE inconvenience!’ Dr Joe Mercola opens up on being debanked over Covid views,” YouTube (2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUPeoJAbmPw.

17 Rule 14a-8 Review Team, “No action letter,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (2023), https://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/cf-noaction/14a-8/2023/bahnsenjpmorgan032123-14a8.pdf.

18 Ibid.

19 JPMorgan Chase & Co., “Annual meeting of shareholders proxy statement 2023,” JPMorgan Chase & Co. (2023), https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/investor-relations/documents/proxy-statement2023.pdf.

20 Heidi Welsh, “Anti-ESG shareholder proposals in 2023,” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance (2023), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2023/06/01/anti-esg-shareholder-proposals-in-2023/.

21 JPMorgan Chase & Co., “Annual meeting of shareholders proxy statement 2023,” JPMorgan Chase & Co. (2023), https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/investor-relations/documents/proxy-statement2023.pdf.

22 Jon Brown, “Chase Bank allegedly shutters bank account of religious freedom nonprofit, demands donor list,” Fox Business (2023), https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/chase-bank-allegedly-shutters-bank-account-religious-freedom-nonprofit-demands-donor-list.

23 Sam Brownback, “Vote yes: Proposal 10 – report on ensuring respect for civil liberties,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (2023), https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/19617/000197687823000002/PX14A6G.htm.

24 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Joint Fact Sheet on Bank Secrecy Act Due Diligence Requirements for Charities and Non-Profit Organizations,” (2020), https://www.fdic.gov/news/financial-institution-letters/2020/fil20106a.pdf.

25 Brenna Bird et al., “Debanking proxy advisor letter,” Iowa Department of Justice (2023), https://www.iowaattorneygeneral.gov/media/cms/Final_Debanking_Proxy_Advisor_Lette_738F6B3D5DF65.pdf.

26 The Free Speech Union, “PayPal deplatforms The Free Speech Union,” YouTube (2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2S7fZQvL0eE.

27 Emily Cubides and Shaun O’Brien, “2023 findings from the diary of consumer payment choice,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (2023), https://www.frbsf.org/cash/publications/fed-notes/2023/may/2023-findings-from-the-diary-of-consumer-payment-choice.

28 Anaya Kumar et al., “Central bank digital currency tracker,” Atlantic Council (2023), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/cbdctracker.

29 Laws of Florida, “Committee substitute for House Bill No. 3,” https://laws.flrules.org/2023/28.

30 N.S. Lyons, “The China convergence,” The Upheaval (2023), https://theupheaval.substack.com/p/the-china-convergence.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Morning Wire, “Bank cancels religious non-profit & new tax rules,” PodText (2022) see minute 4:14 – 5:24, https://podtext.ai/morning-wire/bank-cancels-religious-non-profit-new-tax-rules-12-26-22.

34 Frank Keating, “Operation choke point reveals true injustices of Obama’s Justice Department,” The Hill (2018), https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/politics/415478-operation-choke-point-reveals-true-injustices-of-obamas-justice.

35 Visa, “Visa solution terms of service,” Visa (2022), https://usa.visa.com/legal/checkout/terms-of-service.html.

36 Capital One, “Account disclosures,” Capital One (2023), https://www.capitalone.com/bank/disclosures/checking-accounts/online-checking-account/.

37 Michael P. Farris et al., “Philadelphia Statement on civil discourse and the strengthening of liberal democracy,” The Philly Statement (2022), https://thephillystatement.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Fidelity-Letter-with-Signatures-011822.pdf.

38 The Southern Poverty Law Center, “Frequently asked questions about hate and antigovernment groups,” Southern Poverty Law Center (2022), https://www.splcenter.org/20220216/frequently-asked-questions-about-hate-and-antigovernment-groups#hate%20group.

39 Brian Knight and Trace Mitchell, “Private policies and public power: When banks act as regulators within a regime of privilege,” Social Science Research Network (2022), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3466854.

40 The Federal Reserve, “FedAch Products & Services,” The Federal Reserve, https://www.frbservices.org/financial-services/ach.

41 Brian Knight and Trace Mitchell, “Private policies and public power: When banks act as regulators within a regime of privilege,” Social Science Research Network (2022), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3466854.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Lawrance L. Evans, Jr., “Government support for bank holding companies,” U.S. Government Accountability Office (2014), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-14-174t.pdf.

46 Brian Knight and Trace Mitchell, “Private policies and public power: When banks act as regulators within a regime of privilege,” Social Science Research Network (2022), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3466854.

47 Press Release, “Governor Ron DeSantis signs legislation to protect Floridians’ financial future & economic liberty,” Ron DeSantis 46th Governor of Florida (2023), https://www.flgov.com/2023/05/02/governor-ron-desantis-signs-legislation-to-protect-floridians-financial-future-economic-liberty.

48 Laws of Florida, “Committee substitute for House Bill No. 3,” https://laws.flrules.org/2023/28.

49 Ibid.

50 Press Release, “Breitbart: WV State Treasurer Riley Moore: U.S. bank has reversed its anti-energy lending policy — ‘This is how we win’,” Riley Moore for West Virginia (2022), https://www.mooreforwv.com/breitbart_wv_state_treasurer_riley_moore_u_s_bank_has_reversed_its_anti_energy_lending_policy_this_is_how_we_win.

51 Julie O’Donoghue, ” Louisiana bond commission pulls bank from refinancing deal over gun policy,” Louisiana Illuminator (2021), https://lailluminator.com/2021/11/18/louisiana-bond-commission-pulls-jpmorgan-from-refinancing-deal-over-banks-gun-policy/.

52 John M. Schroder, “Schroder protects Treasury funds from ESG by divesting $794M from BlackRock,” Louisiana Department of Treasury (2022), https://www.treasury.la.gov/_files/ugd/a4de8b_588fa93a5a9242009b177e54f556f4ce.pdf.