Abuse in Plain Sight: How Bureaucrats Are Misusing Food Stamp Exemptions to Hide Their Errors

Key Findings

- No-good-cause exemptions are widely used to circumvent work requirements.

- Bureaucrats are abusing no-good-cause exemptions to hide food stamp errors.

- In some states, up to 100 percent of no-good-cause exemptions are issued retroactively.

No-good-cause exemptions are widely used to circumvent work requirements

There are currently 41 million Americans trapped in the cycle of dependency on the food stamp program—all while nearly nine million jobs remain open.1-2 States should be looking for ways to help get the millions of able-bodied adults on food stamps back to work, but unfortunately, in many states, the opposite is happening. Bureaucrats use waivers and exemptions far too often to excuse countless able-bodied adults from having to comply with food stamp work requirements.

One of these mechanisms is “no-good-cause exemptions,” also known as “discretionary exemptions” or “eight percent exemptions.” States can use these exemptions to excuse up to eight percent of their able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) from work requirements for any reason whatsoever.3 No good cause is needed.

Roughly two-thirds of states use these exemptions with little to no accountability.4 And with a stockpile of millions of exemptions currently at states’ disposal, the opportunities for abuse are widespread.5 Additionally, these exemptions carry over from year to year if unused. For example, if a state does not exempt eight percent of its ABAWD population in a given year, it can exempt 16 percent the following year.6

While this may sound like a way for bureaucrats to “benevolently” excuse ABAWDs from food stamp work requirements, in many instances there is a much more sinister motivation behind the issuance of these exemptions.

Bureaucrats are abusing no-good-cause exemptions to hide food stamp errors

Unfortunately, there is no prohibition on states issuing no-good-cause exemptions after the fact. In other words, in addition to a state applying these exemptions to prevent an ABAWD from having to work, bureaucrats can also use exemptions after that ABAWD was already supposed to have returned from work.

Why would bureaucrats want to use these exemptions retroactively? Put simply, to cover up their own mistakes. Making a mistake and failing to assign an ABAWD to work would typically increase a state’s food stamp error rate. States that have an elevated error rate for two consecutive years are subject to monetary penalties by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.7 Therefore, in theory, states have an incentive to minimize their errors by avoiding them in the first place.

Retroactively issuing no-good-cause exemptions provides a workaround for doing a good job the first time. They do not just minimize errors—they cover them up entirely. A state can retroactively excuse an ABAWD from having to return to work if that state forgot to remove them from the food stamp program for non-compliance with a work requirement. As a result, the state avoids an error.

States have brazenly admitted to engaging in this type of conduct to shield their mistakes from the federal government in order to cover up their errors. For example, California openly refers to this practice as “overissuance/error protection,” noting that “percentage exemptions may be granted to individuals who were inadvertently issued CalFresh benefits after exhausting their three countable months and who did not satisfy the work requirement or qualify for an exemption in the month that the CalFresh benefits were issued.”8

It is unsurprising that certain states are engaging in this type of conduct as there is a long history of states artificially lowering their error rates by hiding mistakes and manipulating the data.9 Even the leftist Urban Institute notes that “regional respondents reported that a common use of discretionary exemptions is to cover erroneously awarded benefits paid to ABAWDs who have exceeded their countable months.”10

This practice is widespread as states across the country are using no-good-cause exemptions to artificially depress their error rates by retroactively covering up mistakes.

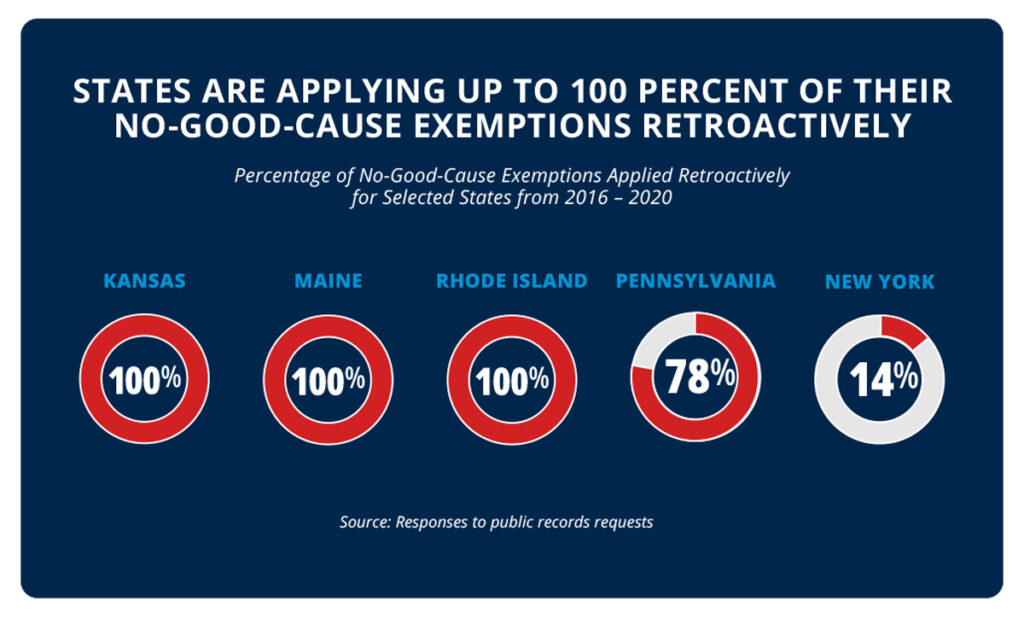

In some states, up to 100 percent of no-good-cause exemptions are issued retroactively

The Foundation for Government Accountability submitted public records requests to nearly two dozen states that are known to have used no-good-cause exemptions. While many states did not provide records, the handful that did turn over responsive materials present a troubling picture.

Across just these five states over a five-year period from 2016 to 2020, roughly 100,000 no-good-cause exemptions were issued retroactively.11 In these states—and undoubtably in others as well—bureaucrats are covering up their own mistakes to hide the true extent of their errors.12

This places downward pressure on food stamp error rates, which cannot be trusted to accurately reflect true errors in the program since states can and do manipulate the data after the fact with these exemptions.

The Bottom Line: Congress must rein in no-good-cause exemptions.

In 2023, as part of the debt ceiling deal, Congress reduced the percentage of no-good-cause-exemptions that can be applied by a state to its ABAWD population in a given year from 12 percent to eight percent.13 While this is a good start, much more can be done.

Congress should ban the use of these troublesome exemptions altogether. At the very least, Congress should prohibit the retroactive application of these exemptions to minimize their abuse.

In the absence of congressional action, states should own up to their mistakes in failing to assign ABAWDs to work. These mistakes should be reflected in their food stamp error rate, not covered up after the fact. States should endeavor to do better rather than concealing their blunders.

For the sake of accountability, policymakers must get no-good-cause exemptions under control and restore integrity to the food stamp program.

REFERENCES

1 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP: Monthly participation, households, benefits,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-4fymonthly-12.pdf.

2 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Job openings and labor turnover survey,” U.S. Department of Labor (2023), https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/JTS000000000000000JOL.

3 Alli Fick and Scott Centorino, “No good cause: How a food stamp loophole could become the next big battle in the war on work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/research/food-stamp-loophole-next-big-battle.

4 Ibid.

5 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP – Fiscal year (FY) 2024 allocations of discretionary exemptions for able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) – not adjusted for carryover,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/FY-2024-ABAWD-Discretionary-Exemptions-Memo-Not-Adjusted-For-Carryover.pdf.

6 Alli Fick and Scott Centorino, “No good cause: How a food stamp loophole could become the next big battle in the war on work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/research/food-stamp-loophole-next-big-battle.

7 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP quality control: How FNS helps protect taxpayer dollars,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://www.fns.usda.gov/blog/snap-quality-control-how-fns-helps-protects-taxpayer-dollars.

8 Response obtained from public records request submitted by the author.

9 Liesel Crocker, “Five ways that Congress can put a stop to food stamp fraud,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/five-ways-congress-can-stop-food-stamp-fraud.

10 Wheaton et al., “The impact of SNAP able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWD) time limit reinstatement in nine states,” Urban Institute (2021), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104451/the-impact-of-snap-able-bodied-adults-without-dependents-abawd-time-limit-reinstatement-in-nin_0.pdf.

11 Responses and data obtained from public records requests submitted by the author.

12 Ibid.

13 H.R.3746 of 2023.