How Congress Can Protect the Truly Needy and Restore Program Integrity to Food Stamps by Ending Broad-Based Categorical Eligibility

KEY FINDINGS

- States abuse loopholes to expand food stamp eligibility.

- 5.4 million food stamp recipients enrolled through broad-based categorical eligibility (BBCE) do not meet eligibility requirements.

- The BBCE loophole opens the door to waste, fraud, and abuse.

- Closing the BBCE loophole would save taxpayers nearly $112 billion.

Background

The food stamp program was designed to help the truly needy by supplementing money for food purchases.1-2 Federal law aims to preserve food stamps for the truly needy by limiting eligibility to individuals without sufficient financial resources. The federal food stamp statute purposefully sets income eligibility limits and requires that states check the financial assets of those applying for benefits.3

Asset tests are common in welfare programs. Yet the tests only apply to liquid assets—readily available money.4 The tests exclude homes, personal goods, retirement and pension plans, life insurance, one or more vehicles, and assets from enrollees receiving cash welfare from another program like supplemental security income.5

But states have used federal loopholes to essentially eliminate these requirements, expanding eligibility to millions who otherwise would not qualify for food stamps.

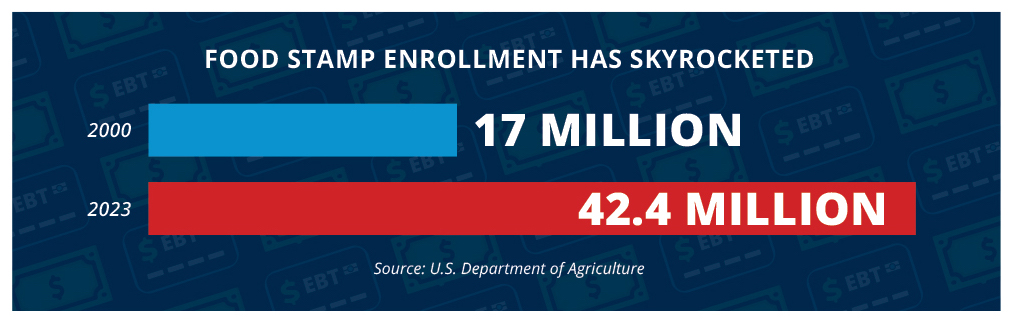

As a result, the food stamp program has exploded. The number of people on food stamps has more than doubled since 2000.6 The program’s cost to taxpayers has risen by nearly 600 percent.7

Unless Congress takes action to close these loopholes and restore program integrity, the situation will only get worse.

States abuse loopholes to expand food stamp eligibility

There are two general ways to qualify for food stamps. The first method uses federal eligibility requirements, including income and asset thresholds.8 The second method is categorical eligibility, where an individual or household can become eligible for food stamps based on their eligibility for another welfare program, like the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.

The stated purpose of categorical eligibility was to avoid duplication.9 It was not intended to expand eligibility. Yet welfare reforms adopted by the Clinton administration, then further expanded and pushed by the Obama administration, have created loopholes allowing states to expand categorical eligibility far beyond administrative simplification.10 States have expanded categorical eligibility to include receipt of a TANF non-cash “benefit,” eliminating the need for asset tests.11

Here’s how this works in practice: States receive money from the federal government for their cash welfare program in block grants. States then use that money to print welfare brochures and pamphlets or make referrals to a toll-free hotline providing information about the program. States deem the brochure or hotline a “benefit” and deliver it to food stamp applicants, making them “beneficiaries” of the state welfare program. These households are then “categorically eligible” for food stamps.

Worse yet, states can even grant eligibility to those who never receive the non-cash benefits, so long as they are “authorized to receive” the benefit.12 This is broad-based categorical eligibility. An individual may be deemed eligible without ever having received a TANF benefit.

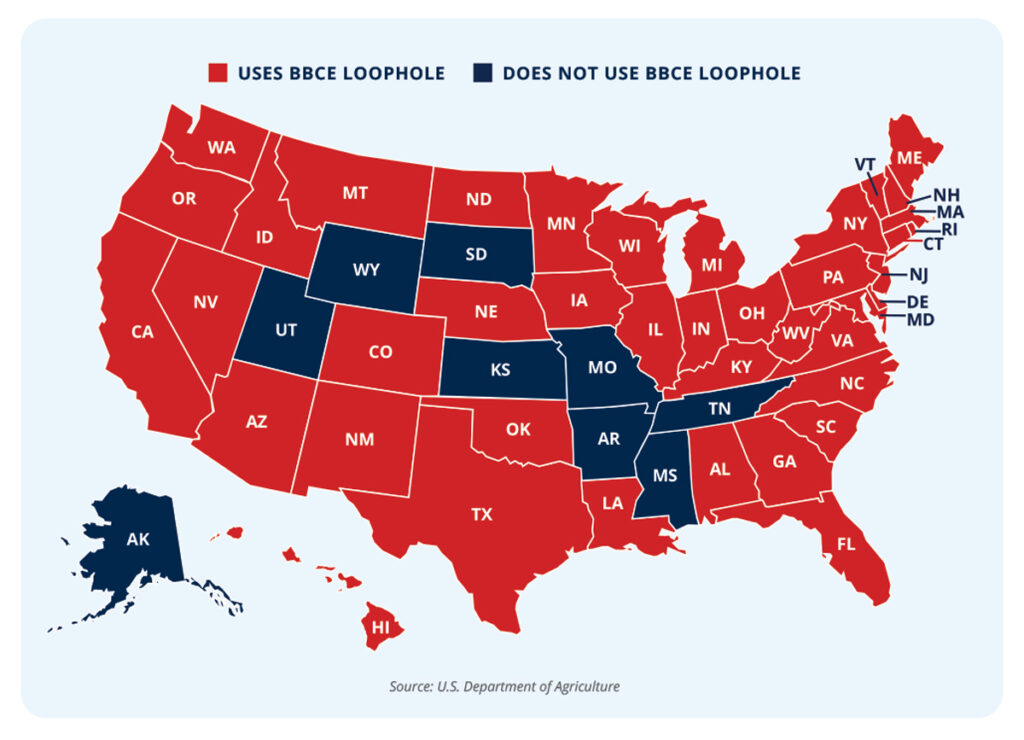

Forty-one states and Washington, D.C., now use the BBCE loophole, siphoning resources from the truly needy.13

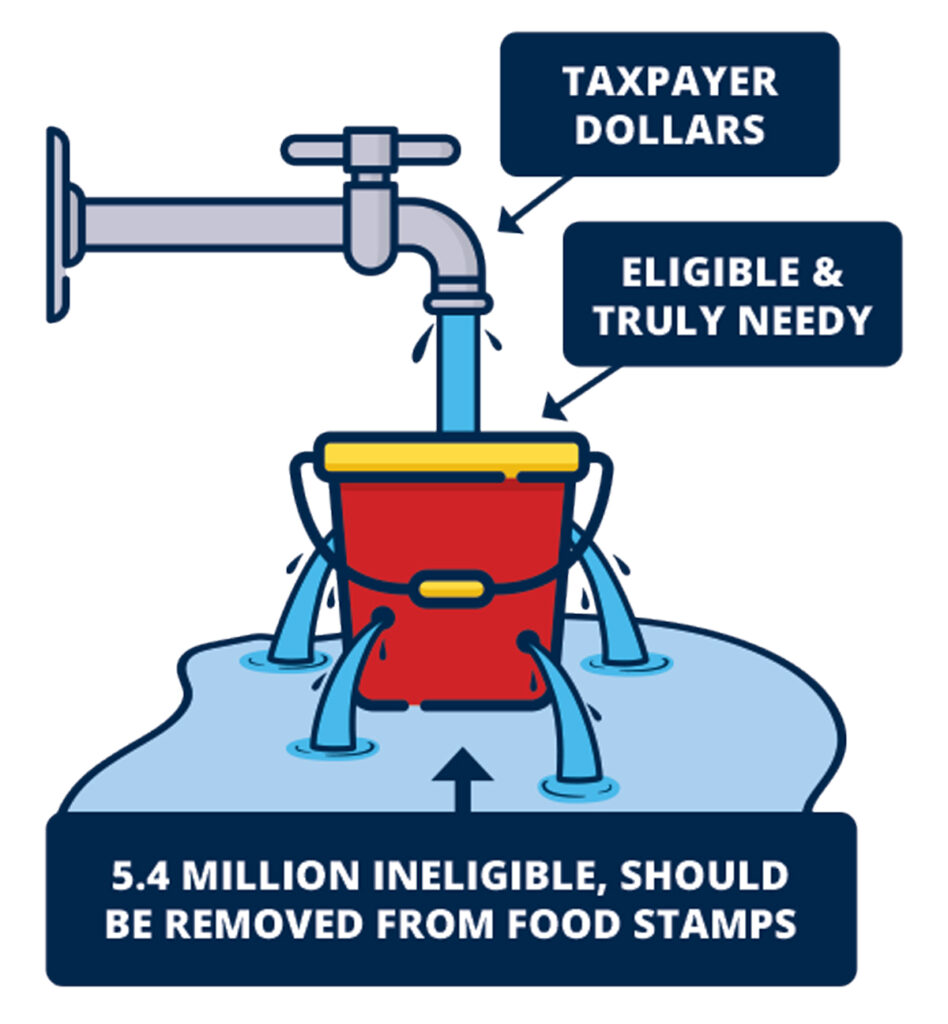

5.4 million food stamp recipients enrolled through BBCE do not meet eligibility requirements

More than 5.4 million enrollees on food stamps do not meet federal eligibility criteria, yet they have been enrolled through BBCE.14-21 Among those that do not meet eligibility requirements, more than 1.4 million individuals had incomes above the federal limit for their eligibility category, with the remainder having assets above federal limits.22 This diverts resources away from the truly needy.

Instead of focusing on the truly needy, food stamp benefits are going to millionaires. In Minnesota, millionaire Rob Undersander intentionally accepted food stamps to expose the system’s flaws.23 He collected $6,000 from the government in 19 months.24 Minnesota uses the BBCE loophole, allowing caseworkers to forgo asset checks.

But Mr. Undersander is not alone. An estimated one in five enrollees with assets above the federal asset limit have countable assets of $100,000 or more.25 And more than a third have countable assets worth at least $50,000.26

Food stamp dollars spent on millionaires and other ineligible enrollees siphon resources away from the truly needy.

The BBCE loophole opens the door to waste, fraud, and abuse

The food stamp program serves an important purpose. Yet with so many ineligible enrollees, the program is not working as intended. Limited taxpayer dollars should not be spent on ineligible enrollees, and BBCE opens the door for misuse. In 2012, for example, more than 15 million households never had their eligibility adequately assessed due to BBCE.27

Assuming eligibility can also lead to fraud. Households eligible under BBCE were nearly three times as likely to have payment errors than other households.28 Caseworkers reported a reduction in their level of verification using BBCE, as BBCE reduces their ability to check for inconsistencies.29

Waivers issued in response to the COVID-19 pandemic put program integrity for food stamps even further on the back burner, with improper payments not reported for several years.30-31

Congress defined eligibility rules purposefully to safeguard against misuse. State exploitation of the BBCE loophole renders the standard meaningless. The BBCE loophole must be closed to restore integrity to the food stamp program.

Closing the BBCE loophole would save taxpayers nearly $112 billion

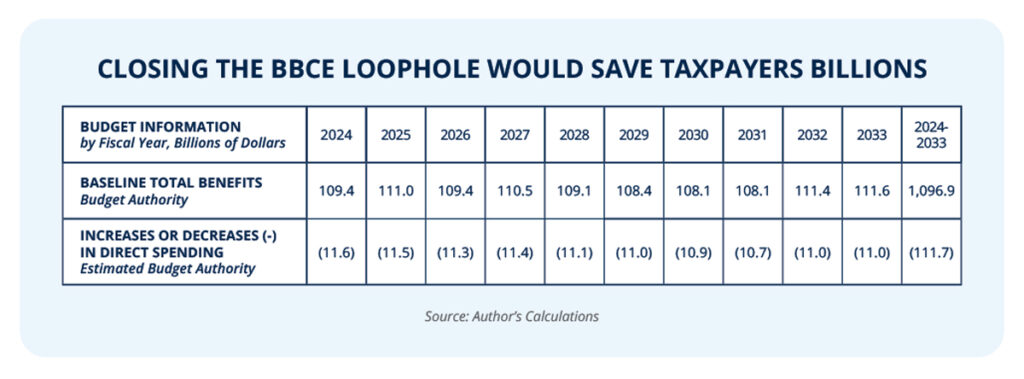

Food stamp spending is projected to exceed $1 trillion over the next decade.32 Closing the BBCE loophole would save nearly $112 billion during that time.33-36

Closing the BBCE loophole would deliver significant savings to taxpayers and safeguard the food stamp program for the truly needy.

The Bottom Line: Congress should close the BBCE loophole.

The federal food stamp statute intentionally created income and asset limits to preserve program resources for the truly needy, but the BBCE loophole allows states to willfully disregard them. The BBCE loophole is nothing more than a charade, allowing for an unintended expansion of the program.

In 2019, the U.S. Department of Agriculture under Secretary Sonny Perdue issued a proposed rule to close the BBCE loophole, which was later withdrawn by the Biden administration.37-38

Bureaucrats in the Biden administration show no signs of decelerating the push to expand welfare programs beyond their intended purpose, moving individuals away from self-sufficiency.39 Blue states, too, want to end asset tests and trap more people in dependency.40

Meanwhile, other states have introduced bills to protect the truly needy and close the BBCE loophole.41 Mississippi was successful in rolling back BBCE, saving taxpayers $117 million per year.42-43

Congress has an opportunity to follow the lead of states that have acted to roll back BBCE. If Congress steps up and closes the BBCE loophole, it can restore program integrity, protect the most vulnerable, and save taxpayers up to $112 billion over the next decade.

References

1 Michael Greibrok, “Universal work requirements for welfare programs are a win for all involved,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/universal-work-requirements.

2 Jessica Shahin, “Commemorating the history of SNAP: Looking back at the Food Stamp Act of 1964,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2014), https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2014/10/15/commemorating-history-snap-looking-back-food-stamp-act-1964.

3 7 U.S.C. § 2014(c), https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:7%20section:2014%20edition:prelim).

4 Randy A. Aussenberg, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): A Primer on Eligibility and Benefits,” Congressional Research Service (2022), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42505.

5 Ibid.

6 Food and Nutrition Service, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Costs,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-annualsummary-7.pdf.

7 Ibid.

8 7 U.S.C. § 2011, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021-title7-chap51-sec2011.pdf.

9 Food and Nutrition Service, “Letter to regions on categorical eligibility,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (1999), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/letter-regions-categorical-eligibility.

10 Jonathan Ingram, “Why closing the broad-based categorical eligibility loophole will not bust state budgets,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/why-closing-the-broad-based-categorical-eligibility-loophole-will-not-bust-state-budgets.

11 Randy A. Aussenberg and Gene Falk, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Categorical eligibility,” Congressional Research Service (2022), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R42054.pdf.

12 7 C.F.R. § 273.2, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2018-title7-vol4/pdf/CFR-2018-title7-vol4-sec273-2.pdf.

13 Food and Nutrition Service, “Broad-based categorical eligibility (BBCE),” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/broad-based-categorical-eligibility.

14 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by a proprietary microsimulation model that incorporates data on food stamp enrollment and expenditures in fiscal year 2020 disaggregated by age, disability status, eligibility category and income-to-poverty ratio, the distribution of income-eligible households by countable asset values in fiscal year 2006, broad-based categorical eligibility policies in effect in fiscal year 2023, participation rates of households and individuals made eligible under broad-based categorical eligibility policies, and federal asset thresholds in effect during fiscal year 2023.

15 Data on enrollment and expenditures between June 2020 and September 2020, disaggregated by age, disability status, eligibility category, and income-to-poverty ratio, was provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Fiscal year 2020 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program quality control database,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://snapqcdata.net/sites/default/files/2022.12/qcfy2020_st.zip.

16 Five states provided the U.S. Department of Agriculture with no data for the months of June 2020 through September 2020. For these states, the national average increase in enrollment among the disaggregated groups from the period between October 2019 and February 2020 to the period between June 2020 and September 2020 was applied to those five state states’ average enrollment among the disaggregated groups during the period October 2019 and February 2020.

17 The U.S. Department of Agriculture uses quality control data to produce demographic characteristics reports for food stamp enrollees. Fiscal year 2020 data is the most recent available for this purpose. However, overall enrollment has changed little since this data was produced. Between June 2020 and September 2020, overall food stamp enrollment averaged nearly 42.8 million. In April 2023, the most recent month that data is available, overall food stamp enrollment remained elevated at 41.9 million. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP monthly state participation and benefit summary,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource-files/SNAPZip69throughCurrent-4.zip.

18 Data on the distribution of individuals by countable asset holdings was derived from data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the distribution of income-eligible households by countable asset values in fiscal year 2006, the most recent data available. See, e.g., Karen Cunnyngham and James Ohls, “Simulated effects of changes to state and federal asset eligibility policies for the food stamp program,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2008), https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/85998/ccr-49.pdf.

19 Expenditure data was adjusted to reflect the increase in maximum allotments between fiscal years 2020 and 2023. Adjustments were made for each household based on geographic region and household size in the U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

20 Prior versions of this model were compared to the results produced by Mathematica Policy Research, the research contractor that produces policy microsimulation models for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The Foundation for Government Accountability’s proprietary microsimulation model produced nearly identical results as Mathematica Policy Research’s microsimulation models. See, e.g., Jonathan Ingram and Nic Horton, “Closing the door to food stamp fraud: How ending broad-based categorical eligibility can protect the truly needy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/closing-the-door-to-food-stamp-fraud-how-ending-broad-based-categorical-eligibility-can-protect-the-truly-needy.

21 The Foundation for Government Accountability’s proprietary microsimulation model produces similar results to those published by the Congressional Budget Office. In 2023, for example, this model estimated that the food stamp work requirements in the House-passed Limit Save Grow Act would save approximately $10 billion over a 10-year budget window. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that those provisions would save approximately $11 billion over that same budget window. See, e.g., Phillip L. Swagel, “CBO’s estimate of the budgetary effects of H.R. 2811, the Limit, Save, Grow Act of 2023,” Congressional Budget Office (2023), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-04/59102-Arrington-Letter_LSG%20Act_4-25-2023.pdf.

22 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by a proprietary microsimulation model estimating the enrollment effects of broad-based categorical eligibility, disaggregated by state and whether the household exceeded federal gross income limits, federal asset limits, or both.

23 Foundation for Government Accountability, “Minnesota millionaire Rob Undersander exposes food stamp loopholes,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/blog/rob-undersander-millionaire-food-stamps.

24 Don Davis, “Minnesota millionaire tells lawmakers he got food stamps to make a point,” TwinCities.com (2018), https://www.twincities.com/2018/04/11/minnesota-millionaire-tells-lawmakers-he-got-food-stamps-to-make-a-point.

25 Jonathan Ingram, “Closing the door to food stamp fraud: How ending broad-based categorical eligibility can protect the truly needy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/closing-the-door-to-food-stamp-fraud-how-ending-broad-based-categorical-eligibility-can-protect-the-truly-needy.

26 Ibid.

27 Office of Inspector General, “FNS quality control process for SNAP error rate,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2015), https://usdaoig.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/reports/2023-07/27601-0002-41.pdf.

28 Government Accountability Office, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, improved oversight of state eligibility needed,” U.S. Government Accountability Office (2012), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-12-670.pdf.

29 Ibid.

30 Office of Inspector General, “USDA’s compliance with improper payment requirements for fiscal year 2022,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://usdaoig.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/reports/2023-07/50024-0003-24finaldistribution.pdf.

31 Randy A. Aussenberg, et al., “USDA nutrition assistance programs: Response to the COVID-19 pandemic,” Congressional Research Service (2023), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46681.

32 Congressional Budget Office, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” Congressional Budget Office (2023), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-05/51312-2023-05-snap.pdf.

33 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by a proprietary microsimulation model estimating the enrollment and expenditure effects of eliminating broad-based categorical eligibility.

34 The number of enrollees ineligible under federal income and asset limits was determined by year and disaggregated by household type to reflect future increases in the federal asset limit.

35 Projected changes in total enrollment and in the maximum allotment determined by the Thrifty Food Plan were derived from data provided by the Congressional Budget Office. See, e.g., Congressional Budget Office, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” Congressional Budget Office (2023), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-05/51312-2023-05-snap.pdf.

36 Projected changes in asset limits were determined by projected inflation data provided by the Congressional Budget Office. See, e.g., Congressional Budget Office, “10-year economic projections,” Congressional Budget Office (2023), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-07/51135-2023-07-Economic-Projections.xlsx.

37 Food and Nutrition Service, “Proposed rule: Revision of categorical eligibility in the SNAP,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/fr-072419.

38 Ibid.

39 Philip L. Swagel, “Letter to Representative Jason Smith,” Congressional Budget Office (2022), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-06/58231-Smith.pdf.

40 Anna L. Nichols, “Whitmer signs bill ending asset test for food assistance in Michigan,” Michigan Advance (2023), https://michiganadvance.com/blog/whitmer-signs-bill-ending-asset-test-for-food-assistance-in-michigan.

41 “Rep. Ben Cline introduces No Welfare for the Wealthy Act,” Congressman Ben Cline (2023), https://cline.house.gov/media/press-releases/rep-ben-cline-introduces-no-welfare-wealthy-act.

42 Biannual Status Report, “Medicaid and Human Services Transparency and Fraud Prevention

Act,” Mississippi Department of Human Services (2022), https://www.mdhs.ms.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/HHSTP-Bi-Annual-Progress-Report-1-1-22-v.1-Final.pdf.

43 Jonathan Ingram, “Closing the door to food stamp fraud: How ending broad-based categorical eligibility can protect the truly needy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/closing-the-door-to-food-stamp-fraud-how-ending-broad-based-categorical-eligibility-can-protect-the-truly-needy.