Indexing Unemployment Set Kansas on Solid Ground

KEY FINDINGS

- INDIVIDUALS IN KANSAS CYCLED OFF UNEMPLOYMENT MORE QUICKLY.

- UNEMPLOYMENT TAXES WERE CUT BY MORE THAN HALF.

- KANSAS’S UNEMPLOYMENT TRUST FUND INCREASED FROM JUST UNDER $100 MILLION TO ALMOST $1 BILLION.

Overview

In 2013, Kansas reformed its unemployment program by indexing it to the unemployment rate.1 At the time, it lagged behind neighboring states (Colorado, Missouri, Nebraska, and Oklahoma) in key metrics like length of time on unemployment, employer tax rate on taxable wages, and trust fund amount.2 The state’s unemployment rate was also high coming out of the Great Recession at 5.8 percent.3

But unemployment indexing was exactly what Kansas needed. It improved in the same key metrics against its neighboring states.4 And by the end of 2019, Kansas had reduced its unemployment rate to 2.7 percent.5

Unemployment indexing is designed to be flexible. When unemployment is high, individuals have longer to look for work. But when the economy is strong, individuals cycle off unemployment more quickly. The policy ensures that when jobs are less abundant, workers have enough time to find their next job. But when employment is plentiful, it helps move unemployed workers toward

open jobs.

Indexing unemployment can put states on the right track by cycling workers off the program more quickly, reducing taxes, and bolstering trust funds.6-7 States should index unemployment to economic conditions to better position their programs and prepare for any future economic downturns.

Individuals cycled off unemployment more quickly

Kansas’s reform had many positive effects, including returning individuals to work much more quickly.

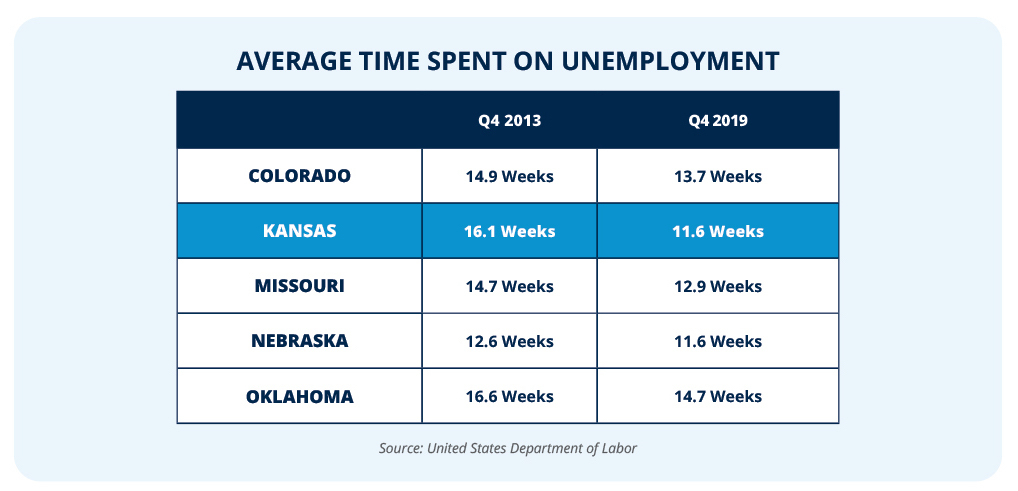

Before indexing, individuals collecting unemployment stayed on the program for an average of more than 16 weeks.8 This was among the worst rates in the region, with one state cycling their workers off unemployment more than three weeks quicker.9 As Kansans continued to collect unemployment, workers in nearby states were returning to work. An earlier return to work both strengthens a state’s economy and reduces the strain on a state’s unemployment trust fund.

Six years later, after unemployment indexing had taken hold, Kansas became a leader in moving workers off unemployment and back into the workforce.10 Kansans were cycling off the program after an average of only 11.6 weeks, more than four weeks quicker than pre-indexing.11

Kansas reduced its average stay on unemployment over this period by 28 percent, whereas the average in the region was 10 percent. This ability to get individuals back to work more quickly is key to helping boost the economy and put people on the path to self-sufficiency.

Unemployment taxes were cut by more than half

Unemployment indexing also paid dividends by reducing taxes paid by employers to support the unemployment insurance program. At the end of 2013, Kansas burdened its employers with an unemployment tax rate of 2.68 percent on taxable wages.12 This was the highest in the region at the time.

But by the end of 2019, Kansas reduced its unemployment tax rate to just 1.16 percent on taxable wages, a reduction of more than half.13 This can help businesses to lower prices, raise wages, or hire more workers. Employers may even be able to expand their business by increasing their products or services or expanding their reach.

Over these six years, neighboring states also reduced their unemployment tax rate on taxable wages, but not at the same pace as Kansas. At the end of 2019, the average rate for non-reform states sat well above Kansas’s at 1.77 percent.14 While small businesses in these states were forced to contribute more money to the unemployment system, Kansas entrepreneurs were able to reinvest in their businesses or pass savings on to their customers.

Kansas’s unemployment trust fund increased from just under $100 million to almost $1 billion

Before unemployment indexing, Kansas’s trust fund was in terrible shape. The fund sat at just under $100 million, well below the neighboring average of roughly $429 million.15 This left Kansas vulnerable in the case of an economic downturn.

After six years of indexing, Kansas’s trust fund was in a much better position, swelling to almost $1 billion.16 The state trust fund grew by more than 900 percent.17

Unemployment indexing put Kansas in a great position to help people during the next economic downturn. The boosted fund would also allow for further reductions to the unemployment tax.

The Bottom Line: Kansas set itself up for success by tying unemployment benefit duration to economic conditions, and other states should follow.

Unemployment indexing helped businesses and people across the Sunflower State. The policy positioned Kansas to provide a boost during the next downturn in the economy. Indexing improved Kansas’s ability to cycle workers off unemployment, reduced taxes on small businesses, and built up the trust fund.

Kansas would have realized even greater success if they had more closely followed states like North Carolina, Florida, and Alabama in establishing unemployment indexing.18-20 Each of these states’ indexing scales has a lower starting point and lower maximum than that of Kansas.21-24

Other states should set their citizens up for success by implementing unemployment indexing starting at 12 weeks and maxing out at 20 weeks. This will allow states to better prepare for the next economic downturn. By indexing unemployment to economic conditions, states can both reduce the tax burden on their small businesses and encourage individuals to find work when jobs are prevalent.

References

1 Kansas Sub HB 2105 of 2013, “Substitute for HB 2105 by Committee on Commerce, Labor and Economic Development,” Kansas State Legislature (2013), http://kslegislature.org/li_2014/b2013_14/measures/hb2105/.

2 Comparing Q4 2013 figures in average unemployment insurance duration past 12 months, the average tax rate on taxable wages past 12 months, and trust fund balance for Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

3 Kansas’s unemployment rate in Q1 2013 was 5.8 percent. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

4 Comparing Q4 2019 figures in average unemployment insurance duration past 12 months, the average tax rate on taxable wages past 12 months, and trust fund balance for Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

5 Kansas’s unemployment rate in Q4 2019 was 2.7 percent. See, e.g. Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

6 See Jonathan Ingram and Victory Ingram, “Opening opportunity: Tying unemployment benefits to economic conditions,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/paper/indexing-unemployment-benefits-economic-conditions/.

7 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “How indexing unemployment can restore state trust funds, cut taxes, and grow the workforce in the wake of COVID-19,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/indexing-unemployment-in-the-wake-of-covid19/.

8 The average duration of unemployment insurance for the past 12 months in Kansas in Q4 2013 was 16.1 weeks. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

9 In Q4 2013, Kansas’s average duration of unemployment insurance for the past 12 months was 16.1 weeks. This was more than peer states Colorado (14.9 weeks), Missouri (14.7 weeks), and Nebraska (12.6 weeks) and just a half week better than Oklahoma (16.6 weeks). See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp,

10 In Q4 2019, Kansas’s 11.6 weeks average duration of unemployment insurance for the past 12 months was equal or lower than Colorado’s (13.7 weeks), Missouri’s (12.9 weeks), Nebraska’s (11.6 weeks), and Oklahoma’s (14.7 weeks). See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

11 In Q4 2019, Kansas’s average duration of unemployment insurance for the past 12 months was 11.6 weeks, improving on the 16.1 weeks from Q4 2013. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

12 The average tax rate on taxable wages for the past 12 months in Kansas for Q4 2013 was 2.68 percent. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

13 In Q4 2019, Kansas’s average tax rate on taxable wages for the past 12 months was 1.16 percent, less than half the 2.68 percent from Q4 2013. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

14 In Q4 2019, the average tax rate on taxable wages for the past 12 months after removing reform states Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, and North Carolina was 1.7651%. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

15 In Q4 2013, Kansas’s trust fund sat at $99,480,000, the four peer states averaged $428,885,000 (Colorado = $544,521,000, Missouri = -$255,282,000, Nebraska = $358,777,000, and Oklahoma = $1,067,524,000). See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

16 In Q4 2013, Kansas’s trust fund sat at $998,545,000. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp.

17 Growing from $99,480,000 in Q4 2013 to $998,545,000 in Q4 2019. See, e.g., Employment and Training Administration, “Unemployment and Training Administration, “Unemployment insurance data,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSummTable.asp,

18 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “How North Carolina Has Led the Nation With Unemployment Indexing,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/paper/north-carolina-led-the-nation-with-unemployment-indexing/.

19 Jonathan Ingram and Victoria Eardley, “Unemployment insurance reform has strengthened Florida’s economy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/paper/florida-unemployment-insurance-reform/.

20 Hayden Dublois, “How unemployment indexing helped Alabama weather the COVID-19 pandemic,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/paper/unemployment-indexing-helped-alabama/.

21 KS Stat § 44-704 (2021), https://www.ksrevisor.org/statutes/chapters/ch44/044_007_0004.html.

22 N.C.G.S. § 96-14.3 (2013), https://www.ncleg.gov/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/PDF/BySection/Chapter_96/GS_96-14.3.pdf.

23 Fla. Stat. § 443.111 (2022), http://www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&Search_String=&URL=0400-0499/0443/Sections/0443.111.html.

24 Ala. Code 2019 §25-4-74 (2019), http://alisondb.legislature.state.al.us/alison/CodeOfAlabama/1975/25-4-74.htm.