The Biden Administration’s Unlawful Food Stamp Increase Incentivized People to Choose Welfare Over Work

KEY FINDINGS

- The Biden administration unilaterally increased food stamp benefits by adjusting the Thrifty Food Plan.

- This resulted in the largest permanent food stamp increase in program history.

- An estimated 2.4 million Americans have declined employment because of President Biden’s unlawful food stamp expansion.

- If these able-bodied adults joined the workforce, they would fill nearly a quarter of open jobs.

- Congress has three options to reverse course on the Biden administration’s food stamp increase.

The Biden administration unilaterally and unlawfully pushed through the largest permanent food stamp increase in the history of the program by adjusting the Thrifty Food Plan.1 This increase did not happen in a vacuum—it affects the decisions of Americans across the county. People have been disincentivized to work by being paid more to remain on welfare.

In response to the dramatic increase in food stamps, an estimated 2.4 million Americans opted out of joining the workforce.2 All told, these Americans on the sidelines account for a quarter of all job openings across the country.3

Congress should encourage able-bodied adults to work instead of draining resources from the truly needy. Lawmakers can limit the damage caused by the Biden administration by rolling back the Thrifty Food Plan increase, freezing benefits until inflation catches up with the increase, or requiring all future reevaluations to be cost-neutral.

The Biden administration unilaterally and unlawfully increased food stamp benefits by adjusting the Thrifty Food Plan

The Thrifty Food Plan is one of four plans developed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to estimate the average cost of meals.4 Of the four plans, the Thrifty Food Plan is supposed to be the lowest cost.5

The 2018 Farm Bill required USDA to reevaluate the Thrifty Food Plan on a set schedule instead of at USDA’s discretion.6 This reevaluation is meant to update the Thrifty Food Plan based on food prices, food composition data, consumption patterns, and dietary guidance.7-8 Essentially, this process is supposed to update plans based on what is considered a balanced diet and the costs to purchase these foods, not lead to wholesale changes in the Thrifty Food Plan.

This reality is shown by scorings done by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). When Congress was considering the 2018 Farm Bill, the CBO scored the updating of the Thrifty Food Plan to cost nothing.9-12 Just days before the updated Thrifty Food Plan was announced, the CBO estimated only small changes based entirely on inflationary adjustments.13

But instead of minor updates and increases, in 2021 USDA pushed through the largest food stamp expansion in program history, expanding benefits by an average of 27 percent.14 This increase is set to cost up to $250 billion over the next decade, and taxpayers are already feeling the effects.15 Estimates for fiscal year 2022 expected food stamp spending to decline, instead spending spiked by nearly $120 billion.16

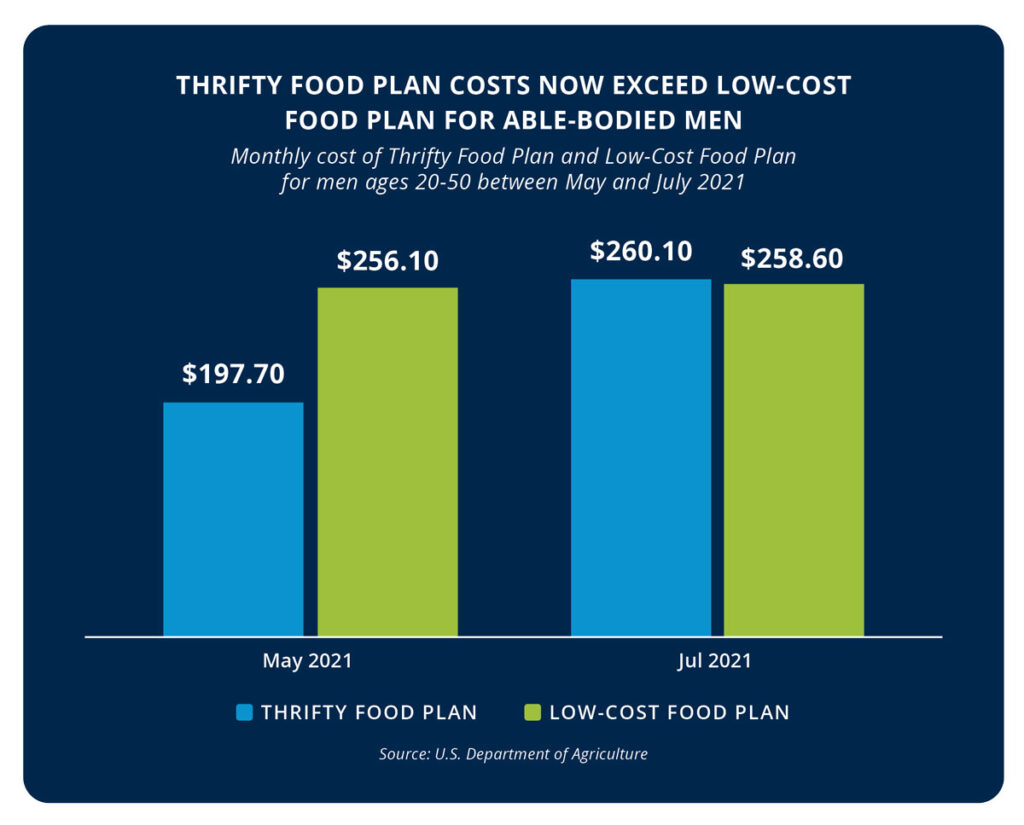

USDA has effectively turned the Thrifty Food Plan into the Low-Cost Food Plan, a step up in USDA’s four food plans. This is a move that Congress had rejected.17 But after the people’s representatives turned it down, unelected bureaucrats unilaterally implemented the proposal.

To make matters worse, USDA cut corners and violated procedures when making their adjustments. Auditors discovered that to increase food stamp benefits, USDA adjusted data inputs, violated multiple guidelines, and shrouded their work in secrecy so that their models could not be replicated.18 These deceptive actions have led to harmful effects, especially in the labor market.

Biden’s food stamp increase is keeping Americans from working

Increases to welfare benefits do not occur in a vacuum—they affect the decisions of millions of recipients. Because of the 27 percent increase in food stamp benefits, an estimated 2.4 million able-bodied Americans chose welfare over work.19 That is 2.4 million Americans who but for the food stamp increase would be gainfully employed right now.

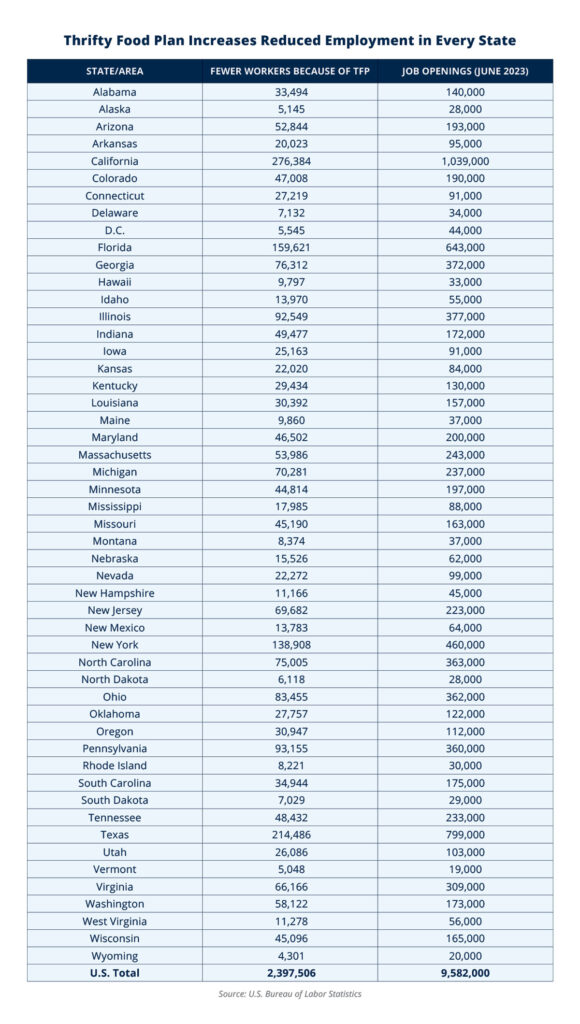

These individuals are not clustered in a couple of states or a single region but are spread throughout all 50 states. Every state has at least 4,000 individuals who chose welfare over work because of the increased food stamp benefits. States like California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas have at least 90,000 fewer workers because of the unlawful food stamp expansion.

All this came at an awful time for employers, especially small businesses. Businesses that survived the pandemic were faced with a labor shortage and an increased cost of labor.20 Job openings rose above 10 million for the first time ever and stayed there for a significant period of time.21-23 The 2.4 million able-bodied individuals that turned to welfare instead of work could have filled nearly a quarter of these openings.

Turning down employment not only hurts employers, but it also harms the individuals staying home collecting food stamps. Able-bodied adults who return to work see their incomes more than double within a year and triple within two years.24-27 Those returning to work also quickly move out of low-wage industries to better-paying jobs.28

Encouraging able-bodied adults on food stamps to seek employment can also give relief to taxpayers and protect the truly needy. Spending on the food stamp program has increased from $17 billion in 2000 to $60 billion in 2019, to a record $119 billion in 2022.29-30 If just a quarter of those sitting on the sidelines found work and increased their incomes to levels where they were ineligible for benefits, it would save taxpayers more than $1.6 billion annually.31 These savings would help ensure that funds remain available for the truly needy without further increasing the program’s bottom line.

Congress has three options to reverse course on Biden’s unlawful food stamp expansion

Congress has three choices to right the Biden administration’s wrong and undo the harm done to employers, taxpayers, and people on food stamps alike.

The first option is to roll back food stamp benefits to their 2020 levels. This would essentially repeal the 27 percent increase that was implemented by the Biden administration by adjusting the Thrifty Food Plan. This would create the best incentive for Americans to get back to work while protecting taxpayer money and funds for the truly needy.

Congress could also freeze food stamp benefits until they match 2020 inflation-adjusted levels. This would avoid the difficulty of reducing benefits but has the drawback of taking years to bring benefits back to their pre-Thrifty Food Plan adjustment levels.

Finally, Congress could require that all future reevaluations of food stamp benefits be cost-neutral. This would ensure that any future increases to benefits only account for inflation and do not entice more Americans to leave the workforce. While this would not remove the increase already put in place, Congress could use this option with one of the other two.

THE BOTTOM LINE: The Biden administration’s unlawful increase in food stamps enticed millions of Americans to choose welfare over work. Congress should pass reforms to instead encourage work over welfare.

The Biden administration implemented the largest permanent increase in the history of food stamps by adjusting the Thrifty Food Plan.32 This giveaway incentivized able-bodied adults to pass on work to take the full benefit amount. Pandemic policies like emergency allotments and pausing work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents further heightened this problem.33-34

The USDA’s 27 percent boost in food stamps convinced an astounding number of Americans to forgo work, and with it, the positive that come from having a job.35-38 An estimated 2.4 million people across the country chose welfare over work. Without this increase, these individuals would have found jobs across industries, filling nearly a quarter of the country’s open jobs.39

It is now up to Congress to flip the switch and push incentives toward work over welfare. Congress should roll back the Thrifty Food Plan increase, freeze benefit amounts until inflation catches up with the increase, or require all future benefit reevaluations to be cost-neutral. Any of these would limit the harm that resulted from the Biden administration’s unlawful Thrifty Food Plan increase.

REFERENCES

1 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “President Biden unilaterally and unlawfully increased food stamp benefits,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/president-biden-increased-food-stamp-benefits/.

2 Authors’ calculations using a macrosimulation model that estimates the total employment effects of a percent change in the effective marginal tax rate based on the change in monthly benefits. The theoretical basis for this model was drawn from The Redistribution Recession: How Labor Market Distributions Contracted the Economy (Mulligan, 2012). The elasticity of labor supply is assumed to be 0.75; see, e.g., Gelber and Mitchell (2011), Nichols and Rothstein (2016), and Corinth et al (2021).

3 There are 9.6 million job openings on the last business day of June according to the Job Openings and Labor Turnover report for August 2023. See, United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Job openings and labor turnover summary,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.nr0.htm.

4 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP and the Thrifty Food Plan,” United States Department of Agriculture (2023), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/thriftyfoodplan.

5 Ibid.

6 Public Law 115-334 (2018), https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ334/PLAW-115publ334.pdf.

7 Ibid.

8 Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, “Thrifty food plan, 2006,” United States Department of Agriculture (2007), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/usda_food_plans_cost_of_food/TFP2006Report.pdf.

9 Congressional Budget Office, “Summary of the estimated effects on direct spending and revenues of H.R. 2, the Agriculture and Nutrition Act of 2018, as introduced on April 12, 2018,” Congressional Budget Office (2018), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr2.pdf.

10 Congressional Budget Office, “Summary of the budgetary effects on direct spending and revenues of H.R. 2, the Agriculture and Nutrition Act of 2018, as ordered reported by the House Committee on Agriculture on April 18, 2018,” Congressional Budget Office (2018), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2018-07/hr2_1.pdf.

11 Congressional Budget Office, “Summary of the budgetary effects of H.R. 2, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, as passed by the House of Representatives on June 21, 2018,” Congressional Budget Office (2018), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2018-07/hr2HouseandSenate.pdf.

12 Keith Hall, “Direct spending and revenue effects of the conference agreement for H.R. 2, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018,” Congressional Budget Office (2018), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2018-12/hr2conf_0.pdf.

13 Congressional Budget Office, “Baseline projections: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” Congressional Budget Office (2021), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2021-07/51312-2021-07-snap.pdf.

14 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “President Biden unilaterally and unlawfully increased food stamp benefits,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/president-biden-increased-food-stamp-benefits/.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Authors’ calculations using a macrosimulation model that estimates the total employment effects of a percent change in the effective marginal tax rate based on the change in monthly benefits. The theoretical basis for this model was drawn from The Redistribution Recession: How Labor Market Distributions Contracted the Economy (Mulligan, 2012). The elasticity of labor supply is assumed to be 0.75; see, e.g., Gelber and Mitchell (2011), Nichols and Rothstein (2016), and Corinth et al (2021).

20 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment cost index—June 2023,” United States Department of Labor (2023), https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/eci.pdf.

21 Jesse Pound, “Job openings surge above 10 million for the first time ever, Labor Department says,” CNBC (2021), https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/09/job-openings-surge-above-10-million-for-first-time-ever-labor-department-says.html.

22 Alicia Wallace, “The number of available US jobs surged in April, complicating the Fed’s strategy,” CNN Business (2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/31/economy/jolts-job-openings-layoffs-april/index.html.

23 Tim Scott, “Job openings decline but still above 10 millions,” U.S. News (2022), https://www.usnews.com/news/economy/articles/2022-11-30/job-openings-decline-but-still-above-10-million.

24 Hayden Dublois, et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements/.

25 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement/.

26 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas/.

27 Josh Archambault, “New report proves Maine’s welfare reforms are working,” Forbes (2016), https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2016/05/19/new-report-proves-maines-welfare-reforms-are-working/?sh=2413b31a3f6a.

28 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has-transformed-floridians-lives/.

29 Food and Nutrition Service, “Supplemental nutrition assistance program participation and costs,” United States Department of Agriculture (2023), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-annualsummary-7.pdf.

30 Jonathan Ingram, “Congress could save taxpayers billions by repealing President Biden’s unlawful food stamp expansion,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/congress-could-save-repealing-bidens-unlawful-food-stamp-expansion/.

31 A quarter of the 2.4 million Americans who would be employed but for the increased Thrifty Food Plan benefits is 600,000 people. This multiplied by the average monthly benefit per person ($230.39) as found at Food and Nutrition Service, “Supplemental nutrition assistance program participation and costs,” United States Department of Agriculture (2023), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-annualsummary-7.pdf equals $138,239,000. This multiplied by 12 to get annual costs equals $1,658,808,000.

32 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “President Biden unilaterally and unlawfully increased food stamp benefits,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/president-biden-increased-food-stamp-benefits/.

33 Hayden Dublois, “Food stamp boosts are bankrupting taxpayers,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/food-stamp-boosts-are-bankrupting-taxpayers/.

34 Alli Fick and Scott Centorino, “The missing tool: How work requirements can reduce dependency and help find absent workers,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/research/one-tool-unleash.economic-recovery-solve-labor-crisis/.

35 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has-transformed-floridians-lives/.

36 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas/.

37 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement/.

38 Hayden Dublois, et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements/.

39 Jonathan Ingram, “House-proposed work requirements would limit dependency, save taxpayer resources, and grow the economy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/house-proposed.work-requirements/.