Five Ways That Congress Can Put a Stop to Food Stamp Fraud

KEY FINDINGS

- Spending on food stamps reached a record-high $119.5 billion in 2022.

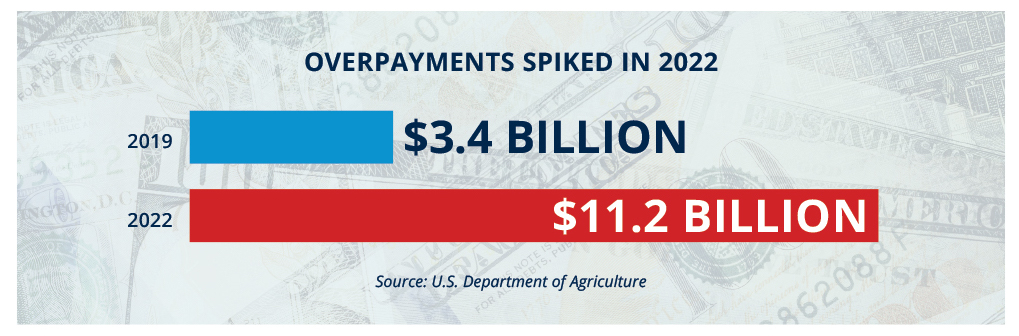

- More than $11 billion was wasted on overpayments in food stamp benefits in 2022.

- Nearly 80 percent of improper payments were the result of errors made by the state agency.

- Countless examples of intentional fraud show that the program is ripe for waste, fraud, and abuse.

Overview

Food stamp spending and enrollment have exploded in the last few years. In 2022, there were more than 41 million Americans on food stamps, compared to approximately 35 million people in 2019.1 In the same four-year period, spending on food stamps grew to a record-high $119.5 billion, up from $60 billion in 2019.2 Food stamp spending nearly doubled, despite only 5.5 million additional enrollees.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is supposed to track states’ payment error rates, which represent both overpayments and underpayments of benefits. In 2022, the payment error rate surged to 11.5 percent compared to just 7.3 percent in 2019.3

However, the true payment error rate is likely much higher. A report from the Government Accountability Office found that nearly 40 percent of cases had a payment error, but most were not included in the payment error rate reported by USDA.4 Only certain instances of payment errors are counted in the reported rate, leaving many other cases unreported.5 Additionally, states have a long history of obfuscating their true error rate by hiding errors and manipulating data to report a lower payment error rate.6 In 2020 and 2021, USDA allowed states to stop conducting the quality control reviews that uncovered improper payments altogether.7

Even among the error rates that are included in reporting, there is wide variation by state, with one state demonstrating a payment error rate of nearly 57 percent.8 Most improper payments are overpayments, meaning that individuals receive more food stamp benefits than they are eligible for.9 Overpayments in food stamps wasted at least $11.2 billion in fiscal year 2022, the highest amount of loss to overpayment in program history.10

Nearly 80 percent of improper payments are due to errors made by the state agency.11 This demonstrates there are gaps in program integrity and a lack of effective controls on benefit distribution that make food stamps ripe for waste, fraud, and abuse. Congress should implement simple program integrity measures to prevent fraud before it happens.

Millions are lost to fraudulent schemes, which can go undetected for years

Fraudsters use several different tactics to defraud the food stamp program. These include trafficking, which occurs when a retailer allows benefits to be exchanged for cash or non-food items. Other fraudulent tactics include individuals claiming benefits for which they are not eligible, card skimming to steal benefits from legitimate enrollees, and claiming benefits in more than one state at a time. Here are some of the worst examples of recent food stamp fraud.

1. 5,000 gallons of mayonnaise and 50 tons of cheese

In 2021, an investigation revealed that two Texas women exchanged cash for food stamps at a store owned by one of the women.12 From 2014 through 2019, the women made 715 fraudulent transactions linked to 83 unique beneficiaries of food stamps.13 Their purchases included nearly 50 tons of American cheese, 22 tons of beans, and more than 5,000 gallons of mayonnaise, which they then sold to a partner in Mexico.14 The fraud cost taxpayers $1.2 million.15

2. Food stamp fraud across four states

A Kansas City, Missouri woman was sentenced to four years in prison for fraudulently applying for food stamps 71 times in four different states.16 In Missouri, she used stolen identity information to file six separate applications for food stamps.17 Her own email and phone number were listed on each application, yet all six were approved.18 She sold the benefit cards for cash each month.19 Additionally, she filed for food stamps in four different states using her own identity and received more than $20,000 worth of benefits in Missouri, Iowa, Indiana, and Illinois.20 She also received more than $45,000 in benefits under stolen identities in these same states.21

3. A millionaire on welfare

In Texas, an investigation revealed that a food stamp recipient failed to disclose his monthly income from a gift-card liquidation business.22 These tax-free earnings averaged to more than $60,000 per month.23 He received food stamps while earning a total of $3 million over the course of four years.24 He also fraudulently claimed Medicaid benefits and failed to disclose income from unemployment benefits.25

4. A $4 million fraud ring

Three people were arrested in Michigan for running a food stamp fraud ring that stole benefits from more than 8,000 people.26 The thieves stole the data from recipients of Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards, primarily from California.27 They then used the data to create new EBT cards and used the food stamp benefits to purchase food at Sam’s Club locations in Detroit.28 Investigators said that there was $4 million in fraudulent purchases made with out-of-state EBT cards.29

Top five reforms to prevent food stamp fraud before it happens

There are commonsense ways to stop fraud in its tracks. Congress should pass the following measures to improve the integrity of the food stamp program and prevent the most common types of fraud before they happen.

1. Prohibit retailers from redeeming their benefits at their own store and disqualify fraudsters from being authorized retailers

A common type of fraud occurs when owners or employees of stores redeem their own benefits for ineligible items or allow others to exchange benefits for cash or purchase ineligible items such as cigarettes, alcohol, or gas.30

In one case of retailer fraud, the owners of a convenience store allowed people to use food stamps to purchase non-food items, including male enhancement pills and gasoline. They also allowed people to exchange benefits directly for cash and charged a 50 percent premium on these illegal transactions.31Approximately $1.27 billion is lost annually to trafficked benefits, an increase from $241 million in 2005.32

USDA estimates that more than 14 percent of retailers engage in trafficking.33 Not all retailers are equally likely to be involved in trafficking—25 percent of small grocery stores are estimated to be involved in trafficking food stamps compared to less than one percent of large grocery stores.34

In 2022, USDA implemented 2,192 administrative sanction actions against retailers who violated program rules, but only permanently disqualified 1,144.35 Retailers who engage in fraud should be permanently disqualified from redeeming food stamps, and the owners of small stores should not be permitted to use their benefits at their own store. Cracking down on retailers involved in fraudulent redemption of benefits would stem the tide of trafficking that costs taxpayers millions each year.

2. Require states to suspend benefits after 60 days of purchases made exclusively out of state

States collect data on where food stamps are used to make purchases and can use data analytics to track when benefits are used exclusively out of state for long periods of time.36 State audits have consistently revealed that out-of-state food stamps activity is a problem. For example, in Pennsylvania, out-of-state activity exceeded $70 million annually.37 An audit in Missouri found that thousands of individuals were using their benefits outside of Missouri for more than three months.38

States should not be on the hook for providing food stamps to non-residents, and reviewing cases in which food stamps are redeemed exclusively out of state can prevent multiple types of fraud. It would prevent people from claiming benefits in two or more states at a time, whether intentionally or accidentally.39 Suspending accounts that make exclusively out-of-state transactions would also prevent people from using stolen identities to claim benefits from a state in which they do not live or stealing EBT card data. It was by flagging excessive out-of-state transactions that investigators were able to uncover the $4 million in fraudulent spending in Detroit.40

3. Clarify and limit authorized users of EBT cards

Food stamps and other government benefits are typically distributed to recipients on an EBT card. Currently, the presumption is that anyone who shows up at a retailer with a card is the legitimate user.41 This presents rampant opportunities for fraud and theft, especially since EBT cards do not have security features to prevent the theft of data.42

The theft of EBT card data is a rapidly growing problem. In 2022, EBT data theft increased by 4,000 percent compared to 2021 in California.43 In Los Angeles County alone, $25 million has been lost to stolen benefits in the first six months of 2023.44

By limiting the authorized users of an EBT card, states can prevent both the sale of food stamps for cash and the theft of food stamps from innocent beneficiaries.

4. Require states to conduct regular, automatic data eligibility cross-checks

A type of fraud occurs when people receive food stamp benefits for which they are not eligible. States already collect and maintain death records, wage records, out-of-state EBT transactions, incarceration records, lottery records, pension data, new hire data, child support enforcement data, and FBI fleeing felon data. All these records can be cross-checked against food stamps recipients so that states can ensure that beneficiaries are truly eligible.45

For example, an audit in Missouri found that more than 2,000 people received food stamps while incarcerated, a violation of program rules.46 Conducting regular eligibility reviews using these data sets would help prevent cases of fraud like failing to report income or continuing to receive benefits while in jail.

5. Require 10-day change reporting for all food stamp enrollees

Another way to prevent people receiving benefits for which they are ineligible is requiring more frequent reporting of changes to beneficiaries’ circumstances. Federal regulations give states two options for reporting changes that impact food stamp eligibility.47 “Simplified reporting” allows households to report only when their income rises above the federal income cap. “Change reporting” requires all changes in income and other eligibility factors to be reported within 10 days.48

Twenty-six states and territories only require food stamp enrollees to report changes if their income rises above the federal eligibility limits, and 25 states have a combination of simplified reporting and change reporting based on the type of household.49 Requiring enrollees to report any change in income or another eligibility factor within 10 days would ensure that people only receive benefits for which they are eligible.

THE BOTTOM LINE: Food stamp fraud costs taxpayers millions and diverts resources from the truly needy. Congress should pass basic program integrity measures to prevent fraud before it happens.

Spending on food stamps has reached record highs, creating more opportunities and incentives for fraud. While the reported rate of improper payments has surged to nearly 12 percent and the amount lost to overpayment surpasses $11 billion annually, the true error rate in food stamps is likely even higher. Current program integrity measures in food stamps are not sufficient to prevent fraud and other errors that waste billions of taxpayer dollars.

Basic measures like eligibility cross-checks and limiting authorized users could prevent the most common types of fraud and theft of benefits. Congress should require more robust program integrity reforms to ensure that criminals cannot take advantage of food stamps, and resources are preserved for the truly needy.