Ineligible Medicaid Enrollees Are Costing Taxpayers Billions

KEY FINDINGS

THE BOTTOM LINE:

POLICYMAKERS SHOULD WORK TO REDUCE IMPROPER PAYMENT RATES AND IMPROVE TRANSPARENCY.

Overview

While initially meant as a program for the truly needy, Medicaid has bloated into a massive welfare program for millions of able-bodied adults dependent upon the government.1Victoria Eardley and Nicholas Horton, “ObamaCare’s not working: How Medicaid expansion is fostering dependency,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/paper/obamacares-not-working-how-medicaid-expansion-is-fostering-dependency–2Nicholas Horton, “Waiting for help: The Medicaid waiting list crisis,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/paper/medicaid-waiting-list Medicaid has rapidly become the largest line item in state budgets, reaching more than $700 billion per year.3Nicholas Horton, “The Medicaid Pac-Man: How Medicaid is consuming state budgets,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/paper/medicaid-pac-man–4Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on quarterly expenditure reporting for the first quarter of fiscal year 2021. See, e.g., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicaid CMS-64 FFCRA increased FMAP expenditure data collected through MBES,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/financial-management/state-budget-expenditure-reporting-for-medicaid-and-chip/expenditure-reports-mbescbes/medicaid-cms-64-ffcra-increased-fmap-expenditure-data-collected-through-mbes/index.html More than 89 million people are now dependent on the program, nearly two and a half times as many as in 2000.5Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and state Medicaid agencies on total Medicaid enrollment between 2000 and 2021.–6Haley Holik and Alli Fick, “Florida’s Entrepreneurship Agenda: A Roadmap to Removing Barriers to Work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/paper/florida-roadmap-to-removing-barriers–7Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2018 actuarial report on the financial outlook for Medicaid,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2018-report.pdf Unfortunately, as Medicaid has grown, so has its mismanagement.

Today, more than one in five dollars spent on Medicaid is improper.8Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “PERM error rate findings and reports,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Medicaid-and-CHIP-Compliance/PERM/PERMErrorRateFindingsandReport Virtually all improper payments are due to eligibility errors, administrative oversights, or outright fraud.9Victoria Eardley and Jonathan Ingram, “How the Trump Administration Can Crack Down on Medicaid Fraud,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/paper/medicaid-fraud-reform-trump-administration And because eligibility errors make up more than 80 percent of improper payments, countless individuals are receiving Medicaid benefits for which they are not eligible.10Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2020 Medicaid & CHIP Supplemental Improper Payment Data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2020-medicaid-chip-supplemental-improper-payment-data.pdf

However, never-before-released data shows the improper payment crisis is even worse in several states. Improper payment rates have reached staggering proportions that threaten the sustainability of the Medicaid program.

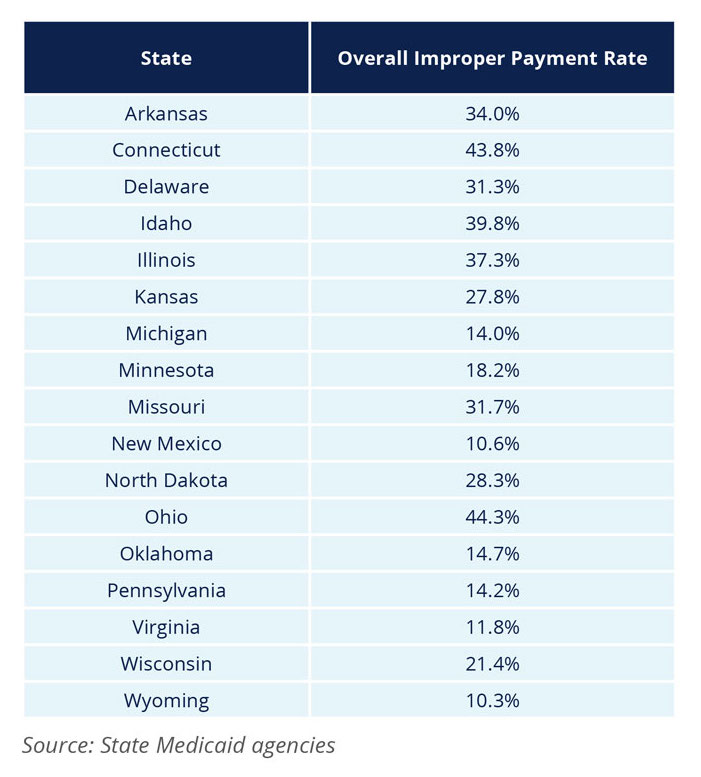

While the national improper payment rate for Medicaid is nearly 22 percent, in some states the situation is far more dire.11Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2020 Medicaid & CHIP Supplemental Improper Payment Data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2020-medicaid-chip-supplemental-improper-payment-data.pdf Never-before-released data from state Medicaid agencies reveals that improper payment rates have reached as high as nearly 50 cents for every Medicaid dollar spent in some states.

Equally concerning is that an overwhelming number of improper payments are due to eligibility errors, signaling that these are not simply administrative blunders—but rather serious situations of countless enrollees receiving resources for which they are not eligible.

Ohio

Ohio’s Medicaid program is nearing insolvency. The program now costs taxpayers nearly $32 billion per year—almost double what it cost a decade ago and more than four times what it cost in 2000.12Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the National Association of State Budget Officers and the Ohio Legislative Service Commission on total Medicaid expenditures between fiscal years 2000 and 2021.–13Nick Samuels et al., “2001 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2002), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/nasbo2001exrep.pdf–14Brian Sigritz et al., “2012 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2013), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/State%20Expenditure%20Report%20(Fiscal%202011-2013%20Data).pdf–15Legislative Budget Office, “Medicaid expenditures: August 2021,” Ohio Legislative Service Commission (2021), https://www.lsc.ohio.gov/documents/budget/documents/infographics/Medicaid%20expenditures%202021%20V2%20NL.pdf These skyrocketing costs have crowded out funds for all other state priorities, as Medicaid now consumes more than half of Ohio’s entire general revenue budget.16Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the Ohio Legislative Service Commission on the proportion of the general revenue budget spent on Medicaid. See, e.g., Legislative Budget Office, “Main operating budget House Bill 110 – as enacted budget in brief,” Ohio Legislative Service Commission (2021), https://www.lsc.ohio.gov/documents/budget/134/mainoperating/EN/budgetinbrief-hb110-en.pdf

The pandemic has only made these problems worse, with enrollment spiking by more than half a million people since February 2020.17Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the Ohio Department of Medicaid on total Medicaid enrollment between February 2020 and November 2021. See, e.g., Ohio Department of Medicaid, “Caseload reports,” Ohio Department of Medicaid (2021), https://medicaid.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/medicaid/stakeholders-and-partners/reports-and-research/caseload-reports/caseload-reports As a result, Ohio’s Medicaid program has been plagued by major budget shortfalls, leading to further cuts.18Catherine Candisky, “Ohio Medicaid caseload soars due to COVID-19, but now program faces budget gap of billions,” Columbus Dispatch (2020), https://www.dispatch.com/story/news/healthcare/2020/11/06/budget-shortfall-may-cause-cuts-ohios-tax-funded-medicaid-program-poor-disabled-because-covid/6165391002–19Matt Wright, “Ohio’s budget crisis: State details cuts to Medicaid,” Fox 8 (2020), https://fox8.com/news/ohios-budget-crisis-state-details-cuts-to-medicaid

Coupled with Ohio’s Medicaid enrollment and spending crisis is an equally pernicious improper payment crisis. Ohio’s Medicaid improper payment rate is an astonishing 44 percent, more than twice the national average.20Data provided by the Ohio Department of Medicaid on Ohio’s most recent results for the payment error rate measurement program. Virtually all of that improper spending—98 percent of it—was caused by eligibility errors.21Data provided by the Ohio Department of Medicaid on Ohio’s most recent results for the payment error rate measurement program. At this pace, Ohio’s Medicaid program is on a clear trajectory towards calamity.

Illinois

Illinois has also struggled with a rapidly growing Medicaid program. The program now costs taxpayers nearly $29 billion per year—more than double what it cost a decade ago and nearly four times what it cost in 2000.22Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the National Association of State Budget Officers and the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services on total Medicaid expenditures between fiscal years 2000 and 2021.–23Nick Samuels et al., “2001 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2002), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/nasbo2001exrep.pdf–24Brian Sigritz et al., “2012 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2013), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/State%20Expenditure%20Report%20(Fiscal%202011-2013%20Data).pdf–25Division of Medical Programs, “Appropriations status report,” Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services (2021), https://www2.illinois.gov/hfs/SiteCollectionDocuments/FY2022AppropriationStatus.pdf; and National Association of State Budget Officers, “2001 State Expenditure Report,” NASBO (2001), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/nasbo2001exrep.pdf Enrollment has swelled to nearly 3.9 million people—growing by more than 750,000 new enrollees in just one year.26Authors’ calculations based on the change in total Medicaid enrollment between fiscal years 2020 and 2021. See, e.g., Division of Medical Programs, “Number of persons enrolled in the entire state,” Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services (2021), https://www2.illinois.gov/hfs/info/factsfigures/Program%20Enrollment/Pages/Statewide.aspx As a result, Illinois’s Medicaid program now consumes nearly one in every three dollars in the state budget.27Brian Sigritz et al., “2021 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2021), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2021_State_Expenditure_Report_S.pdf

But much of this spending is improper. The state’s official improper payment rate sits at more than 37 percent—far above the national average.28Data provided by the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services on Illinois’s most recent results for the payment error rate measurement program. A whopping 95 percent of these improper payments are due to eligibility errors.29Data provided by the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services on Illinois’s most recent results for the payment error rate measurement program.

Missouri

As the Show-Me State gears up to implement ObamaCare’s Medicaid expansion, the state’s Medicaid program is already on fragile footing. Before expansion, Missouri’s Medicaid program cost taxpayers nearly $11 billion—nearly three times what it cost in 2000.30Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the National Association of State Budget Officers on total Medicaid expenditures between fiscal years 2000 and 2021.–31Nick Samuels et al., “2001 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2002), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/nasbo2001exrep.pdf–32Brian Sigritz et al., “2012 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2013), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/State%20Expenditure%20Report%20(Fiscal%202011-2013%20Data).pdf–33Brian Sigritz et al., “2021 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2021), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2021_State_Expenditure_Report_S.pdf The program already consumed nearly 40 percent of total expenditures—the highest level of any non-expansion state in the country.34Brian Sigritz et al., “2021 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2021), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2021_State_Expenditure_Report_S.pdf With Missouri implementing ObamaCare expansion effective October 1, 2021, these budget issues are only going to worsen, as expansion could add nearly 600,000 more enrollees to the program.35Nic Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “How the ObamaCare dependency crisis could get even worse – And how to stop it,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/paper/obamacare-dependency-crisis-get-even-worse-stop

Much of this spending growth has been driven by waste, fraud, and abuse. Nearly one in three dollars Missouri spends on Medicaid is improper, with roughly 70 percent of those improper payments driven by eligibility errors.36Data provided by the Missouri Department of Social Services on Missouri’s most recent results for the payment error rate measurement program. As Missouri implements ObamaCare expansion over the coming months and years, it can only look forward to even greater improper payments in the future.

Kansas

By rejecting ObamaCare’s Medicaid expansion, Kansas has seen lower enrollment and spending growth than many states, helping it better weather the COVID-19 pandemic. But even without expansion, the cost of Kansas’s Medicaid program has more than tripled since 2000, reaching nearly $4.4 billion in 2021.37Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the National Association of State Budget Officers and Kansas Department of Health and Environment on total Medicaid expenditures between fiscal years 2000 and 2021.–38Nick Samuels et al., “2001 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2002), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/nasbo2001exrep.pdf–39Division of Health Care Finance, “Kansas medical assistance report: Fiscal year 2021,” Kansas Department of Health and Environment (2021), https://www.kancare.ks.gov/docs/default-source/policies-and-reports/medical-assistance-report-(mar)/marfy21-apr.pdf?sfvrsn=ca85511b_12 Medicaid now consumes nearly one-fifth of the state’s total expenditures.40Brian Sigritz et al., “2021 state expenditure report,” National Association of State Budget Officers (2021), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/SER%20Archive/2021_State_Expenditure_Report_S.pdf

But nearly 28 percent of Kansas’s Medicaid spending is improper—with an eye-popping 99 percent of these payments attributable to eligibility errors.41Data provided by the Kansas Department of Health and Environment on Kansas’s most recent results for the payment error rate measurement program. Democrat Governor Laura Kelly has repeatedly lobbied to expand Medicaid under ObamaCare, which would add at least 262,000 more able- bodied adults to the program and undoubtedly drive this improper payment rate even higher.42Nic Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “How the ObamaCare dependency crisis could get even worse – And how to stop it,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/paper/obamacare-dependency-crisis-get-even-worse-stop

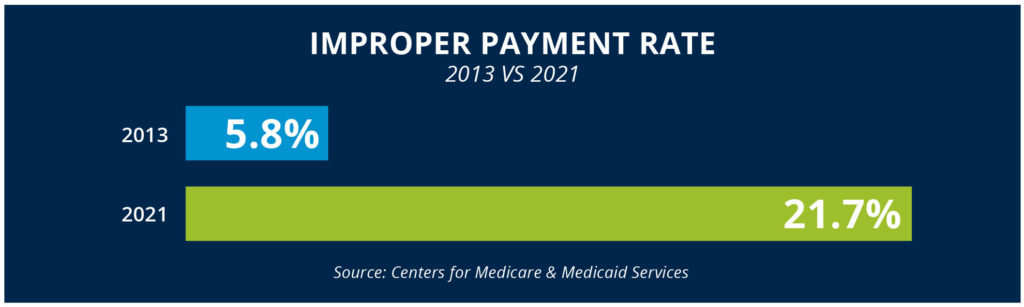

It is no coincidence that the two states with the highest publicly available improper payment rates have expanded Medicaid under ObamaCare. In fact, the national improper payment rate in Medicaid has nearly quadrupled since ObamaCare expansion was first implemented.43Brian Blase and Hayden Dublois, “Improper Medicaid payments have soared since ObamaCare,” National Review (2020), https://www.nationalreview.com/2020/12/improper-medicaid-payments-have-soared-since-obamacare

Federal Medicaid spending has grown by more than $200 billion since 2013—an increase of 80 percent.44Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on federal Medicaid expenditures between fiscal years 2013 and 2021.–45Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Financial management report for fiscal year 2012 through fiscal year 2013,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2014), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/downloads/financial-management-report-fy2012-13.zip–46Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2021 Medicaid and CHIP supplemental improper payment data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2021-medicaid-chip-supplemental-improper-payment-data.pdf Improper payments make up more than 40 percent of that growth.47Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on federal Medicaid expenditures and federal Medicaid improper payments between fiscal years 2013 and 2021.–48Federal Medicaid spending grew by approximately $202 billion between fiscal years 2013 and 2021, while federal Medicaid improper payments grew by approximately $84 billion.–49Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Financial management report for fiscal year 2012 through fiscal year 2013,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2014), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/downloads/financial-management-report-fy2012-13.zip–50Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2021 Medicaid and CHIP supplemental improper payment data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2021-medicaid-chip-supplemental-improper-payment-data.pdf–51Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “PERM error rate findings and reports,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Medicaid-and-CHIP-Compliance/PERM/PERMErrorRateFindingsandReport Medicaid expansion not only coincided with the spike in improper payments, but were a key cause of it. The Obama administration paused annual reports auditing Medicaid spending during the rollout years of Medicaid expansion, both delaying and concealing critical information regarding improper payment rates.52Brian Blase and Aaron Yelowitz, “Why Obama stopped auditing Medicaid,” Wall Street Journal (2019), https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-obama-stopped-auditing-medicaid-11574121931

In California, auditors found nearly 450,000 Medicaid expansion enrollees who were ineligible or potentially ineligible.53Office of the Inspector General, “California made Medicaid payments on behalf of newly eligible beneficiaries who did not meet federal and state requirements,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region9/91602023.pdf In Ohio, federal auditors found that nearly 300,000 of the state’s then-481,000 expansion enrollees were potentially ineligible, undoubtedly explaining why Ohio has one of the highest improper payment rates in the nation.54Office of Inspector General, “Ohio did not correctly determine Medicaid eligibility for some newly enrolled beneficiaries,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020), https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/51800027.pdf Similar audits and reports in other expansion states—such as Colorado, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, New Jersey, and New York—have reached equally alarming conclusions.55Office of Inspector General, “California made Medicaid payments on behalf of non-newly eligible beneficiaries who did not meet federal and state requirements,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region9/91702002.pdf–56Medicaid Audit Unit, “Medicaid eligibility: Modified adjusted gross income determination process,” Louisiana Legislative Auditor (2018), https://www.lla.la.gov/PublicReports.nsf/0C8153D09184378186258361005A0F27/$FILE/summary0001B0AB.pdf–57Financial Audit Division, “Medical assistance eligibility: Adults without children,” Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor (2018), https://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/fad/pdf/fad1818.pdf–58Office of the State Auditor, “NJ FamilyCare eligibility determinations,” New Jersey Office of Legislative Services (2018), https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/legislativepub/auditor/544016.pdf–59Office of Inspector General, “New York did not correctly determine Medicaid eligibility for some newly enrolled beneficiaries,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region2/21501015.pdf–60Office of the Inspector General, “Colorado did not correctly determine Medicaid eligibility for some newly enrolled beneficiaries,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2019), https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region7/71604228.asp–61Office of the Inspector General, “Kentucky did not correctly determine Medicaid eligibility for some newly enrolled beneficiaries,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2017), https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region4/41508044

But as bad as Medicaid expansion’s effect on improper payment rates is, we still do not know the full scope of this out-of-control crisis.

The True Extent of Improper Payments is Still Hidden.

In 2021, improper Medicaid spending hit a record high.62Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “PERM error rate findings and reports,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Medicaid-and-CHIP-Compliance/PERM/PERMErrorRateFindingsandReport But official reports may only scratch at the surface of waste, fraud, and abuse in the Medicaid program, as the true extent of improper payments remains hidden.

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services suspended the annual reports auditing Medicaid spending for 17 states, including large expansion states like California, Massachusetts, and New Jersey.63Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2021 Medicaid and CHIP supplemental improper payment data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2021-medicaid-chip-supplemental-improper-payment-data.pdf

Worse yet, Congress imposed federal Medicaid handcuffs on states in 2020 that provided a temporary boost in federal Medicaid funding in exchange for states agreeing not to remove ineligible enrollees from their Medicaid programs.64Jonathan Ingram et al., “Extra COVID-19 Medicaid funds come at a high cost to states,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/paper/covid-19-medicaid-funds–65Scott Centorino and Chase Martin, “Congress’s Medicaid funding increase creates massive legal uncertainty for states during the COVID-19 crisis,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/paper/covid-19-medicaid-funding–66Hayden Dublois, “Locked-in: How Congress’s Medicaid handcuffs have caused Medicaid to spiral out of control,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/congress-medicaid-handcuffs As a result, millions of individuals are now locked into coverage for which they are no longer eligible.67Hayden Dublois, “Locked-in: How Congress’s Medicaid handcuffs have caused Medicaid to spiral out of control,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/congress-medicaid-handcuffs–68Haley Holik and Alli Fick, “Florida’s Entrepreneurship Agenda: A Roadmap to Removing Barriers to Work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/paper/florida-roadmap-to-removing-barriers

Medicaid enrollment has grown by an estimated 18 million people since February 2020.69Haley Holik and Alli Fick, “Florida’s Entrepreneurship Agenda: A Roadmap to Removing Barriers to Work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/paper/florida-roadmap-to-removing-barriers State data reveals that more than 90 percent of that growth has been caused by states’ inability to remove ineligible enrollees. This disastrous arrangement has further muddied the waters of determining accurate improper payment estimates.

BOTTOM LINE: Policymakers should work to reduce improper payment rates and improve transparency.

States do not need to wait for the Biden administration to act in order to get improper Medicaid spending under control. State policymakers have a wide variety of tools at their disposal to reduce improper payments and improve transparency.

FIRST, states should remove the Medicaid handcuffs imposed by Congress. By rejecting the temporary extra funding, states can regain control over their Medicaid programs, conduct redeterminations and renewals, and remove ineligible individuals from their programs.

SECOND, states can implement Medicaid program integrity measures, such as cross-checking Medicaid enrollees against death, employment, wage, and residency records. States can also verify Medicaid applications received through the ObamaCare exchange and prohibit individuals from self-attesting to eligibility without verification. In 2021, Arkansas and Texas enacted several of these commonsense program integrity reforms to reduce Medicaid improper payments and preserve Medicaid resources for the most vulnerable.70Arkansas General Assembly, “Act 780 of 2021,” State of Arkansas (2021), https://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/Acts/FTPDocument?path=%2FACTS%2F2021R%2FPublic%2F&file=780.pdf&ddBienniumSession=2021%2F2021R–71Texas General Assembly, “SB. 1341 of 2021,” State of Texas (2021), https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/87R/billtext/pdf/SB01341F.pdf

FINALLY, states can require their Medicaid agencies to submit annual reports on improper payment amounts and causes in order to better monitor and address the issue.

It is long past time for policymakers to ensure that Medicaid is preserved for truly needy Americans—not for waste, fraud, and abuse.

APPENDIX: STATES’ MOST RECENT IMPROPER PAYMENT RATES (2019)