Work Requirements Work: How Expanding Food Stamp Work Requirements Can Continue to Break the Cycle of Dependency

KEY FINDINGS

- There are roughly 42 million food stamp enrollees nationwide, but most able-bodied adults on food stamps do not work at all.

- Millions of able-bodied adults on food stamps are not subject to any real work requirement, including able-bodied parents.

- Work requirements have a proven track record of moving able-bodied adults from welfare to work and breaking the cycle of dependency.

- Expanding the age limit for the ABAWD work requirement and implementing commonsense work requirements for able-bodied parents would help lift millions of able-bodied adults out of dependency and into self-sufficiency.

- Moving more able-bodied adults from welfare to work would save taxpayers billions.

Background

Today, there are roughly 42 million food stamp enrollees nationwide.1 Despite there being nearly 10 million open jobs throughout the country, the number of able-bodied, childless adults on food stamps remains near record-high levels.2-4 Even worse, the vast majority of these able-bodied, childless adults are not working at all—trapping them in a cycle of dependency.5

Federal law provides that able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) must work, train, or volunteer at least part time to remain eligible for food stamps.6 But many states waive work requirements for as many able-bodied adults as possible and, during the pandemic, these work requirements were suspended altogether.7-8 However, prior to the pandemic, some states had reinstated work requirements, and these states saw great success in moving able-bodied adults from welfare to work.9-12

Unfortunately, some able-bodied adults have been left behind. The ABAWD work requirement currently caps the age limit for able-bodied adults at 49—though this will gradually increase to 50 later this year and then to 55 over time.13-14 Worse yet, able-bodied parents on food stamps have no real work requirement.15 Some able-bodied parents may theoretically be subject to work training programs administered by states, but very few states require participation.16

To broaden the power of work requirements and help a larger number of able-bodied adults break free from the chains of dependency, an imminent change is needed.

Most able-bodied adults on food stamps do not work at all

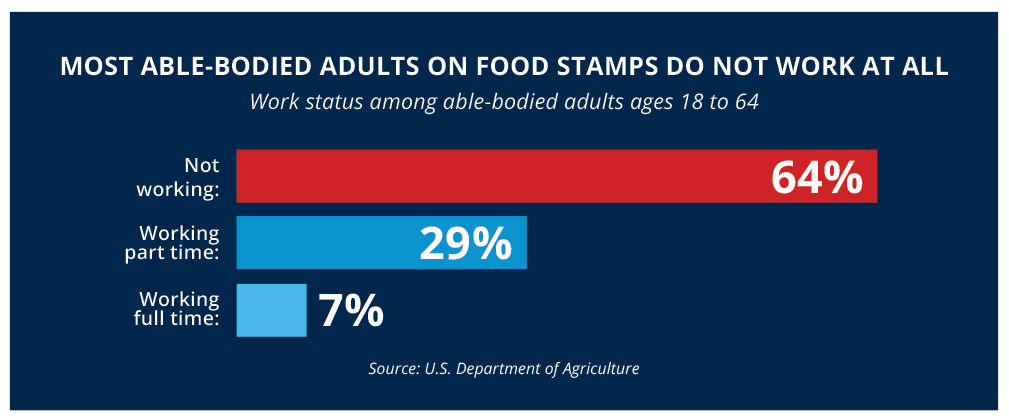

Many food stamp enrollees are trapped in a vicious dependency cycle, without an incentive to break free. Data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows that among non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 to 64 enrolled in the food stamp program, 64 percent are not working at all—more than six in 10 enrollees nationwide.17 Even more shocking, only seven percent are working full time.18

Nationwide, there are nearly 10 million open jobs that employers are desperate to fill—with nearly two open jobs for every unemployed person seeking work.19 Even better, most jobs being created do not require a college degree, advanced training, or prior experience.20 Despite open jobs being plentiful—a near-record high—millions of able-bodied adults are sitting on the sidelines rather than entering the workforce.21 With recent data suggesting that nearly two million workers are missing from the labor force as compared to before the pandemic, the country is facing one of the worst worker shortages in modern history.22

Able-bodied parents on food stamps have no real work requirement

In the food stamp program, able-bodied adults are typically subject to one of two work requirements.23 The current ABAWD work requirement requires able-bodied, childless adults between the ages of 18 to 49 to work, train, or volunteer part time to remain eligible for food stamps—but this is set to increase over time.24 The general work requirement applies to all work registrants (able-bodied adults under 60 without young children) and requires work registration, taking a suitable job if offered, and participating in state-administered workforce programs if assigned.25

While most able-bodied parents fall in the work registrant category, states rarely assign work registrants to Employment and Training programs—participation is completely voluntary in most states.26 Able-bodied parents that are explicitly exempt from the general work requirement are those with children under the age of six.27 But in practice, able-bodied parents have no real work requirement—unless a state can prove that a suitable job offer was refused.

More than 10 million parents receive food stamps, near a record high.28-30 But most of these parents do not work at all.31

This represents a real problem within the food stamp program. Despite federal law providing that most enrollees are subject to some sort of work requirement, most states have chosen to either waive those work requirements or devise ways to avoid enforcing them.32-34 Making matters worse, able-bodied parents on the program have no explicit work requirement.

Some families are trapped in the cycle of dependency for generations, with self-sufficiency seemingly unattainable. To help break this cycle, able-bodied parents should be subject to work requirements.

Work requirements should be expanded to include more able-bodied adults

Currently, able-bodied, childless adults between the ages of 18 to 49 are subject to the ABAWD work requirement.35 But in 2023, Congress passed legislation to phase in older able-bodied adults over time.36 By 2025, ABAWDs under 55 will have to work, train, or volunteer at least part time to continue receiving benefits.37 This work requirement only applies to a fraction of able-bodied adults on food stamps, and while this is a good first step, there is more work to be done.

Despite the age limits of the food stamp work requirement, Americans are working well beyond the age of 54, as the average retirement age in 2016 was 64—and individuals must be 65 to qualify for Medicare and 67 to qualify for full Social Security benefits.38-40 Not only are Americans over the age of 54 still working and earning higher salaries than younger Americans, but the ABAWD work requirement only captures a fraction of the workforce.41

Congress should extend the work requirement to able-bodied adults without dependents up to the age of 65. In doing so, millions of additional food stamp enrollees nationwide can experience the power of work.

Work requirements work

Work requirements have a long history of being a highly effective tool for helping food stamp enrollees move from dependency to work. States that have implemented these commonsense requirements have experienced outstanding results.

ARKANSAS

- Within two years of implementing work requirements, able-bodied, childless adult enrollment dropped by 70 percent.42

- Within two years of leaving welfare, Arkansans saw their incomes triple.43

- Taxpayers saved $28 million annually.44

FLORIDA

- Two years after implementing work requirements, the number of able-bodied adults without dependents on food stamps dropped by 94 percent.45

- Floridians went back to work in more than 1,100 unique industries.46

MISSISSIPPI

- Less than three years after implementing welfare reform, enrollment among able-bodied, childless adults fell by 72 percent.47

- Mississippians found jobs in more than 700 unique industries.48

- Incomes more than doubled within two years of moving from welfare to work.49

- Taxpayers saved $93 million annually.50

MISSOURI

- Less than a year after implementation, the number of able-bodied adults without dependents on food stamps dropped by 85 percent.51

- Within three months, these able-bodied adults saw their incomes rise by 70 percent, and eventually doubling—more than offsetting any loss of benefits.52

Moving more able-bodied adults from welfare to work would save taxpayers billions

Congress should look to these states as an example and reform the food stamp program nationwide. By expanding work requirements to more able-bodied adults, taxpayers could save up to $64 billion over the next decade alone.53-64 If Congress paired this reform with a plan to end states’ waiver abuses, those savings would leap to nearly $242 billion.65-66

THE BOTTOM LINE: It is time for Congress to bring common sense back to the food stamp program.

While federal law provides that there are work requirements for able-bodied adults on food stamps, far too often these work requirements are limited in nature or are waived by states altogether. Even worse, states with work requirements on the books make participation voluntary, leaving many able-bodied adults behind.

Work requirements have a proven track record of moving food stamp enrollees from welfare to work, leading to higher incomes, and less dependency. It is time for Congress to bring common sense back to the food stamp program by expanding the age limit of the ABAWD work requirement and mandating work requirements for able-bodied parents on the program. Doing so will break the cycle of dependency and help move more able-bodied adults to self-sufficiency.

REFERENCES

1 Food and Nutrition Service, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Number of persons participating,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-persons-7.pdf.

2 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Job openings and labor turnover – June 2023,” U.S. Department of Labor (2023), https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.nr0.htm.

3 Jonathan Bain and Jonathan Ingram, “Waivers gone wild: Congress must crack down on food stamp loopholes,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/waivers-gone-wild-food-stamp-loopholes.

4 Author’s calculations based on the estimated number of able-bodied adults without dependents in the food stamp program compared to total program enrollment.

5 Jonathan Bain and Jonathan Ingram, “Waivers gone wild: Congress must crack down on food stamp loopholes,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/waivers-gone-wild-food-stamp-loopholes.

6 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP work requirements,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/work-requirements.

7 Jonathan Bain and Jonathan Ingram, “Waivers gone wild: Congress must crack down on food stamp loopholes,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/waivers-gone-wild-food-stamp-loopholes.

8 Ibid.

9 Jonathan Ingram and Nic Horton, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement.

10 Hayden Dublois et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements.

11 Jonathan Ingram and Nic Horton, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has-transformed-floridians-lives.

12 Jonathan Ingram and Nic Horton, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas.

13 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP – Noticing able-bodied adults without dependents before reinstating the time limit,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/noticing-abawds-before-reinstating-time-limits.

14 FGA, “FGA applauds Speaker McCarthy and House Republicans for bold debt ceiling negotiations,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/press/fga-applauds-speaker-mccarthy-and-house-republicans-for-bold-debt-ceiling-negotiations.

15 Jonathan Ingram et al., “The case for expanding food stamp work requirements to parents,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/case-expanding-food-stamp-work-requirements-parents.

16 Ibid.

17 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the work status of non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 64 receiving food stamps between October 2019 and February 2020. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Fiscal year 2020 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program quality control database,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://snapqcdata.net/sites/default/files/2022.12/qcfy2020_st.zip.

18 Ibid.

19 Jonathan Ingram, “House-proposed work requirements would limit dependency, save taxpayer resources, and grow the economy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/house-proposed-work-requirements.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP work requirements,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/work-requirements.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Alli Fick and Scott Centorino, “The missing tool: How work requirements can reduce dependency and help find absent workers,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/research/one-tool-unleash-economic-recovery-solve-labor-crisis.

27 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP work requirements,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/work-requirements.

28 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the number of non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 64 receiving food stamps between June 2020 and September 2020 with children in the household. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Fiscal year 2020 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program quality control database,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://snapqcdata.net/sites/default/files/2022.12/qcfy2020_st.zip.

29 Five states provided the U.S. Department of Agriculture with no data for the months of June 2020 through September 2020. For these states, the national average increase in enrollment among non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 49 with children in the household from the period between October 2019 and February 2020 to the period between June 2020 and September 2020 was applied to those five state states’ average enrollment among non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 49 with children in the household during the period between October 2019 and February 2020.

30 The U.S. Department of Agriculture uses quality control data to produce demographic characteristics reports for food stamp enrollees. Fiscal year 2020 data is the most recent available for this purpose. However, overall enrollment has changed little since this data was produced. Between June 2020 and September 2020, overall food stamp enrollment averaged nearly 42.8 million. In April 2023, the most recent month that data is available, overall food stamp enrollment remained elevated at 41.9 million. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP monthly state participation and benefit summary,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource-files/SNAPZip69throughCurrent-4.zip.

31 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the work status of non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 64 receiving food stamps between October 2019 and February 2020 with children in the household. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Fiscal year 2020 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program quality control database,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://snapqcdata.net/sites/default/files/2022.12/qcfy2020_st.zip.

32 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP work requirements,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/work-requirements.

33 Jonathan Bain and Jonathan Ingram, “Waivers gone wild: Congress must crack down on food stamp loopholes,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/waivers-gone-wild-food-stamp-loopholes.

34 Alli Fick and Scott Centorino, “The missing tool: How work requirements can reduce dependency and help find absent workers,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/research/one-tool-unleash-economic-recovery-solve-labor-crisis.

35 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP work requirements,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/work-requirements.

36 FGA, “FGA applauds Speaker McCarthy and House Republicans for bold debt ceiling negotiations,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/press/fga-applauds-speaker-mccarthy-and-house-republicans-for-bold-debt-ceiling-negotiations.

37 Jonathan Ingram, “House-proposed work requirements would limit dependency, save taxpayer resources, and grow the economy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/house-proposed-work-requirements.

38 Center for Retirement Research, “Average retirement age for men and women, 1962-2016,” Boston College (2018), http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Avg_ret_age_men.pdf.

39 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, “Who’s eligible for Medicare?,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2022), https://www.hhs.gov/answers/medicare-and-medicaid/who-is-eligible-for-medicare/index.html#:~:text=Generally%2C%20Medicare%20is%20for%20people,Part%20A%20(Hospital%20Insurance).

40 Social Security Administration, “Starting your retirement benefits early,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2023), https://www.ssa.gov/benefits/retirement/planner/agereduction.html.

41 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by age and sex,” U.S. Department of Labor (2023), https://www.bls.gov/charts/usual-weekly-earnings/usual-weekly-earnings-current-quarter-by-age.htm.

42 Jonathan Ingram and Nic Horton, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Jonathan Ingram and Nic Horton, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has-transformed-floridians-lives.

46 Ibid.

47 Jonathan Ingram and Nic Horton, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Hayden Dublois et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements.

52 Ibid.

53 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by a proprietary microsimulation model estimating the enrollment and expenditure effects of extending work requirements to non-disabled adults, disaggregated by age and household composition.

54 The proprietary microsimulation model incorporates data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the number of non-disabled adults receiving food stamps between June 2020 and September 2020, average per-person benefits for such adults, the maximum allotments for such adults’ households, and changes in the maximum allotment between fiscal year 2020 and fiscal year 2023, disaggregated by state, and data provided by the Congressional Budget Office on projected future changes to the Thrifty Food Plan and average enrollment over the next decade.

55 The proprietary microsimulation model projected each state’s enrollment decline as the share of non-disabled adults in each disaggregated eligibility category not working at all between October 2019 and February 2020. This projected decline is consistent with actual experiences in states that have implemented work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents.

56 When Kansas implemented work requirements in 2014, the number of able-bodied adults on the program dropped by 75 percent. See, e.g., Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “The power of work: How Kansas’ welfare reform is lifting Americans out of poverty,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2016), https://thefga.org/research/report-the-power-of-work-how-kansas-welfare-reform-is-lifting-americans-out-of-poverty.

57 When Maine implemented work requirements in 2015, the number of able-bodied adults on the program dropped by 91 percent. See, e.g., Jonathan Ingram and Josh Archambault, “New report proves Maine’s welfare reforms are working,” Forbes (2016), https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2016/05/19/new-report-proves-maines.welfare-reforms-are-working.

58 When Arkansas implemented work requirements in 2016, the number of able-bodied adults on the program dropped by 70 percent. See, e.g., Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas.

59 When Florida implemented work requirements in 2016, the number of able-bodied adults on the program dropped by 94 percent. See, e.g., Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has-transformed-floridians-lives.

60 When Mississippi implemented work requirements in 2016, the number of able-bodied adults on the program dropped by 72 percent. See, e.g., Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food.stamps-work-requirement.

61 When Missouri implemented work requirements in 2016, the number of able-bodied adults on the program dropped by 85 percent. See, e.g., Jonathan Bain et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work.requirements.

62 The maximum food stamp allotment increased by roughly 45 percent between fiscal year 2020 and fiscal year 2023. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Cost of living adjustment (COLA) information,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/allotment/COLA.

63 The Congressional Budget Office projects that the Thrifty Food Plan, on which maximum food stamp allotments are based, will increase by 8.7 percent between 2023 and 2024 and increase by roughly 19.6 percent between 2024 and 2033. See, e.g., Congressional Budget Office, “February 2023 baseline projections: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” Congressional Budget Office (2023), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2023-02/51312.2023-02-snap.pdf.

64 The Congressional Budget Office projects that average food stamp enrollment will increase by 0.2 percent between 2023 and 2024 and decrease by roughly 16.9 percent between 2024 and 2033. See, e.g., Congressional Budget Office, “February 2023 baseline projections: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” Congressional Budget Office (2023), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2023-02/51312-2023-02-snap.pdf.

65 Author’s calculations based upon data provided by a proprietary microsimulation model estimating the enrollment and expenditure effects of extending work requirements to non-disabled adults, disaggregated by age and household composition, and eliminating geographic waivers from those work requirements.

66 States report that approximately two-thirds of able-bodied adults without dependents who would be subject to existing work requirements live in areas operating under waivers. See, e.g., Jonathan Ingram, “House-proposed work requirements would limit dependency, save taxpayer resources, and grow the economy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/house-proposed-work-requirements.