Americans Deserve New Health Options—And Policymakers Can Deliver

Key Findings

- An ICHRA-anchored pool with a new federal reinsurance program would empower consumers.

- Splitting the risk pools would offer 25 percent lower premiums.

- A family of four could save more than $6,200 per year.

- This health care transformation can be maximized with other reforms.

Overview

Affordability of health care remains a top concern for the countless Americans struggling to keep

up with the cost of health insurance.1 Nearly 30 million people are without health insurance entirely, and roughly two-thirds of the uninsured cite insurance costs as the reason for going without insurance.2-3 For those enrolled in the individual marketplace, affordability can be an almost insurmountable challenge.4

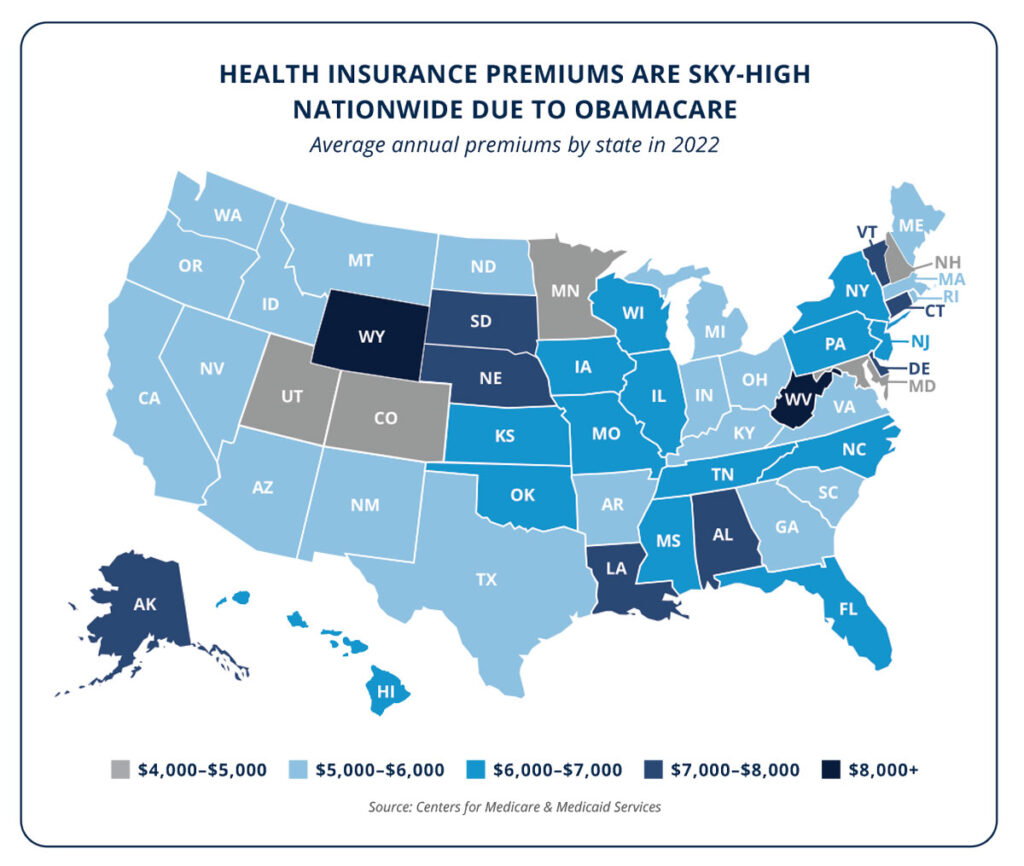

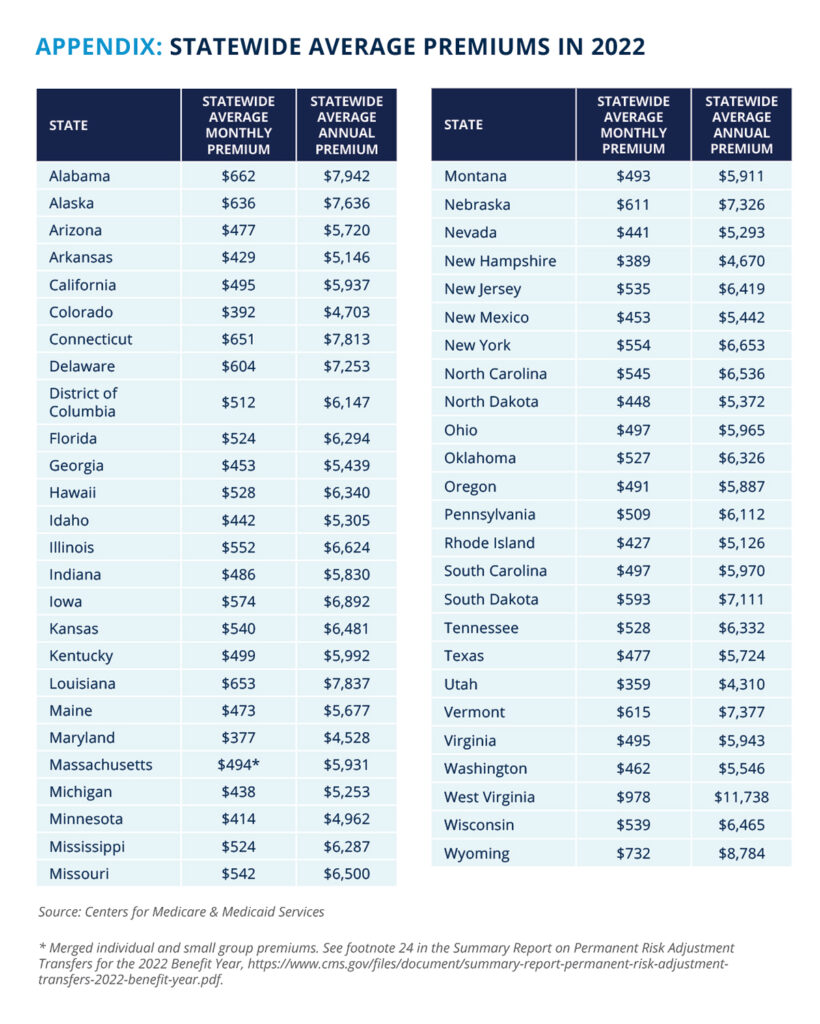

One of the main reasons health care continues to be unaffordable is rising insurance premiums. Since ObamaCare was implemented, premiums on the individual market have more than doubled.5-6

In 2022, the average premium was more than $6,000 per person, with an out-of-pocket maximum of as much as $9,100.7-8 Americans enrolled in this coverage will spend more on health insurance than on gas or groceries in a given year.9-10 In some states, premiums are even higher—the statewide average premium in West Virginia is nearly $12,000 per year before paying any required out-of-pocket costs for care.11

Individual market premiums are through the roof due to the fundamental features of ObamaCare. Several onerous restrictions, such as community rating, benefit mandates, and guaranteed issue requirements, lead to higher costs. Furthermore, low-risk, and therefore lower-cost, enrollees are lumped in the same risk pool as high-risk, higher-cost exchange enrollees—making premiums all the more expensive for lower-risk consumers who are unlikely to receive ObamaCare subsidies.

These challenges place even greater pressure on taxpayers to subsidize insurance, punish job creators with limited options, and promote government dependency through taxpayer-subsidized coverage. In short, the status quo is unworkable. Fortunately, innovative solutions are available and the costly, burdensome, and flawed structure of ObamaCare is not the only way forward.

New Health Options Market: An ICHRA-anchored pool with a new federal reinsurance program would empower consumers

Federal lawmakers can build on existing policies to advance meaningful reform that drives down premiums. Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangements (ICHRAs) allow employers to give tax-privileged funds directly to employees to buy their own coverage.12 Rather than directly managing employee health plans, ICHRAs give employers an alternative funding mechanism to provide employees with a cash benefit with the same pre-tax preference afforded to traditional employer-sponsored insurance. In turn, employees use ICHRAs to purchase a plan on the individual market. ICHRAs give employees more control over their health insurance benefits and introduce more consumer power into the market.13

The 2020 Economic Report of the President anticipated that younger and healthier workers would be drawn to “the typical individual market coverage of relatively higher deductibles and more limited provider networks due to their lower premiums.”14 But this can only work if premiums are affordable in the individual market. The upward pressure on premiums from the existing, single risk pool structure—where ICHRA users are combined with higher-risk, more expensive exchange enrollees—drives up premiums across the board and makes using ICHRAs to purchase plans in the individual market less attractive.

Because of the differences in risk levels across different enrollees, ICHRAs would be better leveraged if enrollees were not lumped into the same risk pool as exchange enrollees. For example, the average risk score for individual market exchange enrollees is 25 percent higher than those in the small group market—which is where ICHRA beneficiaries would be migrating from.15 Simply put, forcing both exchange and non-exchange enrollees into a single pool drives up costs for enrollees dealing directly with insurers, even if they are using tax-favored ICHRAs. This presents the opportunity for an innovative solution: Create a separate and parallel risk pool designed to serve employees using ICHRAs and individuals who want to buy plans directly from insurers. This would open up a parallel, market-driven risk pool with lower premiums. A new “opt-in” pool would enable individuals to migrate to a more affordable plan. Importantly, this new pool would not result in changes to existing benefit mandates, guaranteed issue, or variation in premiums based on health or gender. It would also not force any exchange enrollee in the current risk pool to migrate to the new pool. They can keep their free or highly subsidized plans.

How would the new risk pool be different? Primarily, it would not share one of the mandates that drive up costs in the current risk pool and instead allow premiums based on age to vary with a five-to-one ratio as opposed to the current three-to-one ratio. This would maximize savings for younger Americans with ICHRAs and encourage them to purchase insurance.

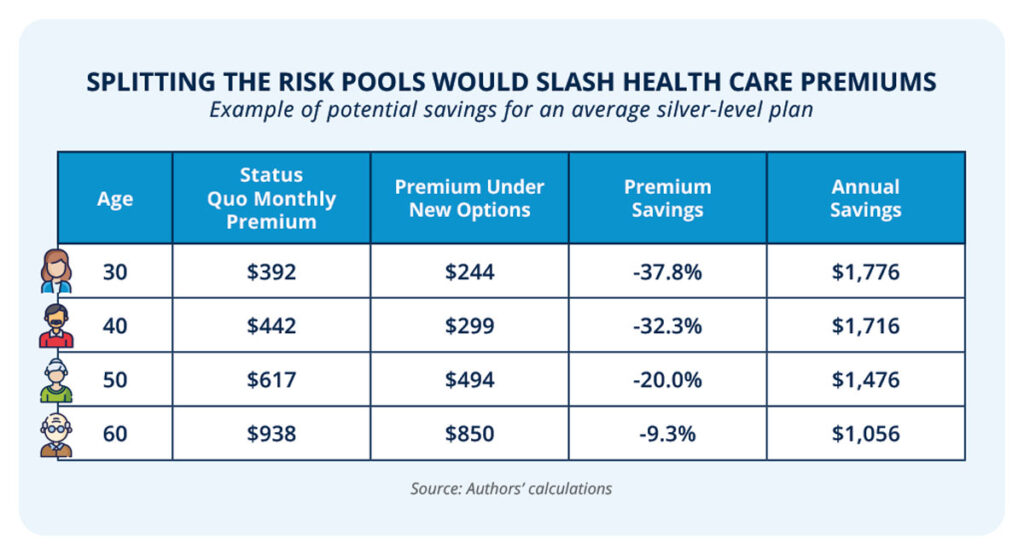

Splitting the risk pools would offer 25 percent lower premiums

ObamaCare forces all enrollees into a single risk pool, penalizing lower-risk individuals. Actuarial analyses of splitting the risk pools coupled with a reinsurance program reveal substantial premium savings. Under a separate risk pool financed by employer and employee ICHRA contributions, combined with a low-cost federal reinsurance program, would allow for substantial savings when an individual purchases directly from an insurer instead of the ObamaCare exchange. Premiums in this new risk pool would be an average of 25 percent lower than premiums on the exchange today.16-18 For certain age groups, the premium savings would be even greater.

The savings to families would be tremendous. Under this proposal, a family of four could see savings of more than $6,200 per year—a 36 percent reduction in premiums.19

Premiums for a parallel risk pool could be further reduced through a reinsurance program

Reinsurance programs help limit risk by spreading the costs across participating insurers.20 A reinsurance program would use federal funding to subsidize high-cost claims at a set level to further reduce costs overall. Low- and no-subsidy enrollees paying high premiums in the current, single risk pool ObamaCare exchanges would be able to access lower premium plans, further driving down premiums in the parallel risk pool overall. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services spent approximately $7.8 billion to cover roughly 55 percent of the cost of medical claims between $45,000 and $250,000 through a temporary reinsurance program for the individual market.21-22 This amounts to a monthly cost averaging nearly $50 per enrollee and reduced premiums between six and 11 percent.23-24 That reinsurance program for the current risk pool subsequently expired. This new reinsurance program would operate at the same $50 per member, per month level, with a $6 billion annual cap, and would similarly expire once the market stabilizes after a few years.

In summary, codifying existing ICHRA rules, allowing funding of new plans with ICHRAs, creating an exception to ObamaCare’s single risk pool requirement and eliminating the three-to-one limit for the new, parallel risk pool, and constructing a reinsurance program would transform the health insurance landscape. Implementing this proposal would place downward pressure on premiums for millions of Americans, providing much-needed relief for consumers suffering from the high costs brought on by ObamaCare.

This health care transformation can be maximized with other reforms

A new risk pool structure and reinsurance program would put downward pressure on premiums and bring much-needed relief for consumers. But coupling these changes with additional reforms would maximize the impact. These policies include promoting high-value care by creating flexibility for out-of-network care, disclosing lower cash prices, and codifying commonsense regulatory changes.

Flexibility for out-of-network care

A major consequence of ObamaCare is the narrowing of provider networks.25 Narrow networks can often leave patients without a reasonable in-network provider, meaning they are forced to go outside their plan’s network to find the care they need. Under current law, out-of-pocket expenses do not count towards in-network deductibles, even if the provider is more affordable. This makes the cost of care even more burdensome for the patient and limits cost savings for the entire insurer network. Patients deserve access to the care they need, regardless of network, especially when out-of-network providers offer low-cost services.

Providing patients with the flexibility to seek out-of-network care by allowing lower cost out-of-network providers to count toward in-network deductibles—something already allowed in Georgia—would not only alleviate the financial burden on patients who have nowhere else to turn, but would also lead to a more competitive system with an incentive to shop based on price.26

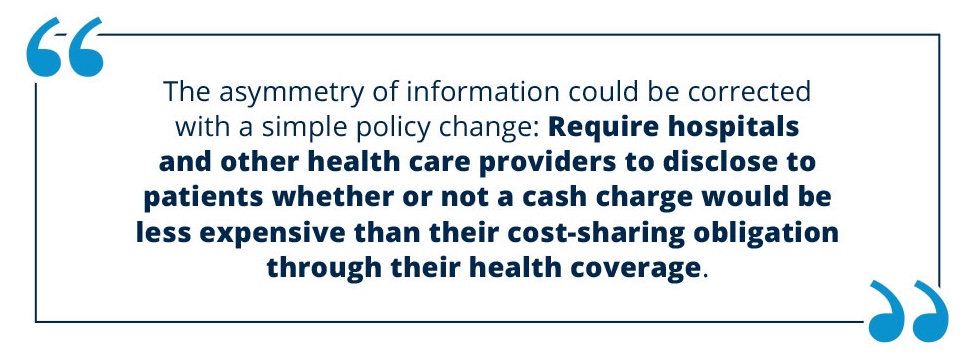

Disclosure of lower cash prices

Price transparency empowers consumers to shop and leads to lower prices.27 While price transparency has long been absent from health care, recent reforms—including a pair of price transparency regulations from the Trump administration and the bipartisan No Surprises Act—have helped shift health care in a more market-oriented direction.28-32 Although these price transparency reforms are a step in the right direction, there is still work to do. In addition to codifying the hospital price transparency and transparency in coverage rules, Congress can go a step further by giving consumers information about how paying cash could help their bottom line.

Some goods and services are priced differently depending on the payment method. For example, many gas stations charge customers lower prices if they pay with cash instead of a credit card.33 This gives consumers the option of choosing a payment method that makes the most sense for them. Health care consumers would benefit from similar knowledge. In some cases, patients could reap substantial savings by paying with cash instead of going through their health coverage. In fact, many hospitals set a lower cash price than what they charge for services paid through an insurance carrier.34

These savings opportunities already exist, but patients with insurance are often kept in the dark. The asymmetry of information could be corrected with a simple policy change: Require hospitals and other health care providers to disclose to patients whether or not a cash charge would be less expensive than their cost-sharing obligation through their health coverage. Congress previously enacted similar prohibitions against gag clauses for pharmaceuticals.35-36 This would extend that commonsense policy to health care more broadly. Under this reform, both providers and consumers would benefit. Providers get upfront payment and avoid the hassle of dealing with the middleman insurer and the patient receives the same care for a lower price.

Association health plans

Association health plans (AHPs) level the playing field for entrepreneurs and businesses by allowing them to band together to purchase health coverage for themselves and their employees at affordable rates.37 In an effort to confront rising health care costs, President Trump dramatically expanded AHPs by allowing these entities to exist primarily for insurance purposes, branch across different industries, pool from different states, and include self-employed entrepreneurs.38 By breaking down these barriers to joining AHPs, the Trump administration’s interpretation freed these entities from being constrained to the more expensive small group market. These changes were estimated to generate benefits of $8 billion annually.39 The impact was substantial as millions of Americans gained access to plans that were, on average, 29 percent more affordable.40-41

Unfortunately, the Trump administration’s rule was challenged in federal court. Although the Trump administration appealed an initial ruling striking down the rule, it remains in legal limbo as the Biden administration has failed to defend the rule.42-43 However, Congress can codify the expansion of AHPs to guarantee that these flexibilities are implemented. Similarly, after the Trump administration issued a rule allowing employers to band together to form Association Retirement Plans, Congress codified those policies through the SECURE Act.44-46

Short-term health plans

For decades, consumers have benefited from the availability of short-term health plans in a wide variety of situations, such as when they are between jobs or waiting to be eligible for Medicare.47 These plans soared in popularity after the enactment of ObamaCare thanks to their comparative affordability, with premiums that are 59 percent less expensive on average.48-49 Even at similar coverage levels, short-term plans tend to be more affordable than what is available on the ObamaCare exchanges.50 And, even though they are exempt from onerous ObamaCare mandates, many short-term plans still offer coverage for things like mental health, substance abuse, maternity services, and more, at more affordable rates.51

Recognizing the value that consumers see in short-term plans, the Trump administration reversed the restrictions from the Obama administration that arbitrarily and dramatically shortened the duration of these popular plans.52-53 An analysis of this change estimated an annual benefit to consumers of $8 billion.54 Since then, consumers in states that fully permit short-term plans have benefited from the increased choice and competition.55 In these states, exchange enrollment is higher, there are more insurers selling exchange plans, and exchange premiums are lower.56 Unfortunately, access to these more affordable and flexible health coverage options is under threat by the Biden administration.57 Congressional action to codify the Trump-era rules would stop the ping-ponging of definitions between presidential administrations and protect the popular coverage options that the Biden administration is threatening to take away.58

The Bottom Line: Health care affordability is within reach.

Health insurance premiums are increasingly unaffordable thanks to ObamaCare. Reforms that stem the tide and put downward pressure on premiums would provide much-needed relief for consumers. Unlike President Obama’s false promise, this proposal does not outlaw existing options.59 If Americans like their current plan, they can keep it. Congress should act to open up new pathways for consumers to select quality coverage options that they can obtain at a lower cost.

References

- Pew Research Center, “Inflation, health costs, partisan cooperation among the nation’s top problems,” Pew Research Center (2023), https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/06/21/inflation-health-costs-partisan-cooperation-among-the-nations-top-problems/.

- Katherine Keisler-Starkey, et al., “Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2022,” U.S. Census Bureau (2023), https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2023/demo/p60-281.html.

- Jennifer Tolbert, et al., “Key facts about the uninsured population,” Kaiser Family Foundation (2022), https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/.

- Alison A. Galbraith et al., “Affordability and access challenges among US subscribers to nongroup insurance plans,” JAMA Health Forum (2022), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2789343.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Individual market premium changes: 2013-2017,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2017), https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/256751/IndividualMarketPremiumChanges.pdf.

- Edmund Haislmaier and Abigail Slagle, “Obamacare has doubled the cost of individual health insurance,” Heritage Foundation (2021), https://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/report/obamacare-has-doubled-the-cost-individual-health-insurance.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Appendix A to 2022 benefit year risk adjustment summary report – HHS risk adjustment program state-specific data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/appendix-2022-benefit-year-risk-adjustment-summary-reporthhs-risk-adjustment-program-state-specific.xlsx.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Out-of-pocket maximum/limit,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/out-of-pocket-maximum-limit/.

- Grocery figures determined by one-year’s worth of groceries at the official USDA cost of food at home for a single male aged 19 – 50 in a moderate-cost food plan. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Official USDA food plans: Cost of food at home at three levels, U.S. average, July 2023,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/media/file/CostofFoodJul2023LowModLib.pdf.

- Patti Domm, “Households are now spending an estimated $5,000 a year on gasoline,” CNBC (2022), https://www.cnbc.com/2022/05/18/households-are-spending-the-equivalent-of-5000-a-year-on-gasoline.html.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Appendix A to 2022 benefit year risk adjustment summary report – HHS risk adjustment program state-specific data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/appendix-2022-benefit-year-risk-adjustment-summary-reporthhs-risk-adjustment-program-state-specific.xlsx.

- Internal Revenue Service et al., “Health reimbursement arrangements and other account-based group health plans,” Federal Register 84(119): 28,888-29,027 (2019), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-06-20/pdf/2019-12571.pdf.

- Department of Health and Human Services et al., “Reforming America’s healthcare system through choice and competition,” U.S Department of Health and Human Services (2018), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Reforming-Americas-Healthcare-System-Through-Choice-and-Competition.pdf.

- Council of Economic Advisors, “Economic report of the President: Together with the annual report of the council of economic advisers,” Executive Office of the President (2020), https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2020-Economic-Report-of-the-President-WHCEA.pdf.

- Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on average plan liability risk scores, disaggregated by state and market. See, e.g., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Appendix A to 2021 benefit year risk adjustment summary report: HHS risk adjustment program state-specific data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2022), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/appendix-2021-benefit-year-risk-adjustment-summary-report-hhs-risk-adjustment-program-state-specific.xlsx.

- Authors’ calculations based upon the results of an actuarial microsimulation model incorporating data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on average plan liability risk scores in the individual market disaggregated by state and on-exchange status, total member months in the individual market, average premiums in the individual market, average actuarial value of plans in the individual market, an assumed 80 percent medical loss ratio, and an assumed $50 per-member-per-month reinsurance program.

- Savings relative to the status quo range from 25 percent with no small group market migration to 34 percent with complete small group market migration.

- An independent actuarial analysis commissioned by the Foundation for Government Accountability by one of the nation’s largest actuarial firms found similar results, with premiums in the new market approximately 24 percent lower than on-exchange premiums.

- This estimate assumes a father (43), mother (41), and two kids (under 14). These ages were selected based on data provided by the U.S. Department of Commerce on the national average ages of fathers and mothers in married-couple families with children.

- Congressional Research Service, “Reinsurance in health insurance,” Congressional Research Service (2017), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10707/3.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Summary report on transitional reinsurance payments and permanent risk adjustment transfers for the 2015 benefit year,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016), https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Premium-Stabilization-Programs/Downloads/June-30-2016-RA-and-RI-Summary-Report-5CR-063016.pdf.

- Namrata K. Uberoi and Edward C. Liu, “The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) transitional reinsurance program,” Congressional Research Service (2017), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44690.pdf.

- Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on total 2015 reinsurance spending and total billable member months in 2015, disaggregated by state. See, e.g., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Appendix A to June 30, 2016 summary report: HHS risk adjustment program state-specific data,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016), https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Premium-Stabilization-Programs/Downloads/Appendix-A-to-June-30-2016-RA-and-RI-Report-5CR-063016.xlsx.

- Namrata K. Uberoi and Edward C. Liu, “The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) transitional reinsurance program,” Congressional Research Service (2017), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44690.pdf.

- Avalere, “Health plans with more restrictive provider networks continue to dominate the exchange market,” Avalere (2018), https://avalere.com/press-releases/health-plans-with-more-restrictive-provider-networks-continue-to-dominate-the-exchange-market.

- Ga. Comp. R. & Regs. r. 120-2-106-.06 (2023), https://rules.sos.ga.gov/GAC/120-2-106-.06?urlRedirected=yes&data=admin&lookingfor=120-2-106-.06.

- Congressional Research Service, “Does price transparency improve market efficiency? Implications of empirical evidence in other markets for the health sector,” Congressional Research Service (2008), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL34101.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicare and Medicaid programs: CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. Price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public,” Federal Register 84(229): 65,524 (2019), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-11-27/pdf/2019-24931.pdf.

- Department of Treasury, “Transparency in coverage,” Federal Register 85(219): 72,158 (2020), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-11-12/pdf/2020-24591.pdf.

- Public Law 116-260 (2020), https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ260/PLAW-116publ260.pdf.

- Public Law 116-260 (2020), https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ260/PLAW-116publ260.pdf.

- Theo Merkel, “Health care price transparency: Achievements, challenges, and next steps,” Paragon Health Institute (2023), https://paragoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Health-Care-Price-Transparency-Merkel-FOR-RELEASE-V1.pdf.

- Penelope Min, “Why do gas stations have a cash and credit price?” The U.S. Sun (2022), https://www.the-sun.com/news/us-news/4966069/gas-station-cash-credit-price/.

- John (Xuefeng) Jiang, et al., “Comparison of US hospital cash prices and commercial negotiated prices for 70 services,” JAMA (2021), http://jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40526.

- Public Law 115-262 (2018), https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ262/PLAW-115publ262.pdf.

- Public Law 115-263 (2018), https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ263/PLAW-115publ263.pdf.

- Jonathan Ingram and Nick Stehle, “Association health plans: Expanding opportunities for small business owners and entrepreneurs,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/association-health-plans-small-business/.

- Executive Order 13813 (2017), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2017-10-17/pdf/2017-22677.pdf.

- The Council of Economic Advisers, “Deregulating health insurance markets: Value to market participants,” Council of Economic Advisers (2019), https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Deregulating-Health-Insurance-Markets-FINAL.pdf.

- Jonathan Ingram and Nick Stehle, “Association Health Plans: Expanding opportunities for small business owners and entrepreneurs,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/association-health-plans-small-business/.

- Hayden Dublois, “Association Health Plans: Affordable health insurance options for small businesses following COVID-19,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/association-health-plans-insurance/.

- Shannon Muchmore, “Judge rules Trump AHP expansion unlawful ‘end-run’ around ACA,” Healthcare Dive (2019), https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/judge-rules-trump-ahp-expansion-unlawful-end-run-around-aca/551601/.

- Shira Stein, “Association health plans in limbo years after Trump rule voided,” Bloomberg Law (2022), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/association-health-plans-in-limbo-years-after-trump-rule-voided.

- Employee Benefits Security Administration, “Definition of ‘employer” under Section 3(5) of ERISA—Association retirement plans and other multiple-employer plans,” Federal Register 84(147): 37,508-37,544 (2019), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-07-31/pdf/2019-16074.pdf.

- Public Law 116-94 (2019), https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ94/PLAW-116publ94.pdf.

- Stephen Miller, “SECURE Act alters 401(k) compliance landscape,” SHRM (2020), https://www.shrm.org/ResourcesAndTools/hr-topics/benefits/Pages/SECURE-Act-alters-401k-compliance-landscape.aspx.

- Michael Greibrok, “The Biden administration’s action on short-term health plans will only harm Americans,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/biden-administrations-action-short-term-health-plans/.

- Anna Wilde Mathews, “Sales of short-term health policies surge,” Wall Street Journal (2016), https://www.wsj.com/articles/sales-of-short-term-health-policies-surge-1460328539.

- Jonathan Ingram, “Short-term plans: Affordable health care options for millions of Americans,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/short-term-plans-affordable-health-care-options-for-millions-of-americans/.

- 50 Chris Pope, “Renewable term health insurance: Better coverage than Obamacare,” Manhattan Institute (2019), https://media4.manhattan-institute.org/sites/default/files/R-0519-CP.pdf.

- 51 Ibid.

- 52 Internal Revenue Service et al., “Excepted benefits; lifetime and annual limits; and short-term, limited-duration insurance,” Federal Register 81(210): 75,316-75,327 (2016), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-10-31/pdf/2016-26162.pdf.

- 53 Internal Revenue Service et al., “Short-term limited-duration insurance,” Federal Register 83(150): 38,212-38,243 (2018), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-08-03/pdf/2018-16568.pdf.

- 54 The Council of Economic Advisers, “Deregulating health insurance markets: Value to market participants,” Council of Economic Advisers (2019), https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Deregulating-Health-Insurance-Markets-FINAL.pdf.

- 55 Brian Blase, “Short-term health plans, long-term benefits: States that allow short-term coverage have stronger health insurance markets,” Paragon Health Institute (2023), https://paragoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Short-Term-Insurance-Long-Term-Benefits_FOR-RELEASE-V3.pdf.

- 56 Ibid.

- 57 Internal Revenue Service et al., “Short-term, limited-duration insurance; independent, noncoordinated excepted benefits coverage; level-funded plan arrangements; and tax treatment of certain accident and health insurance,” Federal Register 88(132): 44,596-44,658 (2023), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-07-12/pdf/2023-14238.pdf.

- 58 Michael Greibrok, “The Biden administration’s action on short-term health plans will only harm Americans,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/biden-administrations-action-short-term-health-plans/.

- 59 Angie Drobnic Holan, “Lie of the year: ‘If you like your health care plan, you can keep it,’” PolitiFact (2013), https://www.politifact.com/article/2013/dec/12/lie-year-if-you-like-your-health-care-plan-keep-it/.