Married to a Myth: Debunking the “Marriage Penalty” in Food Stamps

KEY FINDINGS

- Food stamp benefits are determined by household income—marital status does not affect benefits.

- Marriage does not change work requirements for able-bodied enrollees.

- Cohabitation—not marriage—affects benefits. And cohabitation can both decrease or increase monthly food stamp benefits depending on changes in a household’s income.

- There is no ‘marriage penalty’—but there is fraud.

Background:

Marriage matters. It is a stronger indicator for social mobility than the quality of schools, race, or even income inequality.1

Married couples work more, earn more money, and remain in dependency less.2-14 They live longer, healthier, and more fulfilling lives.15-16 Married couples commit less crime and create safer neighborhoods.17-21 And they raise children more likely to be healthier and happier and less likely to be abused, drop out of school, use drugs, suffer mental illness, commit suicide, or stay in dependency.22-25

The list goes on and on. But at the same time, the number of unmarried Americans living together—or cohabitating—has tripled in recent decades.26

Armed with this knowledge, many policymakers understandably want welfare programs to increase incentives to get married and to eliminate disincentives to marriage.

But that desire has fanned the flames of an unfortunate myth in welfare reform debates: a “marriage penalty” in welfare programs. As Congress negotiates a new Farm Bill and considers reforms to food stamps, the existence of a “marriage penalty” in that program warrants renewed attention.

In short, there is no “marriage penalty” in food stamps.

And it is especially critical for policymakers to understand that some of the same researchers who rightly point to the power of marriage play a role in perpetuating the myth of a “marriage penalty.”27-29

How are food stamp benefits calculated?

State agencies determine monthly food stamp benefit levels under rules set out in federal law.30 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) determines the baseline cost to a typical American family of purchasing food for a basic nutritious diet based on food prices, consumption patterns, and dietary guidance, among other factors.31 This baseline is called a “thrifty food plan.”32

Put simply, the purpose of the food stamp program is to supplement the food spending of low-income households (those with incomes lower than 130 percent of the federal poverty level) enough to close the gap between what they can afford and the value of the Thrifty Food Plan, as set by the USDA.33 This explains why the program’s formal name is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Unlike many other government programs, food stamp benefits are distributed to households rather than individuals. What constitutes a “household” matters in any conversation about a supposed “marriage penalty” and is addressed below.

For now, it is important to note that a household’s income is what determines the household’s food stamp benefit.

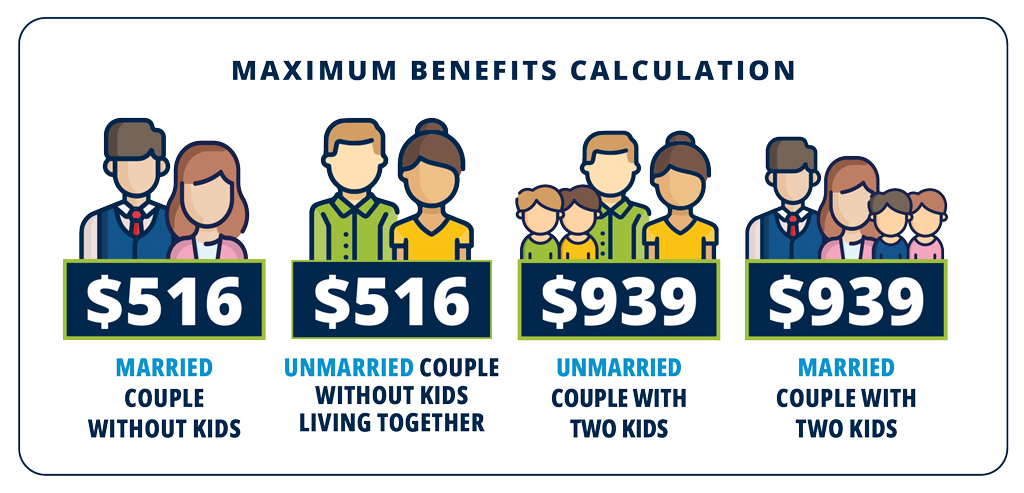

How does it work? State agencies begin with whatever the maximum monthly benefit is. This is the amount a household would receive if it reports no income at all. For example, in every state but Alaska and Hawaii, $740 is the maximum monthly benefit for a household with three individuals in 2023.34 For a household with four or five individuals, the maximum monthly benefit is $939 and $1,116 per month, respectively.35

Starting with this maximum monthly benefit, state agencies calculate benefit amounts by subtracting 30 percent of the household’s monthly gross income (along with exclusions and deductions, like a 20 percent deduction of all earned income).36-37 In 2023, the average monthly benefit for households is $485.30.38

Marital status does not affect food stamp benefits

How does a couple’s marital status affect benefit calculation? The answer is simple: It does not. Households, not couples—married or not—are the relevant units in food stamps.

To clarify, there is more than one way for an individual or group of individuals to be treated as a household for the purpose of determining food stamp eligibility. But in the context of a couple—married or unmarried—and how they are categorized, two definitions matter.

First, federal law specifically considers spouses who live together, parents and their children 21 years of age or younger who live together, and children (excluding foster children) under 18 years of age who live with and are “under the parental control of a person other than their parent together with the person exercising parental control” to constitute a “household” expected to “customarily purchase and prepare meals together for home consumption even if they do not do so.”39

But federal law also defines a household as any “individuals who live together in the same residence and who purchase and prepare food together” or “an individual who lives alone or who, while living with others, customarily purchases food and prepares meals for home consumption separate and apart from the others.”40

Marriage does not affect whether a couple is treated as a household or not.

But does it affect benefits? No. Benefits are determined by household size (because size determines the applicable federal poverty level) and household income.

In other words, an unmarried couple living together receiving food stamps who get married but do not have any other changes in income will not see their food stamp benefits change at all. The marital status of the individuals inside a household is irrelevant.

In the reverse, if a couple living separately decides to move in together but not get married, their benefits may change because the size of their household has changed and their incomes will be combined for benefit calculation.

There is no “marriage penalty.” Cohabitation, rather than marriage, can affect benefits because it changes the size of the household and can change the income of the household.

For example, take Adam and Amanda, a young couple considering marriage and not currently living together. Amanda works part time, makes an adjusted $18,000 per year after her exclusions and deductions (putting her close to 130 percent of the federal poverty level for a household of one), and receives the minimum food stamp benefit: $23 per month.41 Adam does not work. Because he reports no income, he earns the maximum monthly benefit for a household of one: $231.42

What if Adam and Amanda move in together but choose not to get married? First, they will become a household of two. 130 percent of the federal poverty level for a household of two is more than $25,000 per year compared to less than $19,000 for a household of one.43 Because their income does not change but their household size grows, their benefit will actually increase.

What if they move in together but choose to get married? Their relationship with each other may look different but their relationship with the food stamp program will be exactly the same as it was without marriage. Their benefit will still increase by the same amount.

Cohabitation—not marriage—affects benefits. And cohabitation can decrease or increase monthly food stamp benefits. It all depends on how the household’s total income changes.

If they choose to have children, their household will become bigger and income limits will increase, too. For example, 130 percent of the federal poverty level for a household of three is $32,318.44 With no change in income, their benefits will increase again.

This is not a “penalty.” An eligibility process that calculates benefits based on a sliding scale determined by a household’s income is the defining characteristic of any means-tested program.

The real issue is not any kind of “marriage penalty.” It is program integrity.

Fraud is not a myth

Based on how benefits are set under federal law, there is an incentive for individuals— particularly those in two-income couples—to not reveal their cohabitation or marriage when they apply for food stamp benefits. Examples of this form of fraud proliferate.45-46

In theory, couples who are already cohabitating may choose not to marry to avoid raising red flags in order to artificially maintain multiple households in the food stamp program. To the extent this is happening, these individuals are not eligible for the benefits they are receiving and are committing fraud.

Imagining—let alone fixing—some kind of “marriage penalty” is not the solution to this problem. The solution is more robust data cross-checks and investigations to ensure that program resources are reserved for the truly needy.

And, if policymakers are interested in privileging married couples over couples who cohabitate, strengthening program integrity, ending fraud, and promoting work requirements are the ways to do it.

Marriage does not change work requirements for able-bodied enrollees

Marriage also does not affect work requirements. There are two different work requirements in food stamps: a work requirement for able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) under the age of 50 and a general work requirement that applies to a broader category of able-bodied adults.47

These two work requirements apply to slightly different populations. But neither is affected by marriage.

The ABAWD work requirement applies to able-bodied adults under the age of 50 who do not have children. A person subject to the ABAWD work requirement can comply by working, training, or volunteering for 20 hours per week.48

Marriage does not change applicability or exemptions. If a person is physically or mentally unable to work, over the age of 50, pregnant, or living in a household with a dependent, they are exempt from this requirement.49 An ABAWD’s requirements under the program standards are not affected by marriage.

If a person subject to the ABAWD work requirement moves in with someone else with no dependents, the person is still subject to the ABAWD work requirement whether they are married or not. And if a person subject to the ABAWD work requirement moves in with someone who does have a dependent, the person also becomes exempt, whether they are married or not.

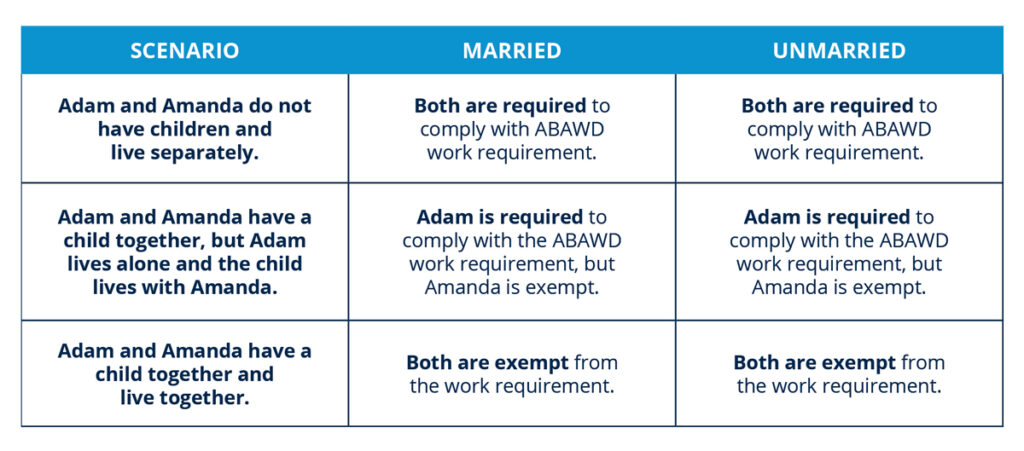

For example, if Adam and Amanda are both able-bodied 33-year-olds who receive food stamps and live separately with no dependents, they are both subject to the ABAWD work requirement. If they have a child together but the child lives with Amanda and Adam continues to live alone, Adam is subject to the ABAWD work requirement and Amanda is exempt. If Adam and Amanda get married but continue to live apart, Adam is still subject to the ABAWD work requirement and Amanda is still exempt. If they move in together with their child in the home, both are exempt from the work requirement whether they are married or not.

The general work requirement is more inclusive than the ABAWD requirement. It requires able-bodied adults up to age 59, including those with children age six and older, who do not already work 30 hours per week to participate in a state’s employment and training (E&T) program if the state assigns them to one.50

Still, marriage does not change an enrollee’s obligations under the general work requirement. For example, if Gary and Gabriela are able-bodied 55-year-olds who receive food stamps and live together with a 15-year-old daughter, and Gary and Gabriela are assigned to an E&T program under the general work requirement, their responsibilities are the same whether they are married or not.51

It is possible for one individual’s compliance with a work requirement to have an effect on the rest of the household’s benefits, but marriage does not play any role in this. State agencies designate a member of every household receiving food stamps as the “head of household.”52 If the agency disqualifies the head of household for failure to comply with the general work requirement, the state agency may also make the other members of the household ineligible for a period of no more than 180 days.53 Yet this is true whether members of the household are married or not.

THE BOTTOM LINE: Lawmakers should recognize the “marriage penalty” in food stamps for the myth that it is and focus on strengthening work requirements and program integrity.

Work requirements simply do not penalize marriage, they promote self-sufficiency and social mobility. People who are married and working regularly have higher incomes, commit less crime, and live longer than those who are not, and their children do too. Strengthening food stamp program integrity and promoting commonsense work requirements are the best ways to help people out of dependency, not promoting a myth that discourages both work and marriage.

REFERENCES

1 Raj Chetty et al., “Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2014), https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju022.

2 Robert Lerman, “Effects of marriage on family economic well-being,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2002), https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/effects-marriage-family-economic-well-being.

3 Robert Lerman, “Should government promote healthy marriages?,” Urban Institute (2002), https://webarchive.urban.org/publications/310499.html.

4 Julia Carpenter, “Moving in together doesn’t match the financial benefits of marriage, but why?” Wall Street Journal (2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/moving-in-together-doesnt-match-the-financial-benefits-of.marriage-but-why-11667761626.

5 Richard Fry and D’Vera Cohn, “Women, men and the new economics of marriage,” Pew Research Center (2010), https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2010/01/19/women-men-and-the-new-economics-of-marriage.

6 Adam Blandin et al., “Marriage and work among prime-age men,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond (2023), https://doi.org/10.21144/wp23-02.

7 Robert Lerman, “Marriage and the economic well-being of families with children,” Urban Institute (2002), https://webarchive.urban.org/UploadedPDF/410541_LitReview.pdf.

8 W. Bradford Wilcox, “Don’t be a bachelor: Why married men work harder, smarter and make more money,” Washington Post (2015), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/inspired-life/wp/2015/04/02/dont-be-a.bachelor-why-married-men-work-harder-and-smarter-and-make-more-money.

9 Sanders Korenman and David Neumark, “Does marriage really make men more productive?,” The Journal of Human Resources (1991), https://www.jstor.org/stable/145924.

10 U.S. Joint Economic Committee, “The demise of the happy two-parent home,” U.S. Joint Economic Committee (2020), https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2020/7/the-demise-of-the-happy-two-parent.home.

11 S.L. Mintz, “Why do married men earn more than single guys doing the same job?,” CBS News (2011), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/why-do-married-men-earn-more-than-single-guys-doing-the-same-job.

12 Isabel Sawhill and Ron Haskins, “Work and marriage: The way to end poverty and welfare,” The Brookings Institution (2003), https://www.brookings.edu/research/work-and-marriage-the-way-to-end-poverty-and-welfare.

13 W. Bradford Wilcox, “Marriage is an important tool in the fight against poverty,” Institute for Family Studies (2016), https://ifstudies.org/blog/marriage-is-an-important-tool-in-the-fight-against-poverty.

14 Maggie Gallagher, “Why marriage is good for you,” City Journal (2000), https://www.city.journal.org/article/why-marriage-is-good-for-you.

15 Ibid.

16 Office of Family Assistance, “Healthy marriage and relationship education for adults,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/healthy-marriage-responsible.fatherhood/healthy-marriage.

17 David Ribar, “Why marriage matters for child wellbeing,” Future of Children (2015), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1079374.pdf.

18 Torbjørn Skardhamar et al., “Does marriage reduce crime?,” Crime and Justice Volume 44 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1086/681557.

19 Robert Sampson et al., “Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within-individual causal effects,” Criminology Volume 44 (2006), https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/sampson/files/2006_criminology_laubwimer_1.pdf.

20 Delphine Theobald and David Farrington, “Why do the crime-reducing effects of marriage vary with age?,” The British Journal of Criminology (2011), https://www.jstor.org/stable/23640341.

21 W. Bradford Wilcox and Chris Bullivant, “The benefits of marriage shouldn’t only be for elites,” Institute for Family Studies (2022), https://ifstudies.org/blog/the-benefits-of-marriage-shouldnt-only-be-for-elites.

22 Maggie Gallagher, “Why marriage is good for you,” City Journal (2000), https://www.city.

journal.org/article/why-marriage-is-good-for-you.

23 AEI-Brookings Working Group on Childhood in the United States, “Children first: Why family structure and stability matter for children,” Institute for Family Studies (2022), https://ifstudies.org/blog/children-first-why.family-structure-and-stability-matter-for-children.

24 Kimberly Howard and Richard Reeves, “The marriage effect: Money or parenting?,” The Brookings Institution (2014), https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-marriage-effect-money-or-parenting.

25 U.S. Joint Economic Committee, “The demise of the happy two-parent home,” U.S. Joint Economic Committee (2020), https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2020/7/the-demise-of-the-happy-two-parent.home.

26 United States Census Bureau, “Cohabiting Partners Older, More Racially Diverse, More Educated, Higher Earners”, United Staes Department of Labor (2019), https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/09/unmarried.

partners-more-diverse-than-20-years-ago.html.

27 Robert Rector, “Marriage: America’s greatest weapon against child poverty,” The Heritage Foundation (2012),

28 Benjamin Paris and Jamie Hall, “How welfare programs discourage marriage: The case of Pre-K education subsidies,” The Heritage Foundation (2023), https://www.heritage.org/welfare/report/how-welfare-programs-discourage-marriage-the-case-pre-k-education-subsidies.

29 Robert Rector and Jamie Hall, “Food stamp reform bill requires work for only 20 percent of work-capable adults,” The Heritage Foundation (2018), https://www.heritage.org/hunger-and-food-programs/report/food.

stamp-reform-bill-requires-work-only-20-percent-work-capable.

30 7 USCS, Ch. 51. (2021), https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title7/chapter51&edition=prelim.

31 7 USCS § 2012(u) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021-title7chap51-sec2012.pdf.

32 Ibid.

33 7 USCS § 2014 (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021-title7/chap51-sec2014.pdf.

34 Food and Nutrition Services, “SNAP – Fiscal year 2023 cost-of-living adjustments,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-fy-2023-cola/adjustments.pdf#page=3.

35 Ibid.

36 7 USCS § 2017 (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021-title7/chap51-sec2017.pdf.

37 7 USCS § 2014 (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021-title7/chap51-sec2014.pdf.

38 Food and Nutrition Services, “Persons, households, benefits, and average monthly benefit per person and household,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource/34SNAPmonthly-4.pdf.

39 7 USCS § 2012(m) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021-title7-chap51-sec2012.pdf.

40 Ibid.

41 The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “2023 poverty guidelines: 48 contiguous states (all states except Alaska and Hawaii),” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023),

2023.pdf.

42 Food and Nutrition Services, “SNAP – Fiscal year 2023 cost-of-living adjustments,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-fy-2023-cola-adjustments.pdf#page=3.

43 The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “2023 poverty guidelines: 48 contiguous states (all states except Alaska and Hawaii),” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023),

2023.pdf.

44 Ibid.

45 United States Attorney’s Office District of Maryland, “Baltimore woman pleads guilty to food stamp and Medicaid fraud,” U.S. Department of Justice (2015), https://www.justice.gov/usao-md/pr/baltimore-woman-pleads-guilty-food-stamp-and-medicaid-fraud.

46 United States Attorney’s Office District of New Hampshire, “Nashua woman pleads guilty to fraudulently obtaining food stamps and Medicaid benefits,” U.S. Department of Justice (2022), https://www.justice.gov/usao/nh/pr/nashua-woman-pleads-guilty-fraudulently-obtaining-food-stamps-and-medicaid-benefits.

47 FGA, “Myth vs. fact: Mandatory Employment and Training under the general work requirement in food stamps,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/additional-research/myth-vs-fact-mandatory-employment-and-training-food-stamps.

48 7 U.S.C. § 2015(d) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2021-title7/USCODE-2021-title7.chap51-sec2015.

49 Ibid.

50 Food and Nutrition Service, “Clarifications on work requirements, ABAWDs, and E&T,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2018), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/clarifications-work-requirements-abawds-and-et.

51 7 U.S.C. § 2015(d) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2021-title7/USCODE-2021-title7/chap51-sec2015.

52 7 USCS § 2015(d)(D)(V)(I) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2021-title7/USCODE-2021.title7-chap51-sec2015.

53 7 USCS § 2015(d)(B) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2021-title7/USCODE-2021-title7chap51-sec2015.