Show Me the Zuckerbucks: Outside Money Infiltrated Missouri’s 2020 Election

- BY FGA

KEY FINDINGS

THE BOTTOM LINE:

Missouri should prohibit government election offices from accepting funding from private individuals, non-profits, and special interest groups.

Overview

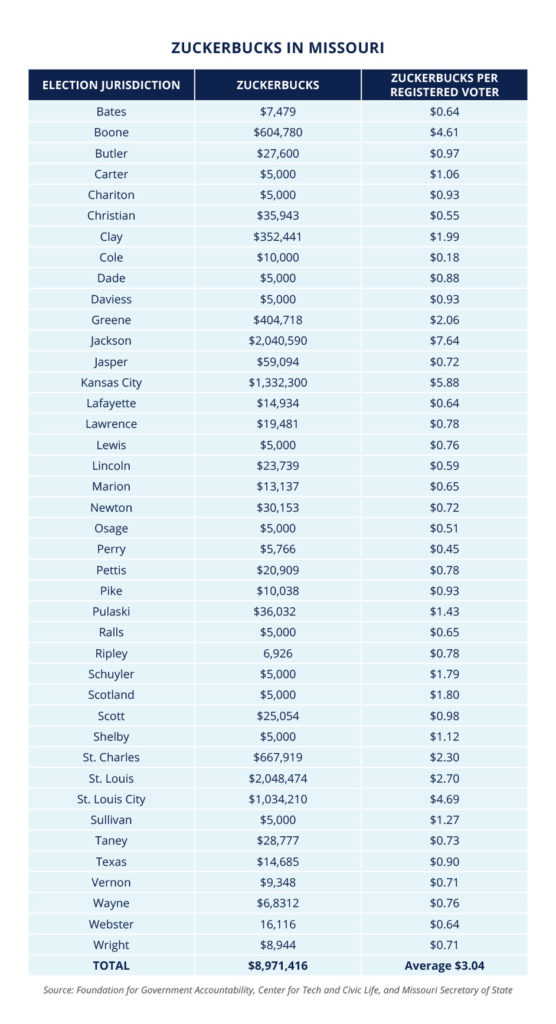

During the 2020 election, the Center for Tech and Civic Life (CTCL), a non-profit run by a former Obama Foundation fellow, used the $400 million it received from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, to distribute thousands of “COVID-19 response grants” to election offices around the country.1–2–3 These grants, or Zuckerbucks, found their way into more than a third of Missouri’s local election offices—to the tune of nearly $9 million.4–5 And this does not even include a separate $1.1 million grant the Missouri Secretary of State’s Office received from the Center for Election Innovation and Research—another Zuckerberg-funded group.6–7

Zuckerbucks reached across Missouri but grant awards favored Democrats

Just as they did in the battleground state of Pennsylvania, Zuckerbucks followed Democrats.8 All Biden-carried counties received Zuckerbucks, while less than half of the counties won by President Trump were grant recipients.9 But the disparity in grant award amounts is even more alarming.

Zuckerbucks awards varied widely across the state and ranged from $5,000, the minimum grant amount, to more than $2 million.10 Eleven of the counties carried by President Trump received only the $5,000 minimum whereas the lowest amount received by a Biden-carried jurisdiction was 120 times larger.11 In fact, Biden-carried counties averaged a grant award of nearly $1.3 million.12 By comparison, the average award for a Trump-carried county was less than $107,000.13

But grant amounts did not necessarily scale with population size. Instead, generosity skewed in favor of jurisdictions with greater support for the Democrat ticket. The average grant amount per registered voter for a Biden-carried jurisdiction was more than 50 percent larger than the average for Trump-carried counties.14

Looking at the distribution of Zuckerbucks by state senate district shows similar patterns. The 75 counties that did not receive Zuckerbucks are all represented by Republicans. And across the 34 senate districts, the only three counties that were completely free of Zuckerbucks are all represented by Republicans.15 Counties represented by at least one Democrat senator received 76 percent of Zuckerbucks.16

Zuckerbucks influenced the election

On average, Missouri counties that received Zuckerbucks saw an increase in the Democrat presidential candidate’s share of the vote between 2016 and 2020.17 For example, although President Trump held on to win Jackson County, the margin of victory shrank dramatically. The Kansas City suburb and beneficiary of the second largest grant in the state saw support for the Democrat candidate increase by more than 20,000 votes.18 President Trump went from carrying the county by more than 12 points in 2016 to about four points.19 Similarly, St. Charles County, which received the second-largest grant among Trump-carried counties, was also a candidate for boosting Democrat turnout.

MISSOURI’S 2ND CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT

Of the three counties that comprise the 2nd Congressional District—a top target for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee—St. Louis County and St. Charles County received Zuckerbucks.20 In fact, these two counties benefited from some of the most generous awards to Missouri jurisdictions. The Republican incumbent, Rep. Ann Wagner, earned fewer votes in both counties than she did in 2016.21 By contrast, Wagner’s opponent saw Democrat votes increase by 32 percent.22 This combination of fewer votes for Wagner and the surge in opponent votes led to one of the closest contests during Wagner’s career.

In Jefferson County, which did not receive Zuckerbucks, the increase in votes in the congressional race was more evenly distributed among the two major-party candidates.23 Wagner increased her vote count in Jefferson County and, unlike in Zuckerbucks-receiving counties, had a margin of victory comparable to that of 2016.

How was the money spent?

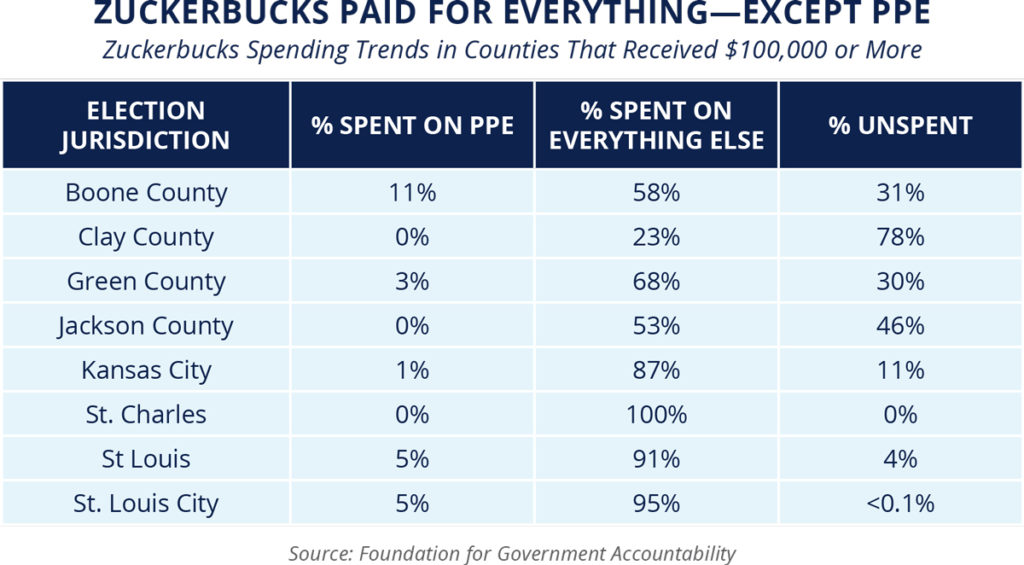

Personal protective equipment (PPE) was supposed to be a primary expenditure for the COVID-19 response grants.24 In practice, however, grant spending on PPE was light, less than five percent of expenditures.25 But counties found ways to spend the money, including spending nearly a quarter of a million dollars on “non-partisan voter education.” More than half of that spending came from Jackson County which requested $1.5 million for outreach and education campaigns.26 It ended up spending much less.

While most grant reports are light on the details of what exactly constitutes “non-partisan voter education,” some counties were more detailed in their reporting. Boone County, which categorized nearly $15,000 as voter education, gave a specific example.27 The report describes how those funds were used to produce a music video and radio spot with local rap artists.28–29

Most of the money appears to have been spent on updating equipment—not necessarily pandemic-related—and providing bonus pay to poll workers. Roughly a third of Zuckerbucks went to procure new election equipment.30 Another third was used to pay poll workers and volunteers.31

But more than $1.8 million—20 percent of the total allotted to Missouri—was not even spent during the 2020 election.32 In Jackson County, nearly $1 million went unspent.33

Although the COVID-19 Response Grant program was purportedly launched to provide funding for the 2020 election, jurisdictions that had unspent grant funds were given an opportunity to continue spending through June 2021.34 Election offices that received an extension were required to submit a second grant report.35 But some counties that had small balances remaining, like Butler and Pike counties, were told, “[u]pon review, CTCL has approved your report and has decided to grant the remaining balance, to be applied towards future election administration expenses. You will not be required to report on the remaining balance.”36–37

Counties with larger balances were still required to file extension reports. Preliminary data suggests election offices largely found ways to spend their remaining funds in the six months after the election.38 More than $1.3 million was spent during the extension period and only about 10 percent of the extension balances were returned.39

Bottom line:

Missouri should prohibit government election offices from accepting funding from private individuals, non-profits, and special interest groups. And lawmakers should require any remaining funds to be returned.

Missouri’s elections should be safeguarded from outside influence. Allowing private funding of government offices could result in corporations and special interests having more influence in election outcomes than voters. This undermines the integrity of the process and erodes voter confidence. To restore trust in Missouri elections, legislators should prohibit government election offices from accepting or spending funding from private individuals, outside groups, and non-profits.