Waivers Gone Wild: Congress Must Crack Down On Food Stamp Loopholes

KEY FINDINGS

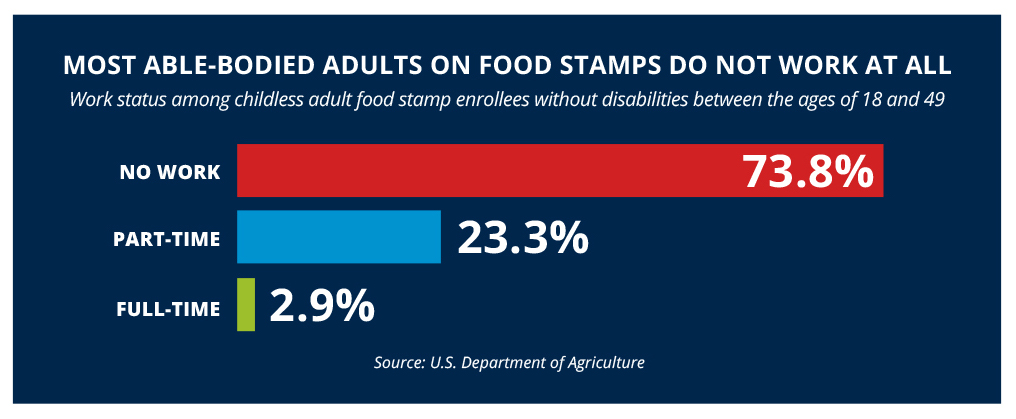

- Four million able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDS) are on food stamps, with three-quarters of ABAWDS not working at all.

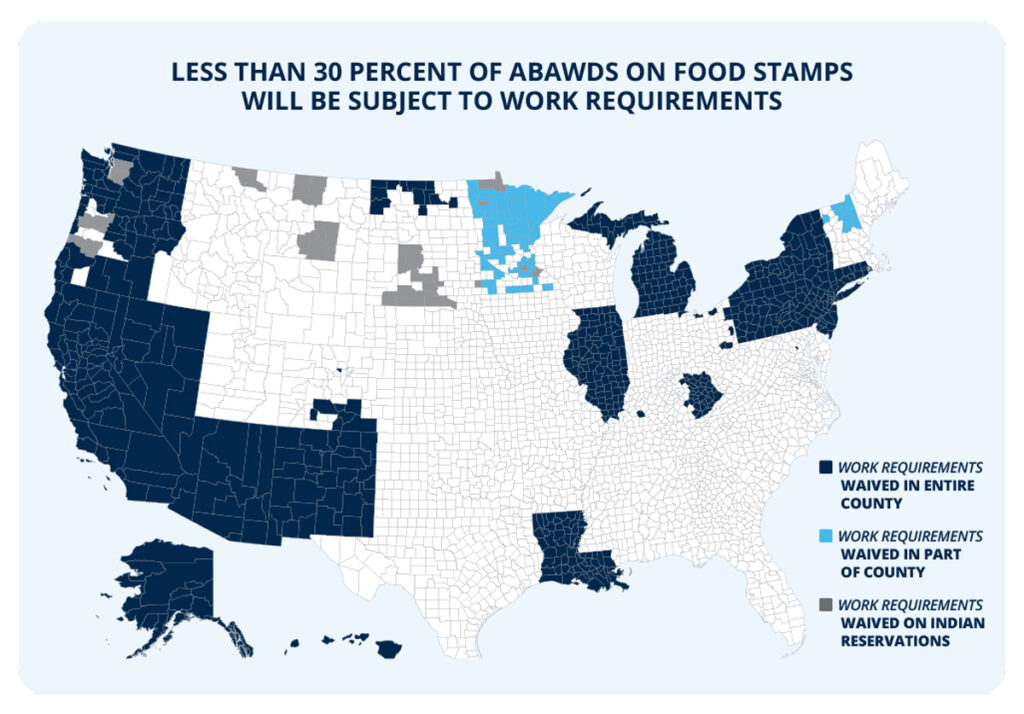

- When work requirements go back into effect in July 2023, less than 30 percent of ABAWDS will be subject to work requirements due to waivers and exemptions.

- States have used loopholes and gimmicks to waive work requirements enacted by congress, even in areas with record-low unemployment.

- Less than three percent of counties with waivers have unemployment rates at or above 10 percent—the statutory threshold—and 75 percent are at “full employment.”

- With nearly 10 million open jobs—1.7 open jobs for every jobseeker—America needs more able-bodied adults to move from welfare to work.

Overview

Despite nearly 10 million open jobs sitting unfilled nationwide, the number of able-bodied adults receiving food stamps remains near record-high levels.1 Indeed, roughly four million ABAWDs are enrolled in the program—near a record high.2-4

Federal law requires ABAWDs to work, train, or volunteer at least part time to maintain program eligibility.5 These rules apply to non-pregnant adults, between the ages of 18 and 49, who are mentally and physically fit for employment, and have no dependent children at home.6

Unfortunately, the ABAWD work requirement has been suspended since the public health emergency began, causing a massive uptick in enrollment for many states.7 And while the public health emergency has finally ended and work requirements should return in July 2023, many states are still gaming the system to maximize enrollment.

States use loopholes and gimmicks to bypass work requirements

States have long used loopholes and gimmicks to waive commonsense work requirements in as many jurisdictions as possible. Congress intended for these waivers to be limited in nature, meant only for areas with unemployment rates above 10 percent, or that otherwise lacked suitable job opportunities for able-bodied adults.

But in the final days of the Clinton administration, bureaucrats at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) issued new rules creating loopholes that allowed states to waive work requirements for millions of able-bodied adults, even during periods of economic growth.9-10 Three of the largest loopholes have allowed states to gerrymander areas in order to waive work requirements in as many jurisdictions as possible, rely on outdated data to justify waivers, and waive work requirements in areas with objectively low unemployment, as long as it is slightly above the national average.11-12 Making matters worse, the Obama administration actively pressured states into waiving the work requirement to keep as many able-bodied adults trapped in dependency as possible.13 The Biden administration is continuing that policy, with USDA “highly encourag[ing]” states to seek waivers and use exemptions to bypass the work requirement.14 States report that they expect at least 70 percent of ABAWDs to be exempt from the work requirement even after the nationwide suspension ends.15

Even before the pandemic, these loopholes and gimmicks left most able-bodied adults on food stamps on the sidelines. A whopping 74 percent of ABAWDs did not work at all prior to the pandemic, while less than three percent worked full time.16

Work requirements are wiped out by gerrymandering

Although federal law allows states to request waivers in specific areas with high unemployment, current rules allow states to combine counties, cities, and other jurisdictions together to form a single “area” for waiver purposes.17-19 This loophole has led states to abuse this flexibility by gerrymandering areas together to waive the work requirement for as many able-bodied adults as possible. Officials from multiple states have admitted that they request “waivers in as many parts of the state as possible” as a way to “minimize the areas” subject to the work requirement.20 States also often rely on software or analyses prepared by left-wing advocacy groups, including the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), which are specifically designed to maximize the number of people states can exempt from the work requirement through waivers.21

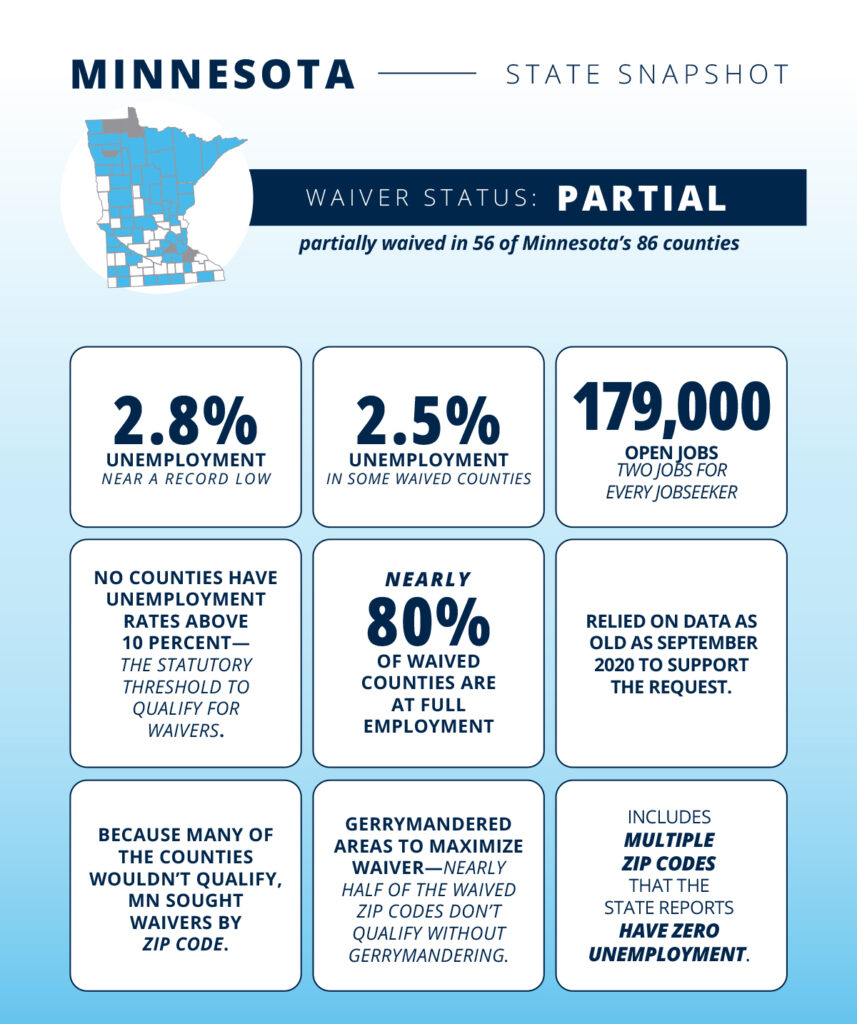

In Minnesota, for example, state officials sought waivers for 35 different gerrymandered “regions” of nearly 165 ZIP Codes.22 But nearly half of those ZIP Codes did not independently qualify and could only be waived if gerrymandered with other areas.23 State officials even reported that multiple waived jurisdictions had no unemployment.24

In Oregon, state officials gerrymandered a group of 19 counties together for waiver purposes, despite the fact that just seven of those counties independently qualified due to their unemployment levels.25 State officials reported unemployment rates as low as 3.2 percent—well below the national average at the time—in some waived counties during their chosen lookback period.26

Similarly, Washington combined 37 of its 39 counties into a single “area” for waiver purposes.27 This grouping suggests that Washington state has just two economic regions: two—but not all three—of the counties that make up the Seattle metropolitan area and the rest of the state. Nearly half of the counties in this gerrymandered area would not independently qualify for waivers.28

States manipulate old data to get new waivers

Federal law limits waivers to areas that have unemployment rates above 10 percent or otherwise do not have a sufficient number of jobs.29 This reflects a present-tense requirement, indicating that USDA may only waive work requirements based on current economic conditions. But Clinton- era regulations and Obama-era guidance reinstituted by the Biden administration created an extended lookback period, allowing states to continue waiving work requirements long after any economic crisis has passed.30-31

Under those rules, states can use unemployment data dating back as far as the period used to calculate labor surplus areas.32 For fiscal year 2023, the lookback period could date as far back as January 2020, allowing states to use data from three years ago—during the height of the pandemic and government-imposed lockdowns—to support waiver requests, even when that data has no connection to current economic conditions.33

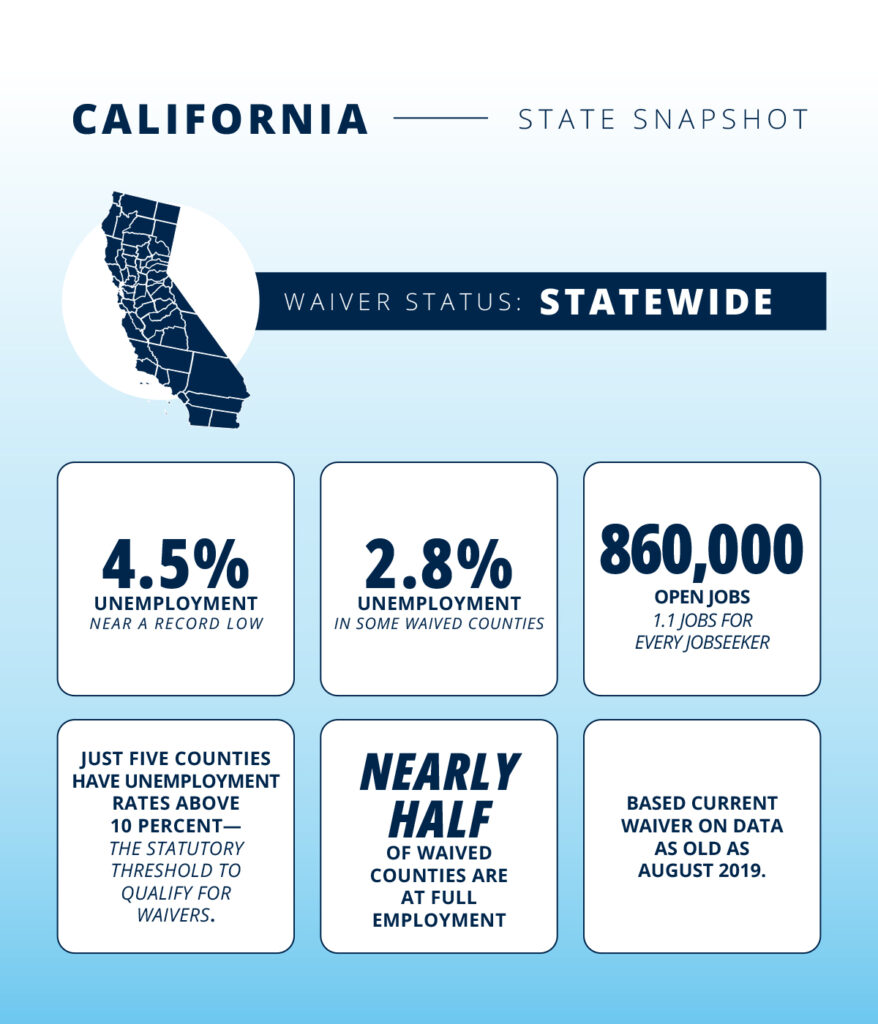

California wins the prize for using the oldest data, relying on data going as far back as August 2019—45 months ago.34 But all states with active waivers relied on data from the peak of the pandemic in 2020, with many reaching as far back as the periods associated with government- imposed lockdowns in the early spring.35 Some states, such as New Hampshire, even cherry- picked different lookback periods for gerrymandered groups in the same waiver request.36

To put this in perspective, states are successfully using data from a time when the national unemployment rate was 14.7 percent to justify waivers when the unemployment rate sits a near-record-low 3.4 percent.37

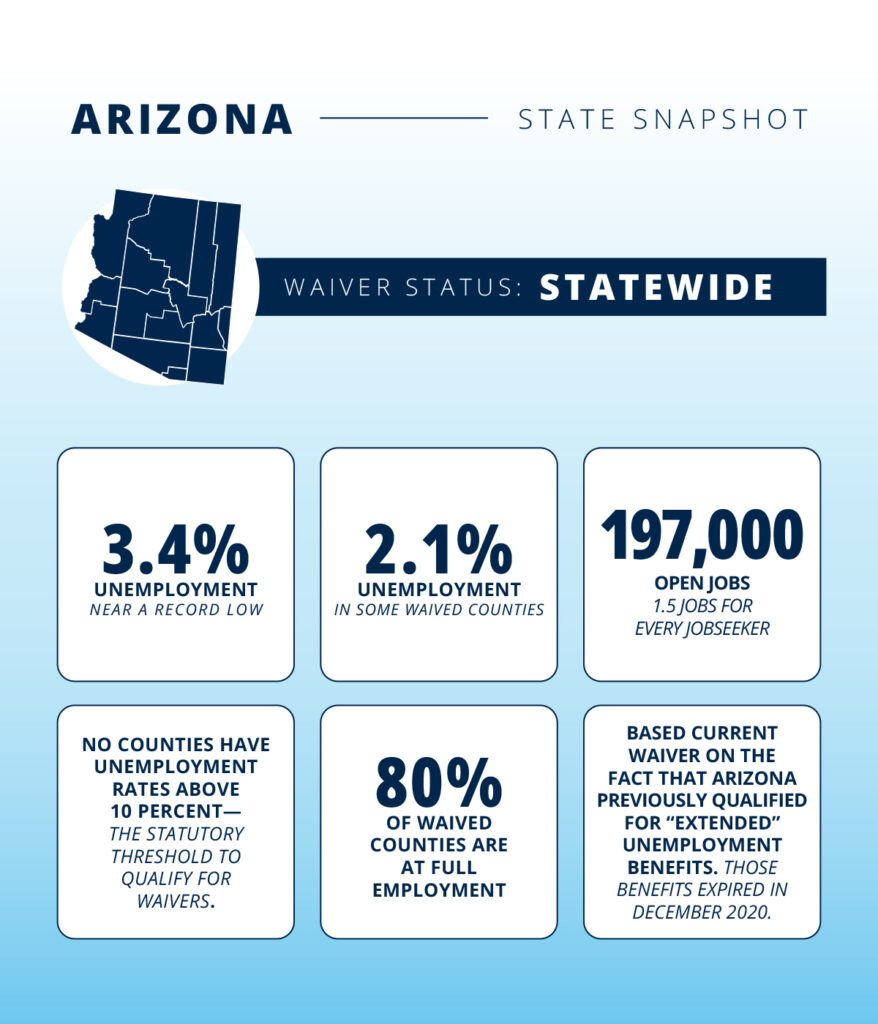

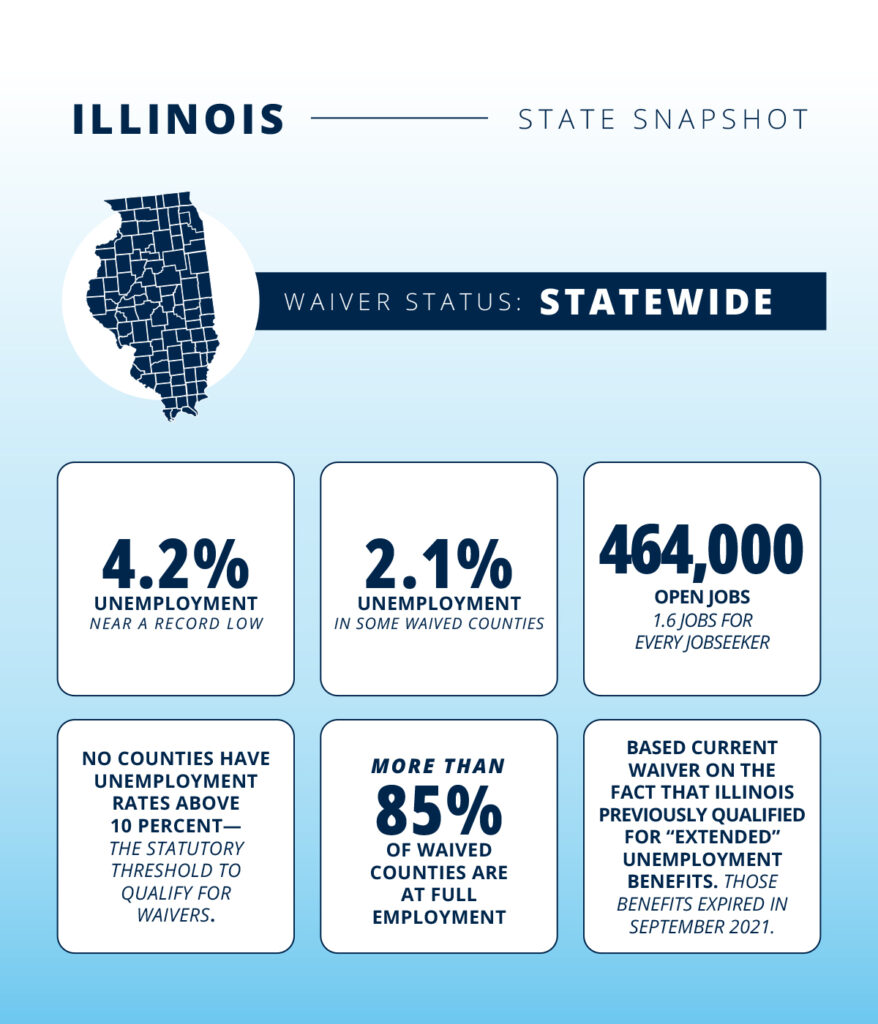

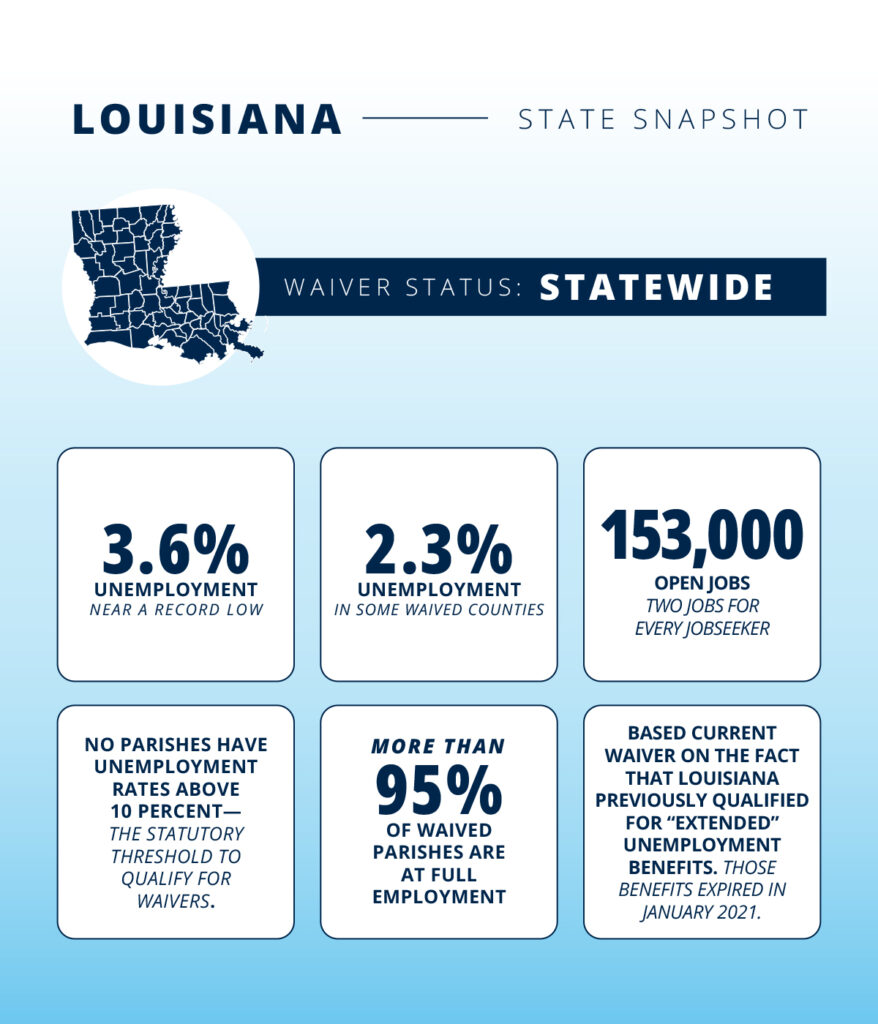

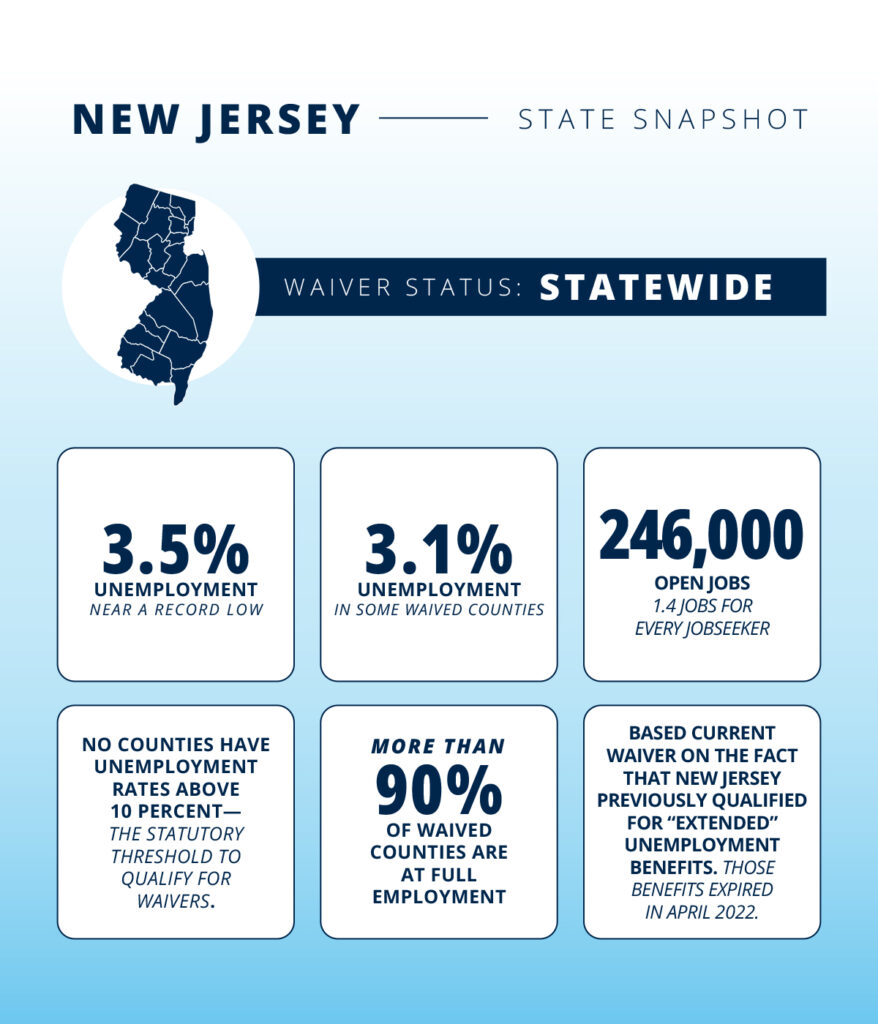

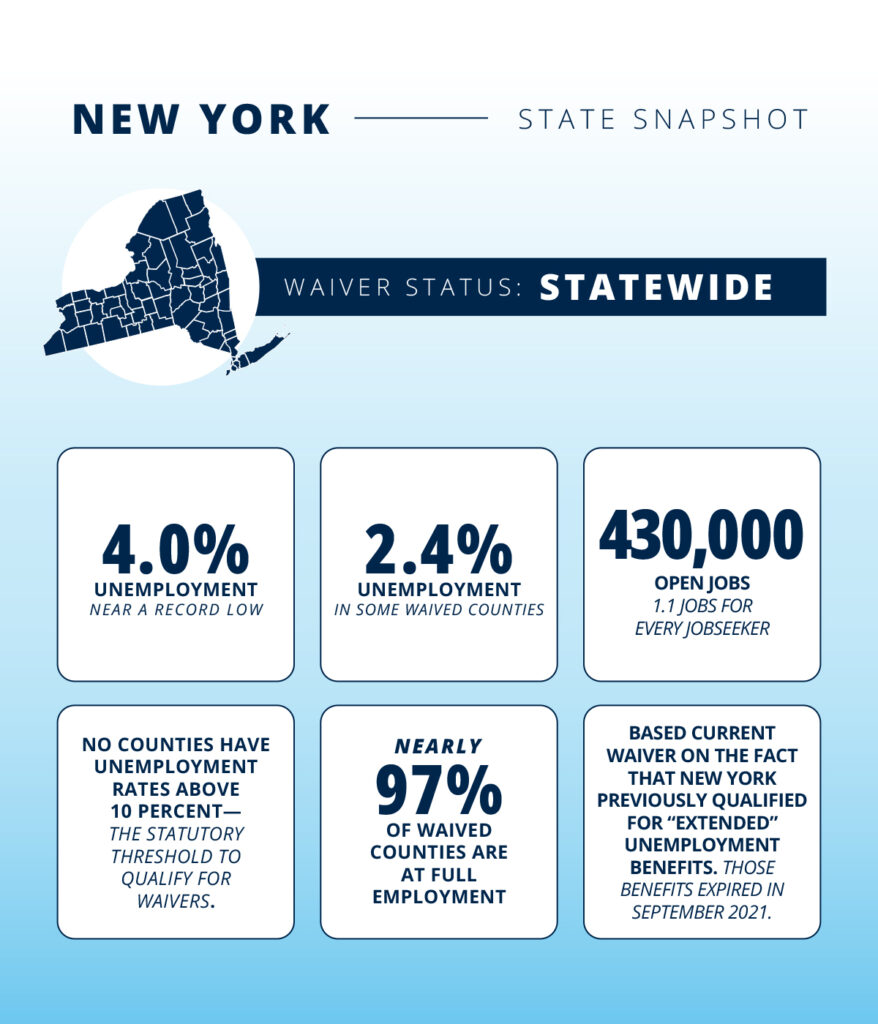

Federal regulations also give states the option to rely on the state’s eligibility for “extended” unemployment benefits to qualify for a waiver.38 But eligibility for those extended benefits— meant for periods of high unemployment—need not be recent. Not a single state currently qualifies for extended unemployment benefits and most states stopped qualifying for those benefits by the end of 2020.39 Nevertheless, most statewide waivers in effect today are based on those expired programs.40

States waive work requirements in areas with low unemployment

The food stamp statute was designed to limit waivers to areas with an unemployment rate above 10 percent, or that otherwise lacked sufficient jobs.41 But during the Clinton administration, rules were adopted that created “alternative procedures,” allowing areas to qualify for a waiver if their local unemployment rate was 20 percent higher than the national average.42 This loophole does not rely on whether an area has sufficient jobs, and rather focuses on how an area’s unemployment rate is performing when compared to the national average.43 Naturally, some areas of the country will always underperform the national unemployment rate, meaning they will always qualify for waivers, even during periods of high economic growth.44 Consider that if today’s near-record-low unemployment rate persists, states will be eligible for waivers in any areas with unemployment rates above four percent—well below the level considered full employment.45

Of the nearly 800 counties nationwide where work requirements are waived in whole or in part, just 20—less than three percent—have unemployment rates at or above the 10 percent statutory threshold.46 A whopping 75 percent of those counties have unemployment rates below what the U.S. Department of Labor defines as “full employment.”47-48

Among the states waiving the work requirement entirely—those areas deemed so economically devastated not a single able-bodied adult on food stamps could be expected to find work—have near-record amounts of open jobs—nearly 1.3 open jobs for every jobseeker in their states.49 Some waived states, such as Louisiana, have more than two open jobs for every jobseeker.50

The next horizon in waiver abuse

Faced with near-record-low unemployment levels, states have begun working with liberal advocacy groups like CBPP to prepare new ways to abuse the waiver process. This should come as no surprise, as Deputy Undersecretary Stacy Dean—who oversees the food stamp program and unilaterally and unlawfully implemented the most expensive food stamp expansion in program history—spent most of her career at CBPP urging states to use loopholes and gimmicks to bypass the work requirement and lobbying Congress to repeal the 1996 welfare reform law.51-52

In Minnesota, for example, state officials report that they work with CBPP on their waiver requests.53 In 2023, recognizing that many counties could not qualify for waivers even with numerous loopholes and gimmicks still in place, the Minnesota Department of Human Services requested waivers for specific gerrymandered groupings of ZIP Codes.54 However, the U.S. Department of Labor does not produce ZIP Code-level unemployment data.

Faced with no data to support their request, Minnesota officials simply created their own data out of thin air.55 Those bureaucrats used Census survey responses from 2016-2020 to manipulate the U.S. Department of Labor’s county-level data to justify their waiver.56

Work requirements work

When work requirements were implemented in the 1990s, millions of able-bodied adults moved from welfare to work, rapidly growing the economy.57 Analyses of state-level implementation of work requirements in food stamps have reached similar conclusions.58-63

When food stamp work requirements were implemented at the state level, able-bodied adults left welfare in record numbers.64-69 Those able-bodied adults returned to work in more than 1,000 diverse industries, touching virtually every corner of the economy.70-71 Their incomes more than doubled within a year and tripled within two years.72-76 Better still, those higher incomes more than offset lost welfare benefits, leaving them much better off financially.77-81

THE BOTTOM LINE: Congress should rein in waivers gone wild to help move millions of able-bodied adults out of dependency and off the sidelines

Commonsense work requirements can help move millions of able-bodied adults out of dependency and off the sidelines, bolstering the economy and helping fill millions of open jobs nationwide. But those work requirements are only successful when actually implemented and enforced.

States—with assistance from rogue federal bureaucrats—have used loopholes and gimmicks to bypass work requirements for more than 20 years. It is beyond time for Congress to step in and close these regulatory loopholes that violate both the letter and the spirit of the 1996 welfare reform law. Congress should simply eliminate these waivers entirely.

References

1 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Job openings and labor turnover survey: Total nonfarm job openings,” U.S. Department of Labor (2023), https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/JTS00000000JOL.

2 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the number of non-disabled, childless adults between the ages of 18 and 49 receiving food stamps between June 2020 and September 2020. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Fiscal year 2020 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program quality control database,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://snapqcdata.net/sites/default/files/2022.12/qcfy2020_st.zip.

3 Five states provided the U.S. Department of Agriculture with no data for the months of June 2020 through September 2020. For these states, the national average increase in enrollment among non-disabled, childless adults between the ages of 18 and 49 from the period between October 2019 and February 2020 to the period between June 2020 and September 2020 was applied to those five state states’ average enrollment among non-disabled, childless adults between the ages of 18 and 49 during the period between October 2019 and February 2020.

4 The U.S. Department of Agriculture uses quality control data to produce demographic characteristics reports for food stamp enrollees. Fiscal year 2020 data is the most recent available for this purpose. However, overall enrollment has changed little since this data was produced. Between June 2020 and September 2020, overall food stamp enrollment averaged nearly 42.8 million. In January 2023, the most recent month that data is available, overall food stamp enrollment remained elevated at 42.7 million. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP monthly state participation and benefit summary,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2023), https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource-files/SNAPZip69throughCurrent-4.zip.

5 7 U.S.C. § 2015(o) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021-title7.chap51-sec2015.pdf.

6 Ibid.

7 Public Law 116-127 (2020), https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ127/PLAW-116publ127.pdf.

8 7 U.S.C. § 2015(o) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021-title7.chap51-sec2015.pdf.

9 Jonathan Ingram, “Memo to FNS regarding executive order reducing poverty in America by promoting opportunity and economic mobility,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/wp.content/uploads/2018/04/Memo-to-FNS-4-10-18.pdf.

10 Jonathan Ingram and Sam Adolphsen, “Docket FNS 2018-03752,” Opportunity Solutions Project (2018), https://solutionsproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/OSP-public-comment-ANPR.pdf.

11 Sam Adolphsen et al., “Waivers gone wild: How states have exploited food stamp loopholes,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/waivers-gone-wild.

12 Sam Adolphsen et al., “Waivers gone wild: How states are still fostering dependency,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirement-waivers-gone-wild.

13 Sam Adolphsen et al., “Waivers gone wild: How states have exploited food stamp loopholes,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/waivers-gone-wild.

14 Food and Nutrition Service, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Preparing for reinstatement of the time limit for able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs),” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2021),https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource.files/SNAP%20Preparing%20for%20Reinstatement%20of%20Time%20Limit%20for%20ABAWDs.pdf.

15 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the number of ABAWDs expected to live in waived areas or otherwise utilize discretionary exemptions, as reported on fiscal year 2023 employment and training state plans.

16 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on the work status of non-disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 49 receiving food stamps between October 2019 and February 2020. See, e.g., Food and Nutrition Service, “Fiscal year 2020 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program quality control database,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2022), https://snapqcdata.net/sites/default/files/2022.12/qcfy2020_st.zip.

17 7 U.S.C. § 2015(o) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021.title7-chap51-sec2015.pdf.

18 7 C.F.R. § 273.24 (2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2022-title7-vol4/pdf/CFR-2022-title7-vol4.sec273-24.pdf.

19 Food and Nutrition Service, “Supporting requests to waive the time limit for able-bodied adults without dependents,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2021), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource.files/snap-2021-guide-supporting-abawd-time-limit-waiver-requests.pdf.

20 Office of Inspector General, “Audit report 27601-0002-31: FNS controls over SNAP benefits for able-bodied adults without dependents,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2016), https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/27601.0002-31.pdf.

21 Jonathan Ingram and Sam Adolphsen, “Docket FNS 2018-03752,” Opportunity Solutions Project (2018), https://solutionsproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/OSP-public-comment-ANPR.pdf.

22 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on Minnesota’s January 17, 2023 waiver request. Minnesota also submitted waiver requests for 16 individual, non-grouped zip-codes and nine Indian reservations.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on Oregon’s March 30, 2023 waiver approval. Oregon also received approval to waive the requirement in a second group of three counties and on eight Indian reservations.

26 Ibid.

27 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on Washington’s March 7, 2023 waiver approval. Washington also received approval to waive the requirement on two Indian reservations.

28 Ibid.

29 7 U.S.C. § 2015(o) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021.title7-chap51-sec2015.pdf.

30 7 C.F.R. § 273.24 (2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2022-title7-vol4/pdf/CFR-2022-title7-vol4.sec273-24.pdf.

31 Food and Nutrition Service, “Supporting requests to waive the time limit for able-bodied adults without dependents,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2021), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource.files/snap-2021-guide-supporting-abawd-time-limit-waiver-requests.pdf.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Authors’ review of California’s October 21, 2022 waiver approval.

35 Authors’ review of all active ABAWD waivers granted on the basis of unemployment rates 20 percent above the national average, as provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

36 Authors’ review of New Hampshire’s September 20, 2022 waiver approval.

37 The national unemployment rate sat at 14.7 percent in April 2020 during the height of pandemic-related government-imposed lockdowns, the highest level recorded since the U.S. Department of Labor began tracking unemployment in 1948. By April 2023, unemployment had reached 3.4 percent—the lowest level since 1953. See, e.g., Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor force statistics from the current population survey,” U.S. Department of Labor (2023), https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000.

38 Food and Nutrition Service, “Supporting requests to waive the time limit for able-bodied adults without dependents,” U.S. Department of Agriculture (2021), https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource.files/snap-2021-guide-supporting-abawd-time-limit-waiver-requests.pdf.

39 Employment and Training Administration, “Trigger notice no. 2023 – 18,” U.S. Department of Labor (2023), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/trigger/2023/trig_052123.html.

40 Authors’ review of all active statewide ABAWD waivers, as provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

41 7 U.S.C. § 2015(o) (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title7/pdf/USCODE-2021.title7-chap51-sec2015.pdf.

42 Sam Adolphsen et al., “Waivers gone wild: How states have exploited food stamp loopholes,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2018), https://thefga.org/research/waivers-gone-wild.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 In April 2023, the national unemployment rate sat at 3.4 percent. Areas with unemployment rates 20 percent above that threshold would be eligible for waivers. Because data for waiver requests is rounded to the first decimal, any area with an unemployment rate at or above 4.1 percent would qualify.

46 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Labor on county and county-equivalent unemployment rates in March 2023 for counties or county-equivalents with active ABAWD waivers as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The vast majority of these counties are waived in their entirety, though some states submitted waivers for specific cities, townships, zip-codes, or Indian reservations.

47 Ibid.

48 The U.S. Department of Labor defines “full employment” as “an economy in which the unemployment rate equals the nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment.” See, e.g., Kevin S. Dubina et al., “Full employment: an assumption within BLS projections,” U.S. Department of Labor (2017), https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/full-employment-an-assumption-within-bls-projections.htm.

49 Authors’ calculations based upon data provided by the U.S. Department of Labor on statewide nonfarm job openings in March 2023 and unemployment levels in March 2023 in states with statewide ABAWD waivers in effect.

50 Ibid.

51 Jonathan Ingram and Hayden Dublois, “President Biden unilaterally and unlawfully increased food stamp benefits,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2023), https://thefga.org/research/president-biden-increased.food-stamp-benefits.

52 Jonathan Ingram and Sam Adolphsen, “Dean leading FNS means we’re headed toward food stamps for all,” Inside Sources (2021), https://insidesources.com/dean-leading-fns-means-were-headed-toward-food-stamps-for-all.

53 Andrea McConnell, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Employment and training state plan FFY 2017,” Minnesota Department of Human Services (2016), https://web.archive.org/web/20220121041754/https://mn.gov/dhs/assets/MN%20SNAP%20FFY%202017%20ET% 20State%20Plan_tcm1053-298378.pdf.

54 Authors’ review of Minnesota’s January 17, 2023 waiver request, as provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid.

57 Kenneth Hanson and Karen S. Hamrick, “Moving public assistance recipients into the labor force, 1996-2000,”

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2004), https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/46832/49356_fanrr40.pdf?v=42075.

58 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “The power of work: How Kansas’ welfare reform is lifting Americans out of poverty,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2016), https://thefga.org/research/report-the-power-of.work-how-kansas-welfare-reform-is-lifting-americans-out-of-poverty.

59 Jonathan Ingram and Josh Archambault, “New report proves Maine’s welfare reforms are working,” Forbes (2016), https://forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2016/05/19/new-report-proves-maines-welfare-reforms-are-working.

60 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas.

61 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has.transformed-floridians-lives.

62 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement.

63 Jonathan Bain et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements.

64 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “The power of work: How Kansas’ welfare reform is lifting Americans out of poverty,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2016), https://thefga.org/research/report-the-power-of.work-how-kansas-welfare-reform-is-lifting-americans-out-of-poverty.

65 Jonathan Ingram and Josh Archambault, “New report proves Maine’s welfare reforms are working,” Forbes (2016), https://forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2016/05/19/new-report-proves-maines-welfare-reforms-are-working.

66 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas.

67 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has.transformed-floridians-lives.

68 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement.

69 Jonathan Bain et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements.

70 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Commonsense welfare reform has transformed Floridians’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/commonsense-welfare-reform-has.transformed-floridians-lives.

71 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement.

72 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “The power of work: How Kansas’ welfare reform is lifting Americans out of poverty,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2016), https://thefga.org/research/report-the-power-of.work-how-kansas-welfare-reform-is-lifting-americans-out-of-poverty.

73 Jonathan Ingram and Josh Archambault, “New report proves Maine’s welfare reforms are working,” Forbes (2016), https://forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2016/05/19/new-report-proves-maines-welfare-reforms-are-working.

74 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas.

75 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement.

76 Jonathan Bain et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements.

77 Jonathan Ingram and Nicholas Horton, “The power of work: How Kansas’ welfare reform is lifting Americans out of poverty,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2016), https://thefga.org/research/report-the-power-of.work-how-kansas-welfare-reform-is-lifting-americans-out-of-poverty.

78 Jonathan Ingram and Josh Archambault, “New report proves Maine’s welfare reforms are working,” Forbes (2016), https://forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2016/05/19/new-report-proves-maines-welfare-reforms-are-working.

79 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Work requirements are working in Arkansas: How commonsense welfare reform is improving Arkansans’ lives,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/work-requirements-arkansas.

80 Nicholas Horton and Jonathan Ingram, “Welfare reform is moving Mississippians back to work,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/mississippi-food-stamps-work-requirement.

81 Jonathan Bain et al., “Food stamp work requirements worked for Missourians,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/research/missouri-food-stamp-work-requirements.

82 Jonathan Ingram et al., “How the Trump administration can crack down on waivers gone wild,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/research/community-zones-reform-trump-administration.