Broken Promises: Why Expanded ObamaCare Subsidies Must Expire On Time

Key Findings

- Expanded ObamaCare subsidies are focused on a small number of high-income earners.

- Increased ObamaCare subsidy costs are helping to drive inflation.

- Extending enhanced ObamaCare subsidies will crowd out employer coverage and drive up premiums.

Overview

America’s health care system is broken thanks to little to no transparency, an astonishing lack of competition, and crippling government intervention. But excessive premium tax credits—or subsidies—under ObamaCare have made the problem even worse.

Under ObamaCare, eligible individuals can receive a taxpayer-funded subsidy that reduces the amount they pay toward premiums on the exchange.1 Prior to the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in March 2021, individuals earning between 100 and 400 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL)—or up to $111,000 in most states—were eligible for subsidies based on their income.2 Once an individual reached up to four times the poverty line, they were no longer eligible.3

ARPA fundamentally changed the ObamaCare subsidies in two major ways. First, it increased the amount of subsidies at all income lines.4 Second, it removed the four-times-the-poverty-line cap and replaced it with a new kind of cap.5 Unsurprisingly, this has dramatically expanded eligibility among those earning above four times the poverty line, all of whom were previously ineligible for subsidized coverage.6

These two changes—especially expanded eligibility—have further distorted health care prices. Unfortunately, the enhanced subsidies are focused on an extremely small portion of high-income earners at the cost of higher inflation, less employer health coverage, and more expensive health care premiums.

The expanded Obamacare subsidies must be allowed to expire as scheduled at the end of 2022.

Expanded ObamaCare subsidies are focused on a small number of high-income earners

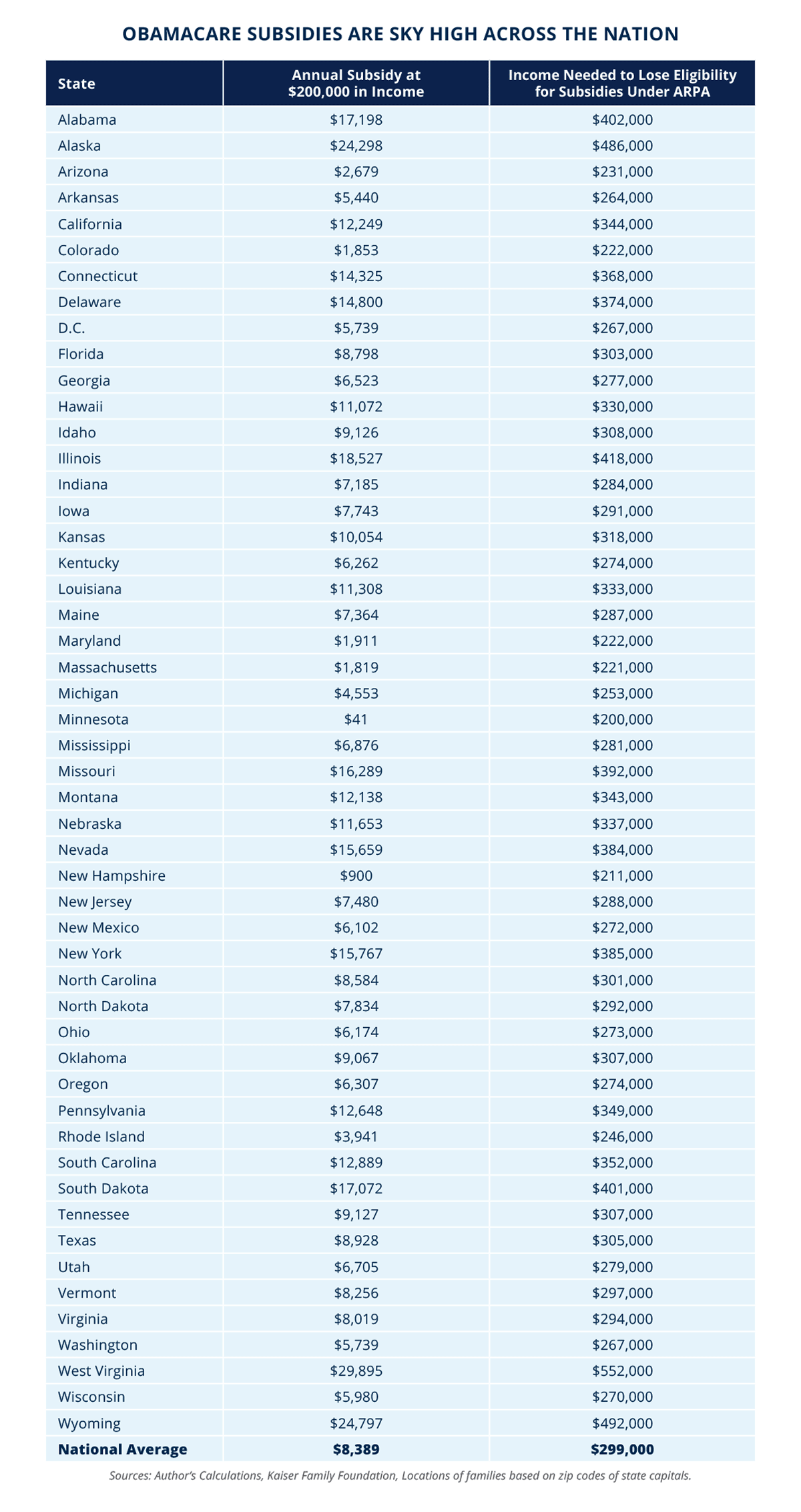

Of the estimated $30 billion that will be spent in 2022 on the ARPA-expanded portion of the ObamaCare subsidies, much will go toward a small number of Americans earning above four times the poverty line.7-8 While a typical family of four was capped out of receiving a subsidy if they earned above four times the poverty line prior to ARPA, today that same family could earn roughly 20 times the poverty line and still qualify for subsidies in certain areas of the country.9-10

For example, under the expanded subsidies, a typical family of four with two adults in their mid-50s and two teenage kids earning $200,000 per year would receive a nationwide average subsidy of nearly $8,400 for 2022.11 This number will only rise in future years as health care premiums increase.

Prior to the expansion of ObamaCare subsidies, this family would not have received a subsidy if they earned above four times the poverty line, or more than $111,000 annually in 2022.12 This same family could now be eligible for a subsidy even if they earn up to roughly $300,000 annually, on average.13 And in some areas of the country, the subsidies are even more dramatically geared towards those with high incomes.

Spotlight on West Virginia:

A family of four living in Charleston, West Virginia with two adults in their mid-50s and two kids in their teens earning $200,000 annually will receive an estimated subsidy of $30,000 in 2022—equal to roughly 15 percent of their income.14 This same family would have to earn more than $550,000—or nearly 20 times the poverty line—in order to lose eligibility for the expanded subsidies.15

Spotlight on Arizona:

A family of four living in Phoenix, Arizona earning $200,000 annually will receive an estimated subsidy of $2,679 in 2022.16 But if that same family lived in Prescott, Arizona, they would receive a subsidy of $21,120 in 2022, and would be eligible to receive subsidies until they earned $448,000 per year—equal to more than 16 times the poverty line.17

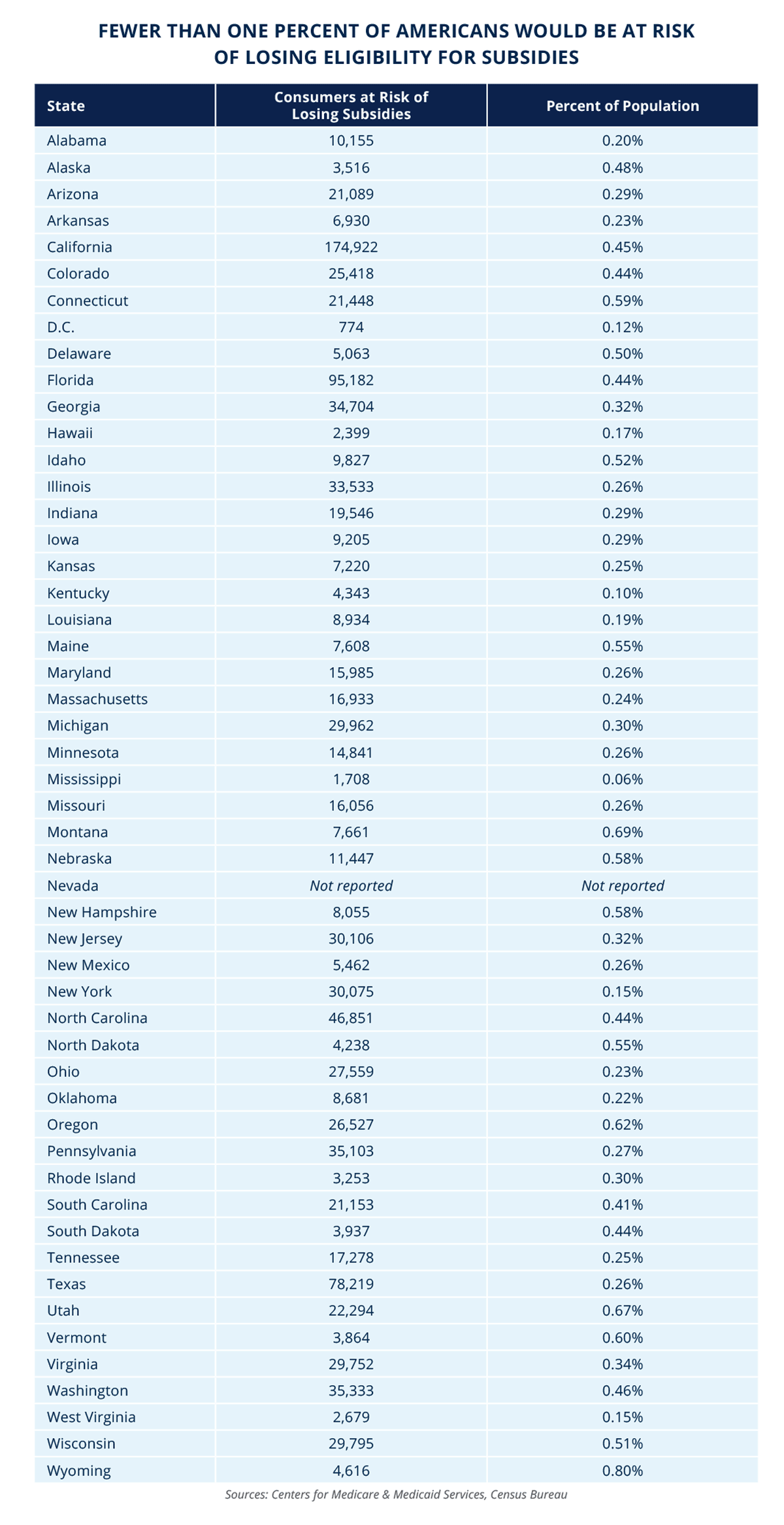

Meanwhile, just eight percent of consumers on the exchange report incomes above 400 percent FPL.18 As a result, fewer than one percent of Americans would be at risk of becoming ineligible for subsidies under the pre-ARPA framework.19-20

Increased ObamaCare subsidy costs are helping to drive inflation

The estimated 2022 cost of the expanded portion of the ObamaCare subsidies is about $30 billion, roughly 50 percent higher than the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) cost estimate from the year prior.21 This is in addition to the approximately $60 billion in traditional ObamaCare subsidies that will be spent in 2022 as well.22 The enhanced ObamaCare subsidies are contributing to deficit spending that is driving up inflation nationwide.23

The CBO estimates that permanently expanding these subsidies would increase the federal budget deficit by nearly $250 billion over the next decade.24 In fact, in 2022, ObamaCare subsidies alone will compromise roughly the same amount of spending as all federal expenditures on agriculture; science, space, and technology; and energy combined.25

Furthermore, since roughly 75 percent of the spending on the expanded subsidies is going toward individuals who already have health insurance, these subsidies simply replaced spending on insurance, causing households to divert this spending to other areas of the economy, further driving up prices.26

Extending enhanced ObamaCare subsidies will crowd out employer coverage and drive up premiums

As a result of the expanded eligibility and increased amount of ObamaCare subsidies, employers have less of an incentive to offer health benefits—since the government is now offering it for them. This temporary shortfall could quickly become permanent if the subsidies are extended, potentially resulting in more and more employers opting to rescind offering health coverage. In fact, the CBO estimates that, if extended permanently, the expanded ObamaCare subsidies would result in a 2.3 million decrease in enrollment in employment-based coverage over the next decade.27 Unfortunately, this would cause the cost of the subsidies to increase as the federal government picks up the tab.

With the government stepping in to pay for more of Americans’ health insurance premiums, insurers will face even less pressure to control costs and keep premiums down, as consumers will be even more insulated from the cost of health coverage. Ironically, rising premiums would result in even greater subsidies (since the subsidy amounts are linked to health insurance plan costs), creating a perverse cycle of ever-rising premiums and subsidies.

In fact, we’re already seeing the effects of higher premiums, with the CBO noting that premiums of exchange plans are rising more quickly than anticipated.28 Preliminary filings suggest the national average increase in health insurance premiums will be eight percent heading into 2023.29

Furthermore, because typical subsidy amounts are much greater than the tax benefits for employer health coverage, federal spending will be driven up even more as employers stop offering coverage and less expensive tax benefits are replaced by more expensive ObamaCare subsidies.31

Spotlight on West Virginia:

In 2020, the average benchmark premium for a 40-year-old was $628 per month, rising to $752 in 2022—an increase of nearly 20 percent in just two years.30 Expanded subsidies are driving premiums up by removing pressure for insurers to control costs.

THE BOTTOM LINE: The enhanced ObamaCare subsidies must expire on time.

The expanded ObamaCare subsidies are an inflationary nightmare that are driving up health care premiums for Americans while diverting billions in government benefits to a small group of individuals with six-figure incomes. To stop the cycle of higher premiums and more government spending, Congress should allow the expanded subsidies to expire on time.

1. Internal Revenue Service, “Questions and answers on the premium tax credit,” IRS (2022), https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-act/individuals-and-families/questions-and-answers-on-the-premium-tax-credit.

2. Christopher Holt and Margaret Barnhorst, “After the American Rescue Plan’s enhanced premium tax credits end,” American Action Forum (2022), https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/after-the-american-rescue-plans.enhanced-premium-tax-credits-end/.

3. Congressional Budget Office, “Reconciliation recommendations of the House Committee on Ways and Means,” CBO (2021), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-02/hwaysandmeansreconciliation.pdf.

4. Ibid.

5. Now, any individual above four times the poverty line is eligible if their premium exceeds 8.5 percent of their income. See, e.g., Congressional Budget Office, “Reconciliation recommendations of the House Committee on Ways and Means,” CBO (2021), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-02/hwaysandmeansreconciliation.pdf.

6. By definition, all individuals enrolled in exchange coverage earning more than 400 percent FPL were ineligible for subsidies prior to the passage of ARPA.

7. Brian Blase, “Fourteen reasons to let the expanded Obamacare subsidies expire,” Forbes (2022), https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2022/05/26/fourteen-reasons-to-let-the-expanded-obamacare-subsidies.expire/?sh=574316dc6cba.

8. Congressional Budget Office, “Reconciliation recommendations of the House Committee on Ways and Means,” CBO (2021), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-02/hwaysandmeansreconciliation.pdf.

9. Ibid.

10. Author’s calculations based on various scenarios calculated using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s health insurance marketplace calculator for a family of four with two adults aged 55 and two teens aged 16. See, e.g., Kaiser Family Foundation, “Health insurance marketplace calculator,” KFF (2022), https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy-calculator/.

11. Author’s calculations using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s health insurance marketplace calculator for a family of four with two adults aged 55 and two teens aged 16 using national average assumptions of plan characteristics. See, e.g., Kaiser Family Foundation, “Health insurance marketplace calculator,” KFF (2022), https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy-calculator/.

12. Congressional Budget Office, “Reconciliation recommendations of the House Committee on Ways and Means,” CBO (2021), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-02/hwaysandmeansreconciliation.pdf.

13. Author’s calculations using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s health insurance marketplace calculator for a family of four with two adults aged 55 and two teens aged 16 using national average assumptions of plan characteristics. See, e.g., Kaiser Family Foundation, “Health insurance marketplace calculator,” KFF (2022), https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy-calculator/.

14. Author’s calculations using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s health insurance marketplace calculator for a family of four with two adults aged 55 and two teens aged 16 living in Charleston, West Virginia. See, e.g., Kaiser Family Foundation, “Health insurance marketplace calculator,” KFF (2022), https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy.calculator/.

15. Ibid.

16. Author’s calculations using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s health insurance marketplace calculator for a family of four with two adults aged 55 and two teens aged 16 living in Phoenix, Arizona. See, e.g., Kaiser Family Foundation, “Health insurance marketplace calculator,” KFF (2022), https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy.calculator/.

17. Author’s calculations using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s health insurance marketplace calculator for a family of four with two adults aged 55 and two teens aged 16 living in Prescott, Arizona. See, e.g., Kaiser Family Foundation, “Health insurance marketplace calculator,” KFF (2022), https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy.calculator/.

18. Author’s calculations based on open enrollment by federal poverty line. See, e.g., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2022 marketplace open enrollment period public use files,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2022), https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-systems/marketplace-products/2022.marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

19. Author’s calculations based on the proportion of effected consumers relative to the state’s 2021 population. See, e.g., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “2022 marketplace open enrollment period public use files,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2022), https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data.systems/marketplace-products/2022-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files; and U.S. Census Bureau, “State population totals and components of change: 2020-2021,” U.S. Department of Commerce (2022), https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html.

20. These figures likely overestimate marketplace enrollment as they do not account for attrition in plan enrollment since the end of the open enrollment period.

21. Brian Blase, “Fourteen reasons to let the expanded Obamacare subsidies expire,” Forbes (2022), https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2022/05/26/fourteen-reasons-to-let-the-expanded-obamacare-subsidies.expire/?sh=574316dc6cba.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Phillip Swagel, “Health Insurance Policies,” Congressional Budget Office (2022), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-07/58313-Crapo_letter.pdf.

25. Data Lab, “Federal spending by category and agency,” USASpending.gov (2022), https://datalab.usaspending.gov/americas-finance-guide/spending/categories/.

26. Brian Blase, “Fourteen reasons to let the expanded Obamacare subsidies expire,” Forbes (2022), https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2022/05/26/fourteen-reasons-to-let-the-expanded-obamacare-subsidies.expire/?sh=574316dc6cba.

27. Phillip Swagel, “Health Insurance Policies,” Congressional Budget Office (2022), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-07/58313-Crapo_letter.pdf.

28. Congressional Budget Office, “The budget and economic outlook: 2022 to 2032,” CBO (2022), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-05/57950-Outlook.pdf.

29. Edmund Haislmaier, “Extending Enhanced ObamaCare Subsidies Would Be Costly, Ineffective,” The Heritage Foundation (2022), https://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/commentary/extending-enhanced-obamacare.subsidies-would-be-costly-ineffective.

30. Based on a 40-year-old West Virginian purchasing the average benchmark plan. See, e.g., Kaiser Family Foundation, “Marketplace average benchmark premiums,” KFF (2022), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state.indicator/marketplace-average-benchmark-premiums/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=2020-.2022&selectedRows=%7B%22states%22:%7B%22west.virginia%22:%7B%7D%7D%7D&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7.

31. Brian Blase, “Fourteen reasons to let the expanded Obamacare subsidies expire,” Forbes (2022), https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2022/05/26/fourteen-reasons-to-let-the-expanded-obamacare-subsidies.expire/?sh=574316dc6cba.