How States Can Avoid Federal Handcuffs on Unemployment Reform

KEY FINDINGS

THE BOTTOM LINE:

STATES WISHING TO USE THE NEW FEDERAL FUNDING TO SHORE UP THEIR UNEMPLOYMENT TRUST FUNDS SHOULD DO SO BEFORE APRIL 1, 2022.

Overview

Under the guise of COVID-19, Congress fundamentally changed the nature of the unemployment insurance system, transforming it to more closely mirror welfare programs.1 By providing weekly bonuses, suspending work search requirements, and extending the duration of benefits, the federal government made it more lucrative to stay home than return to work.2 These federal policy changes stifled economic recovery and wreaked havoc on unemployment trust funds, leaving many states in dire straits.3

In January 2020, states’ unemployment trust funds had more than $74 billion in assets.4 By November 2021, those trust funds had been completely wiped out and were more than $9 billion in the red.5 But some states weathered the pandemic better than others. States that indexed unemployment benefits to economic conditions fared far better than non-reform states.6

North Carolina, for example, tied its unemployment benefits to economic conditions in the aftermath of the Great Recession.7 This policy gives unemployed workers more time to find suitable work when unemployment is high and less time when unemployment is low and jobs are plentiful.8 While other states saw their trust funds go insolvent during the pandemic, North Carolina’s trust fund dropped by slightly more than 20 percent.9 The state’s trust fund assets remain above $3 billion—making it one of the largest unemployment trust funds in the nation with enough resources to cover another economic downturn if one were to occur.10 Other states that have implemented this policy have seen similar successes.11-14

But the Biden administration is seeking to handcuff states’ ability to reform their unemployment programs through a US. Department of the Treasury rule that takes effect on April 1, 2022.15 States wishing to use available federal money to replenish their trust funds should deposit or appropriate the funds before April 1 and continue to reform their unemployment programs after President Biden’s rule goes into effect.

The Biden administration is attempting to handcuff states

In 2021, Congress enacted President Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act.16 That package included $362 billion in additional federal funding for state and local governments to use for “fiscal recovery” from the COVID-19 pandemic.17 States may use these federal funds in a variety of ways, including to help replenish unemployment trust funds or repay federal loans used to pay out unemployment benefits during the pandemic.18

But in January 2022, the Biden administration finalized new regulations that attempted to block states from reforming their unemployment systems if they use the new federal funding to help shore up their unemployment trust funds.19

Under the final rule, states may not make changes to their unemployment systems that would reduce either the amount or duration of benefits for individuals on the program—such as by indexing maximum duration to economic conditions—if they deposit these federal funds into their unemployment trust funds.20 These restrictions, designed to handcuff states from reforming their unemployment systems, would remain in force until at least December 2024.21

But states are not subject to these restrictions if they act before the rule goes into effect on April 1, 2022. Importantly, states may deposit or appropriate the federal funds before the rule takes effect and continue to reform their unemployment programs after April 1.

States should deposit or appropriate the federal funds before April 1, 2022

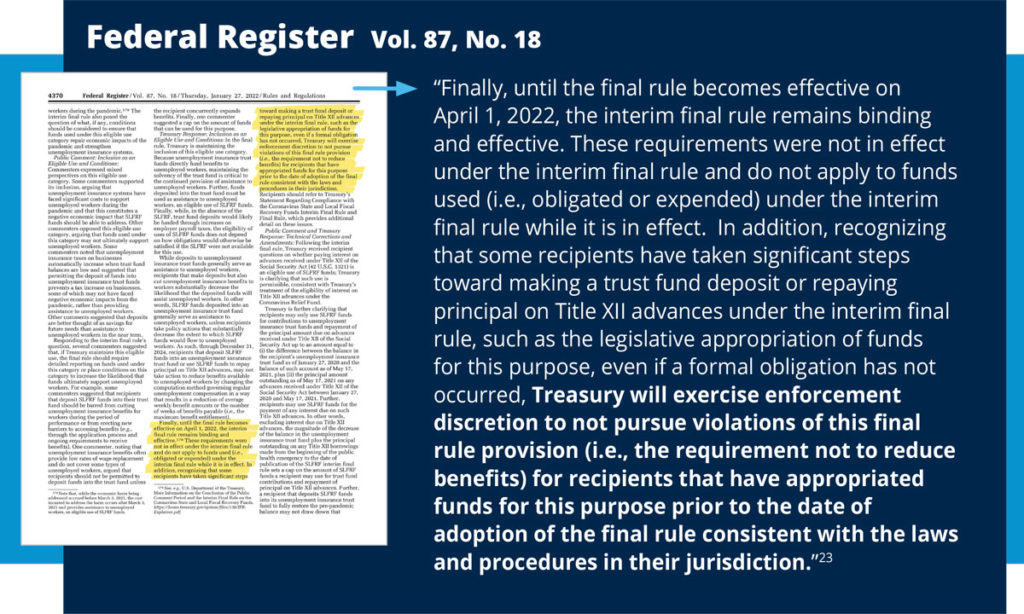

Although the rule attempts to handcuff states, the U.S. Department of the Treasury explicitly stated that these new restrictions only apply to states appropriating new federal funds after the new regulations become effective on April 1, 2022.22

Treasury was unequivocal in its commitment to not penalize states before the rule takes effect:

The final regulations make clear that states that deposit the new federal funding for their unemployment trust funds before April 1 are under no such restrictions and may reform their unemployment systems as they wish.24 The U.S. Department of the Treasury has also committed that it will not attempt to enforce these provisions against states that have not deposited the funding into their trust funds, so long as they appropriate funding for those purposes before April 1.25

If policymakers are going to use this new federal funding to help shore up unemployment trust funds, they should ensure that they deposit or appropriate the funding prior to April 1.

Bottom line: States wishing to use the new federal funding to shore up their unemployment trust funds should do so before April 1, 2022.

Federal lawmakers radically expanded unemployment during the COVID-19 pandemic, creating a cycle of benefits that largely mimicked welfare.26 Tying unemployment benefits to economic conditions is a proven way for states to replenish depleted unemployment trust funds, reduce taxes on small businesses, and move people back to work as quickly as possible.27 Indexing unemployment benefits can also better prepare states for the next economic downturn.28

Although the Biden administration is attempting to handcuff states to prevent these commonsense reforms, lawmakers have no reason to fear federal action. New restrictions on unemployment reform only apply to states who accept new federal “fiscal recovery” funding after April 1. States that deposit or appropriate those funds before April 1 are not subject to those restrictions and are at no risk of the Biden administration attempting to claw back that funding.29 Policymakers that wish to use the “fiscal recovery” funding for that purpose should ensure an appropriation is adopted prior to the April 1 deadline and continue to reform their unemployment programs after the deadline.

REFERENCES

1 Alli Fick, “How unemployment benefits have become the new welfare—And how to fix it,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/unemployment-benefits-the-new-welfare.

2 Jonathan Ingram and Hayden Dublois, “Paid to stay home: How the $300 weekly unemployment bonus and other benefits are stifling the economic recovery,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/unemployment-bonus-stifling-economic-recovery.

3 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “How indexing unemployment can restore state trust funds, cut taxes, and grow the workforce in the wake of COVID-19,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/indexing-unemployment-in-the-wake-of-covid19.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “How North Carolina has led the nation with unemployment indexing,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2022), https://thefga.org/paper/north-carolina-led-the-nation-withunemployment-indexing.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Victoria Eardley and Jonathan Ingram, “Opening opportunity: Tying unemployment benefits to economic conditions,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2019), https://thefga.org/paper/indexing-unemploymentbenefits-economic-conditions.

12 Victoria Eardley and Jonathan Ingram, “Unemployment insurance reform has strengthened Florida’s economy,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2020), https://thefga.org/paper/florida-unemployment-insurancereform.

13 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “How indexing unemployment can restore state trust funds, cut taxes, and grow the workforce in the wake of COVID-19,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/indexing-unemployment-in-the-wake-of-covid19.

14 Jonathan Ingram, “How to break the vicious unemployment circle,” Wall Street Journal (2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/break-the-vicious-unemployment-circle-florida-rate-benefits-north-carolinaalabama-index-covid-labor-11641400623.

15 Office of Recovery Programs, “Coronavirus state and local fiscal recovery funds,” U.S. Department of the Treasury (2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-01-27/pdf/2022-00292.pdf.

16 Congressional Budget Office, “The budgetary effects of major laws enacted in response to the 2020–2021 coronavirus pandemic, December 2020 and March 2021,” Congressional Budget Office (2021), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-09/57343-Pandemic.pdf.

17 Ibid.

18 Office of Recovery Programs, “Coronavirus state and local fiscal recovery funds,” U.S. Department of the Treasury (2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-01-27/pdf/2022-00292.pdf.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Alli Fick, “How unemployment benefits have become the new welfare – and how to fix it,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/unemployment-benefits-the-new-welfare.

27 Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “How indexing unemployment can restore state trust funds, cut taxes, and grow the workforce in the wake of COVID-19,” Foundation for Government Accountability (2021), https://thefga.org/paper/indexing-unemployment-in-the-wake-of-covid19.

28 See, e.g., Hayden Dublois and Jonathan Ingram, “How North Carolina has led the nation with unemployment indexing,” Foundation for Government Accountability,” (2022), https://thefga.org/paper/north-carolina-led-thenation-with-unemployment-indexing.

29 Office of Recovery Programs, “Coronavirus state and local fiscal recovery funds,” U.S. Department of the Treasury (2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-01-27/pdf/2022-00292.pdf.